India: A History. Revised and Updated (48 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

Several Mongol incursions were indeed frustrated, but in 1260 Balban fêted an embassy from Hulagu, grandson of Ghenghiz Khan. Despite Balban’s boast that up to fifteen ex-rulers of Turkestan, Khorasan, Iran and Iraq were enjoying asylum in Delhi, some sort of working relationship seems to have been established between the two neighbours. Balban could now concentrate on shoring up the status of the sultanate and securing his existing possessions. Perhaps influenced by all those royal refugees from the north-west, he introduced into his court an elaborate system of precedence and protocol modelled on Persian practice. The sultan being ‘the shadow of God’ and his vice-regent on earth, it was fitting that he be honoured as such. With drawn swords fearsome retainers now constantly attended the royal presence. Those who would approach the throne must abase themselves, performing

zaminbos

(‘kissing the ground’) and

paibos

(‘kissing the [royal] feet’) as they advanced. Any infringement of this rigid decorum brought instant and bloody punishment.

With an equally heavy hand, Balban’s forces put down insurrections in the Ganga-Jamuna Doab and cleared the region round Delhi of both the marauding Mewatis and the scrub jungle in which they found sanctuary. A major expedition into Bengal, whose governor was again in revolt, took three years and was distinguished by more ferocious reprisals. But on the sultan’s return, his most capable son and preferred successor was killed in

a skirmish with the Mongols. Balban, now said to have been in his eighties, never recovered from this blow. When not presiding, grim-faced, over his terrified courtiers, he is said to have spent his nights howling with grief for the ‘martyr-prince’. In 1287 death brought relief to the tortured sultan. Not, however, to his kingdom, which plunged into another bloodstained succession crisis.

A grandson, who quickly replaced the one Balban had nominated as his successor, celebrated his succession by renouncing the austerities of the previous reign and embarking on a riot of indulgence. The young sultan, says Ferishta, ‘delighted in love and in the soft society of silver-bodied damsels with musky tresses’. Delhi welcomed the change; ‘every shade was filled with ladies of pleasure and every street rung with music and mirth.’

20

But such was the young sultan’s abandon, such the heavy inebriants and the musky tresses, that within three years the handsome and affable prince was reduced to a gibbering wreck. Meanwhile Balban’s trusty lieutenants had been eliminated by the new sultan’s self-appointed keeper, an evil genius who was himself then poisoned by jealous opponents. ‘What little order had been maintained in the government was now entirely lost,’ according to Ziau-ud-din Barani, the author of an important history, who was a boy about Delhi at the time. The still young but now paralysed and imbecilic sultan was replaced by his son, a three-year-old toddler. In his name cradle-snatching rivals continued to manoeuvre and fight for office.

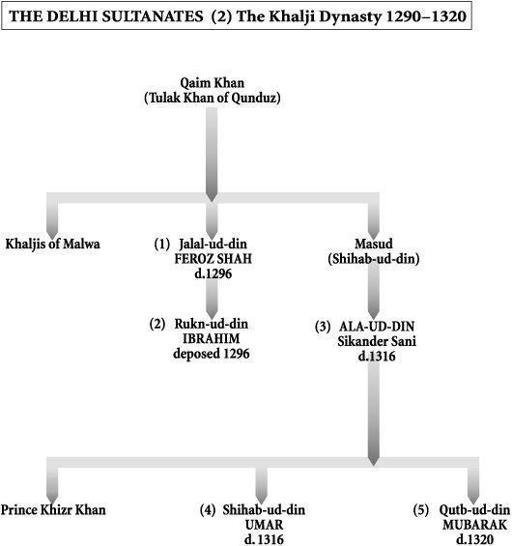

The dénouement of this 1290 crisis saw the remnants of the Turkish ‘Forty’ outwitted by rivals belonging to the same Khalji tribe who had earlier conquered Bihar and Bengal. Despatching two sultans in quick succession – both the paralytic father and his wretched child – the Khaljis ended the so-called ‘Slave dynasty’ and proclaimed one of their seniors, Jalal-ud-din Feroz Khalji, as the new sultan. A kicking toddler was thus replaced by a grey-bearded patriarch as the Khalji dynasty began its thirty-year tenure of the throne of Delhi.

