India: A History. Revised and Updated (47 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

Given that the Muslim conquest of India took several centuries, all generalisations must be suspect. The well-authenticated oppression of Muhammad bin Tughluq in the mid-fourteenth century cannot simply be presumed of his predecessors or his successors. Similarly a Hindu inscription of c1280 which lauds the security and bounty enjoyed under the rule of Sultan Balban should not be taken as a blanket endorsement of firm Islamic government. Not all temples were destroyed, although many were. The

jizya

tax on non-Muslims was not levied on brahmans until the reign of Feroz Shah Tughluq (1351–88),

12

and may never have been very effectively collected. Idolatry was condemned yet Hindus were not prevented from practising their religion. And since the records often make no clear distinction between military and civilian casualties, it is hard to assess the extent of gratuitous violence.

Many would argue that the sultans, like other Indian dynasts, were more interested in power and plunder than in religion. Muslim chroniclers chose to portray the occupation of northern India as a religious offensive and to paint its principals as religious heroes; ‘but such a view cannot stand the test of historical scrutiny’.

13

The more informative chroniclers in fact say surprisingly little about Muslim–Hindu relations. They are much more revealing about the power struggles amongst the conquistadors themselves; indeed these feuds, together with the chaos induced by the Mongol invasions, look to have slowed the pace of conquest quite as much as any resurgence of Hindu resistance. According to one authority the entire history of the ruling Turkish elite ‘can be summed up in these words;

they united to destroy their enemies and disunited to destroy themselves

’.

14

During the twenty-six years of his reign Iltumish was almost continuously in the field, yet beyond raids into Malwa he brought little new territory within the Muslim ambit and was as often engaged against fellow Muslims as against Indian ‘idolaters’. In the west, Sind and the Panjab were in constant turmoil as Ghenghiz Khan neared and then crossed the Indus in 1222. The turmoil was caused not just by the Mongols themselves but by the tide of armies, princes, scholars and artisans from all over Turkestan, Khorasan and Afghanistan whom the Mongol invaders rolled before them. Figures are not available but it seems probable that far more Muslims entered India as refugees from the Mongol invasions than as warriors in the Ghaznavid and Ghorid armies combined.

East of Delhi Iltumish had to reconquer much of what is now Uttar Pradesh and then face Muslim rivals in Bihar and Bengal. These were the Khaljis or Khiljis, originally tribal neighbours of the Ghorids in central Afghanistan, who had followed Muhammad of Ghor to India. Muhammad Bakhtiyar, the founder of Khalji rule, had been denied lucrative office in

both Ghazni and Delhi before eventually securing what was then a frontier fief (

iqta

) near Varanasi. Thence he organised freelance raids into Bihar, one of which was rewarded with the unexpectedly easy capture of what the Khaljis thought was a fortified city. Here the inhabitants, all of whom seemed to have shaven heads, were indeed put to death and great plunder was made. Amongst the spoils were whole libraries of books but, since all the people had been killed, no one could tell what the books were about. Further investigation, however, clarified the situation. According to Minhaju-s Siraj, a distinguished scholar who after being flushed out of Afghanistan by the Mongols spent two years with the Khaljis, ‘it was then discovered that the whole fort and city was a place of study’;

15

it was in fact the famous Buddhist monastery-cum-university of Odantapuri.