Jalal-ud-din Feroz, sometimes called Feroz Shah I, was an unlikely instrument of revolution. A Turk, though not exactly a young one, he also displayed a clemency unheard of in the annals of the sultanate. It even won him a certain popularity. Conciliating rivals and forgiving enemies, he ‘weaned the citizens of Delhi from their attachment to the old family’, says Ferishta. Such policies melted even Mongol hearts. The trickle of defectors from the Mongol khanates who were embracing Islam and transferring their loyalties to the sultanate briefly became a flood. But such leniency also severely tested the loyalties of his Khalji supporters and offered much encouragement to potential opponents. Amongst the latter was the sultan’s nephew, who was also his son-in-law and a keen student of the earlier Khalji campaigns in Bengal.

This man was Ala-ud-din Khalji, and the lesson he drew from his kinsmen’s experiences in Bengal was that plunder and conquests made at the expense of Hindu India could significantly enhance his challenge for the sultanate. After a lull of nearly a century during which the tide of ‘Muslim conquest’ in India had if anything receded, another giant surge was about to carry it deep into the peninsula.

ALADDIN’S CAVE

By now, the end of the thirteenth century, the still-Hindu Deccan and south had witnessed further dynastic change. Yet the pattern of struggle, modelled on the symmetry of the

mandala

and consummated in the compass-boxing

digvijaya

, remained the same. So too does our limited perception of it. Unenlivened by the gossipy narratives beloved of Muslim writers, the contemporary history of Hindu India has still to be laboriously extrapolated from the sterile phrasing and optimistic listings favoured by royal panegyrists and fortuitously preserved in a few literary compositions and numerous stone and copper-plate inscriptions. The formality of such sources drains their content of vitality and, without the labours lavished by the likes of Tod on the rajputs, the history of the Deccan is liable to appear as arid and confusing as its geography.

Lest this should prove to be the case, it must suffice to note that in the western Deccan the Western Chalukyas, those doughty opponents of the great Cholas of Tanjore, had succumbed, like their Rashtrakuta predecessors, to the rising power of two erstwhile feudatories, one of which now dominated Karnataka and the other Maharashtra. As Yadavas, both these new dynasties claimed descent from the Vedic Yadu lineage, once of Mathura and of Dwarka in Saurashtra. They were not ‘Rajpoots’ in the geographically-specific sense used by Tod, and not certainly even

ksatriya

, a caste that is practically unknown in peninsular India. Yet as befitted a lineage that could claim Lord Krishna as a Yadava, they too revered the martial ethic.

Of these two Yadava dynasties, the Hoysalas of Halebid are the more epigraphically articulate. Originally a hill-people from the Western Ghats just north of Coorg, they had carved out a small kingdom around Belur (two hundred kilometres west of modern Bangalore in southern Karnataka) in the tenth century. In the eleventh, as ‘the rod in the right hand of the Chalukya king’, Hoysala forces had served with distinction against both the Chola kings Rajaraja and Rajendra and against King Bhoj’s Paramara successor in Malwa. More territory had been acquired, more scholars and adventurers attracted to the Hoysala court and, with the establishment of a new capital at Dorasamudra (now Halebid), twelve kilometres from Belur, the usual clustering of dynastic sites was under way. ‘Striking hostile princes in a brilliant way as if they were balls in a game,’ says an eleventh-century panegyrist (who must by now have been reborn as a cricket commentator), ‘that famous [King] Vinayaditya ruled like Indra from the west as far as Talakad, until the circle of the Earth cried out “Well done, Sir!” in approval.’

21

Imperial ambitions had first been entertained by the Hoysalas in the early twelfth century when the spectacularly ornate temples of Chenna Kesava at Belur and of Hoysalesvara at Dorasamudra-Halebid were designed to celebrate it. This bid for supremacy throughout Karnataka proved premature, but towards the end of the century, at about the same time as Prithviraj was succumbing to Muhammad of Ghor at Tarain, the Hoysalas successfully exploited a do-or-die struggle between the Western Chalukyas and the invading Kalachuris of Madhya Pradesh. Ballala II, the greatest of the Hoysala kings, thus added to his ancestral domains most of northern Karnataka and, by exploiting a similar conflict between the Chola and Pandya rulers in the Tamil country, also emerged with an important slice of the Kaveri plain around Srirangam (Trichy). A new chronological era was adopted by Ballala’s royal bards, and so were the usual imperial titles, plus many besides. Gloriously if briefly the Hoysalas were paramount throughout most of the Kannadaspeaking Deccan, and could pose as arbiters in the lusher lands below the Eastern Ghats.