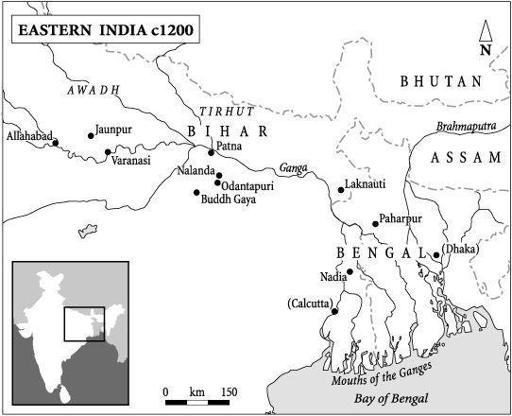

Such fearless feats of arms won the applause of Qutb-ud-din Aybak and brought followers flocking to the Khalji standard. Bakhtiyar had then ventured through south Bihar and, in another daring escapade, captured Nadia, the capital of the Senas, which dynasty had succeeded that of the Buddhist Palas as the most important in Bengal. With just eighteen followers Bakhtiyar is supposed to have gained entrance to the Sena palace and surprised King Lakshmanasena in the middle of lunch. The Senas’ other capital of Lakhnauti, otherwise Gaur on what is now the Indo– Bangladesh frontier, was also taken. With Lakhnauti as his headquarters, Bakhtiyar continued east into Assam and then ‘Tibet’ – which was probably not the country now so designated but perhaps Bhutan. Howsoever, the Himalayas were certainly too physically challenging for the Khalji forces, most of whom perished in a swollen river. Bakhtiyar made it back to the plains but, a broken man, he either died or was killed soon after.

This was in 1205, and from then onwards the governorship of Bengal and Bihar had been bitterly contested by various Khaljis who acknowledged Delhi’s supremacy only on the rare occasions when the sultan’s support was deemed personally advantageous. Iltumish endeavoured to rectify the situation by invading Bengal in 1225. Its incumbent Khalji was obliged ‘to place the yoke of servitude on the neck of submission’ and yield a hefty tribute; then he reverted to his bad old ways. A year later the sultan sent his son Nasir-ud-din to repeat the treatment. This time the Khaljis were routed, their ruler killed and their capital occupied; the problem looked to be solved. But such calculations took no account of Bengal’s notorious climate. Nasir-ud-din suddenly sickened and died. Again Bengal, that ‘hell full of good things’ as the Mughals would call it, slipped the leash and again (in 1229) Iltumish had to invade. His settlement barely lasted until

his death, whereupon Bengal, Bihar and sometimes Awadh became again effectively independent. Although over the succeeding century this situation was occasionally threatened and briefly reversed, ‘between 1338 and 1538, for long two hundred years, Bengal remained independent without interruption.’

16

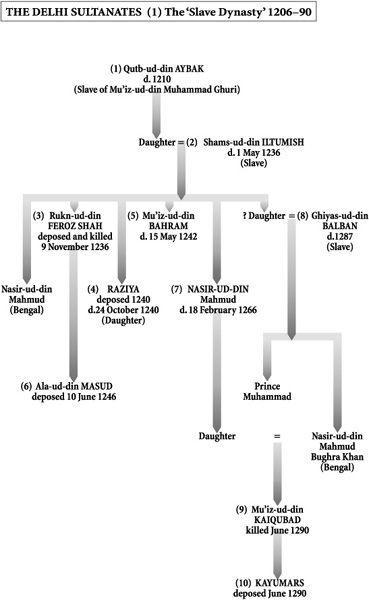

Delhi’s chances of reasserting its authority there or anywhere else declined sharply after Iltumish. Before dying of natural causes, a feat which even contemporary writers found worthy of special note, Iltumish had wavered between nominating as his successor a remaining but ineffectual son and an inspirational but gender-handicapped daughter. The son, though liked, had his own handicaps, including a vindictive and detested mother and a predilection to ‘licentiousness and debauchery’. Mother and son duly indulged their respective passions during a seven-month period. It barely qualified as a reign, and they were both then toppled by the daughter, the redoubtable Raziya.

Sultan Raziya was a great monarch. She was wise, just and generous, a benefactor to her kingdom, a dispenser of justice, the protector of her subjects, and the leader of her armies. She was endowed with all the qualities befitting a king, but she was not born of the right sex, and so in the estimation of men all these virtues were worthless. (May God have mercy on her!)

17

Nevertheless, continued Minhaju-s Siraj, ‘the country under Sultan Raziya enjoyed peace and the power of the state was manifest’; even Bengal made a grudging submission. This was short-lived, and the calm merely presaged a storm. Raziya’s reign lasted barely four years (1236–40). Perhaps her decision to dispense with the veil and, in mannish garb of coat and cap, to ‘show herself amongst the people’ was unnecessarily provocative to Muslim sensitivities. So too may have been the appointment as ‘personal attendant to her majesty’ of Jamal-ud-din Yakut, an ‘Abyssinian’ who was probably once a slave and very definitely an African. A liaison so conspicuous duly brought unfavourable comment from the historian Isami. Declaring that a woman’s place was ‘at her spinning wheel [

charkha

]’ and that high office would only derange her, he insisted that Raziya should have made ‘cotton her companion and grief her wine-cup’.