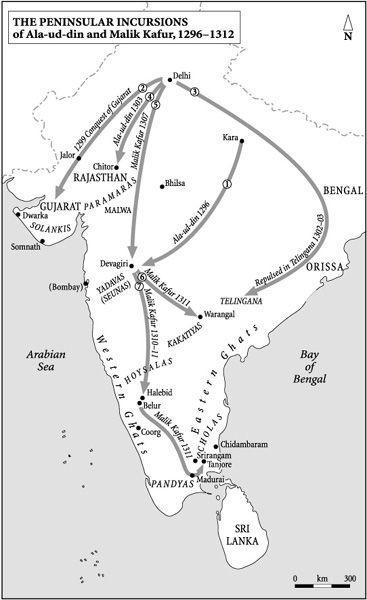

There, in the Tamil country, their main rivals were the Pandyas of Madurai who in the 1250s under the great Sundara Pandya overthrew the Cholas and blunted the Hoysala thrust. The Pandyas also struck north deep into the Telugu-speaking Andhra country, where an important dynasty called the Kakatiyas had replaced the Eastern Chalukyas of Vengi. Thus it was the Pandyas from Madurai, the Hoysalas of Karnataka and these Kakatiyas of Warangal (their capital, near the later Hyderabad), together with their respective feudatories, who controlled most of the south when, as the thirteenth century drew to a close, Ala-ud-din Khalji began to formulate his plans.

North of the Hoysalas, and barring any access to the south via the western Deccan, there ruled those other beneficiaries of the Chalukyan decline who also claimed Yadava descent. Indeed they are often referred to as the ‘Yadavas of Devagiri’. Since Maharashtra was their homeland they are also described as Marathas, although the correct name of the dynasty is Seuna, or Sevuna. These Seunas, then, once feudatories of the Rashtrakutas and then of the Chalukyas, had taken the latter’s capital of Kalyana in c1190. Although boxed in on all sides – by the Hoysalas to the south, the Kakatiyas to the east, the Paramara rajputs of Malwa in the north and the Solanki rajputs of Gujarat in the west – they had yet carved out a substantial kingdom embracing most of what is now the state of Maharashtra. Very roughly, the Seuna kingdom therefore corresponded to the territory of the ancient Shatavahanas and the early Rashtrakutas.

Beset by so many aggressive neighbours, the Seunas had taken the sensible precaution of locating their capital at the base of the most impregnable citadel in western India. A fang of rock, mostly bare of vegetation, vertiginous, accessible only by a labyrinth of caves and shafts, and further strengthened by glowering fortifications plus a Stygian moat, the citadel rises three hundred metres above the plains at a place called Devagiri (Deogir), later Daulatabad, between the rock-city of Ellora and the gardencity of Aurangabad. Here the considerable fortune amassed by the Seunas from revenue, raiding and trade seemed secure. From his eyrie King Rama-chandra could survey the core of his kingdom on the upper Godavari river safe in the knowledge that, however his armies fared, his person and possessions were unlikely to be jeopardised.

In 1296 a dry-season offensive against the Hoysalas in Karnataka was being conducted by his son. Devagiri was therefore sparsely defended. But Rama-chandra, nearing the end of a successful reign that had already lasted twenty-five years, was not unduly anxious. A few Muslim troops were already serving as mercenaries in the Deccan. The rigidity of Islam was familiar from centuries of contact, and the aggressive forays of the Delhi sultans north of the Narmada must long have been matter for comment. Three years previously the young Ala-ud-din Khalji had led a plundering expedition from his base at Kara, near Allahabad, and pushed as far south as Bhilsa, near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh. High-value booty had been secured from this ancient capital and from the neighbouring Buddhist centre of Sanchi. But Bhilsa was not halfway from the Ganga to the Godavari; there were still over three hundred kilometres of the ruggedest country between it and Devagiri. To Rama-chandra such barely authorised escapades by some unknown nephew of the remote and unusually pacific Feroz Shah I were scarcely cause for alarm. He was therefore taken completely by surprise when in the spring of 1296 Ala-ud-din suddenly materialised on his precipitous doorstep.

In the event, Rama-chandra was not the only one surprised. Ala-ud-din’s eruption into the Deccan had been kept secret even from his uncle the sultan. In fact, surprising the latter was the higher priority; for as would soon appear, the real target was not Devagiri but Delhi. Ala-ud-din was acting without authority and with comparatively few troops. From Kara via Bhilsa he had stumbled on a secluded route to the rich kingdoms of the Deccan which avoided the still-defiant rajputs of Rajasthan and Malwa. But he needed to complete his mission before it was discovered and countermanded. Speed of movement was therefore essential; he had avoided towns, camping in the jungle and following previously reconnoitred routes. On what was essentially a quest for wealth and prestige, all that mattered

was securing a quick submission plus a monumental ransom from the luckless Rama-chandra.