These lines, written in 1350, are of additional interest in that, according to Irfan Habib, India’s most distinguished economic historian, they contain ‘the earliest reference to the spinning wheel so far traced in India’. Since the device is known in Iran from a prior period, ‘the inference is almost inescapable that the spinning wheel came to India with the Muslims’.

18

So did the paper on which Isami penned his patronising lines, palm leaves having previously served as a somewhat friable writing surface. Both introductions were of incalculable value. Governance and taxation would be expedited, and literature, scholarship and the graphic arts revolutionised by the availability of a uniform writing material which could be readily filed and bound. In fact it became so common that by the mid-fifteenth century Delhi’s confectioners were already wrapping their sticky

halwa

in recycled writing paper, a practice which would continue until the triumph of the polythene bag and then revive after polythene’s environmental disgrace.

Likewise, the

charkha

greatly boosted the production of yarn and no doubt provided employment for many more weavers. High-quality cotton textiles had long been an important export; but thanks to the spinning wheel and other innovations, India’s cottage-based cotton industry would in time become a barometer of national self-esteem. In adopting the

charkha

as the symbol of Indian independence, Mahatma Gandhi and the Congress Party were not, however, courting Muslim votes. The irony of predominantly Hindu India sporting a national icon of Islamic provenance went unnoticed.

Raziya was elbowed aside by a junta of Turkish, and of course male, chauvinists. While bravely dashing across the Panjab in high summer to douse a revolt at Bhatinda, she was isolated by the conspirators, her Abyssinian friend was killed, and she ended a prisoner in the fort she had come to redeem. There she managed to win the backing and affection of one of the conspirators. They were married and, gathering further support, marched on Delhi. Perhaps if the conduct of their forces had been left to the experienced Raziya, they might have prevailed. But, as a wife, she deferred to her husband and they were heavily defeated. Next day, while fleeing the battlefield, the newlyweds ‘fell into the hands of Hindus and were killed’.

Known as ‘The Forty’ or ‘The Family of Forty’, the Turkish military oligarchs who now dominated Delhi affairs intrigued both against one another and against a more amorphous grouping composed of Indian converts to Islam and eminent refugees from Afghanistan and beyond. At the whim of these cut-throat godfathers young and ineffectual sultans were casually summoned and quickly despatched, usually to the hereafter.

Raziya’s demise had been followed almost immediately by another Mongol eruption. In 1241 the invaders sacked Lahore, whose ruins were then picked over by the predatory Ghakkars. Unlike Delhi, Lahore thus lost all trace of its Ghaznavid and Ghorid past and has no monuments prior to those of the Mughals. That the Mongols did not then take advantage

of Delhi’s strife-torn predicament is largely thanks to Ghiyas-ud-din Balban, another Turkish slave who, while loyally dictating policy for the ineffectual Sultan Nasir-ud-din, was briefly disgraced but, eventually and allegedly, poisoned the sultan to secure his own succession.

During forty years as the effective (1246–65) and then actual (1265–87) ruler, the stern and merciless Balban held the Mongols at bay with a skilful mixture of force and diplomacy. Ghenghiz Khan was now dead, but his successors readily championed the cause of one of Sultan Nasir-ud-din’s brothers plus other claimants to the Delhi throne; they frequently intervened in the tortuous affairs of Sind; and they advanced to the Beas river in the Panjab. This necessitated the diversion of the sultanate’s best troops and most reliable commanders to patrolling the new frontier. ‘If this anxiety … as guardian and protector of Mussulmans, were removed,’ Balban is supposed to have said, ‘I would not stay one day in my capital but would lead forth my army to capture treasures and valuables, elephants and horses, and would never allow the

Rais

and

Ranas

[i.e. the rajputs and other Hindus] to repose in quiet at a distance.’

19

While the Mongols threatened the very existence of the sultanate, even plundering raids into Hindu India, let alone conquests, were in abeyance.