India: A History. Revised and Updated (59 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

Sometimes Akbar slipped from the royal apartments to mingle unrecognised with bazaar folk and villagers. For one to whom the written word had to be read by others these contacts were a means to information and a method of verification. They were also the beginning of a lifelong enquiry into matters spiritual and religious. More obviously they made him uniquely aware of the diversity of his subjects and of the great gulf that separated them from their mainly foreign rulers. Unlike Babur or Humayun, Akbar had been born in India, in fact in an Indian village and under Hindu protection. (The place, now just in Pakistan, was Umarkot, a rajput fort in the great desert of Thar where in 1542 Humayun and his entourage had found temporary shelter during their flight from Sher Shah.) To Akbar Indians were not the uncultured mass of infidels who so horrified Babur; they were his countrymen. And whatever their religion, it was his duty not to oppress them. Discriminatory measures against Hindus, like a

tax on pilgrims and the detested

jizya

, were lifted. He would even make a point of celebrating the Hindu festivals of Divali and Dussehra.

It was also at this time, 1562, that Akbar married the daughter of the Kacchwaha rajput raja of Amber (near Jaipur, which city later Kacchwahas would build, thus becoming the maharajas of Jaipur). The marriage was partly a reward for the family’s loyalty to Humayun and partly a way of securing that loyalty to Akbar and his heirs. Additionally the raja, his son and his grandson were all inducted into the Mughal hierarchy as

amirs

(nobles), who in return for the retention of their ancestral lands, their Hindu beliefs and clan standing, would swear allegiance to the emperor and provide specified numbers of cavalry for service in the imperial forces. Both Bhagwant Das, the raja’s son, and Man Singh, his grandson, eventually became amongst the most trusted of Akbar’s lieutenants. In fact this formula, with or without a royal marriage, worked so well that it was steadily extended to numerous other rajput chiefs.

Rajasthan, so long a thicket of opposition combining the prickliest resistance with the least fruitful rewards, was thus incorporated piecemeal within the imperial system which itself became much more broad-based. In 1555 the Mughal nobility, or

omrah

, had numbered fifty-one, nearly all of them non-Indian Muslims (Turks, Afghans, Uzbeks, Persians). By 1580 the number had increased to 222, of whom nearly half were Indian, including forty-three rajputs. All benefited from this arrangement: the Mughals secured the services of a respected elite plus their warlike followers, while the rajputs gained access to high rank and wealth within a pan-Indian empire.

Not all rajput chiefs saw it that way. Some required the rougher persuasion of conquest while Udai Singh, the Sesodia Rana of Mewar, remained unpersuaded even in defeat. As a successor of Rana Sangha, Babur’s opponent at Khanua, and as the scion of the most senior rajput clan, Udai Singh was an obvious focus for dissent. He had already afforded sanctuary to Baz Bahadur, the love-lorn fugitive of Malwa, and he was openly critical of the Kacchwahas’ submission. The final straw came when Udai Singh’s son, a hostage at the Mughal court, suddenly fled south. In 1567 Akbar himself marched south and, perhaps looking for a triumph to rival that just achieved by the Deccan sultans over Vijayanagar, personally set about the siege of Chitor.

The great Sesodia stronghold, although not the most inaccessible of hill forts, was difficult to approach and had tried the ingenuity of such redoubtable commanders as Ala-ud-din Khalji and Sher Shah. For Akbar, as operations dragged on into 1568, the investment of Chitor became much more than a punitive siege. It was like a rite of passage, or a Herculean labour in which

izzat

(honour) was closely engaged. Udai Singh and his son had long since fled to sanctuary in the hills – an action so out of character for a rajput, let alone a Sesodia, that in Colonel Tod it would induce an apoplexy of indignation (‘well had it been for Mewar … had the annals never recorded the name of Oody Singh in the catalogue of her princes’

28

). Akbar pressed the siege regardless of his enemy’s absence. It became one of the great set-pieces of the age, avidly followed, gloriously recorded and in the end bloodily concluded. With flames engulfing their womenfolk, the defenders sallied forth in another suicidal

jauhar.

It was followed by Akbar’s gratuitous massacre of some twenty thousand non-combatants.

Chitor was never reoccupied. Like Vijayanagar it remains much as the sixteenth century left it. But, about a hundred kilometres to the west, in a less conspicuous setting where the Sesodias had already created a lake, Udai Singh founded a smiling new capital. He died in 1572 but in his honour the place was named Udaipur and from there the house of Mewar would continue to defy the might of the Mughals and to delight connoisseurs of rajput romance.

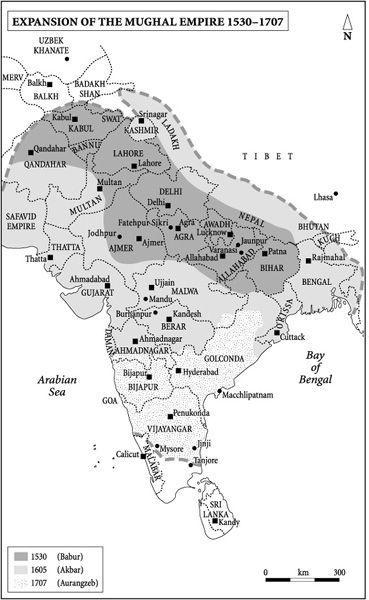

Meanwhile Akbar was also founding a new capital. Hitherto the court had been based at Agra where, lining the right bank of the Jamuna, the walls of the great Red Fort had been completed by 1562. Other fortified complexes at Lahore, Allahabad and Ajmer were underway. Together with Agra, they framed the core of Mughal empire in northern India.

29

Ajmer, now the seat of the Mughal governor for Rajasthan, had once been the capital of Prithviraj Chahamana and contained the shrine of his contemporary, the Sufi saint Muin-ud-din Chishti. To this Chishti centre Akbar made a pilgrimage by way of thanksgiving for his success at Chitor. He then sought the intercession of a living member of the Chishti community, Shaikh Salim Chishti of Sikri near Agra. For the emperor, now twenty-six, was concerned for the succession. Although not for want of brides, he was still without an heir; reassurance was needed and the shaikh obliged, correctly foretelling three sons. Akbar’s rajput bride gave birth to the first while she was lying-in at Sikri in 1569. The child was therefore named Salim (but later Jahangir) after the shaikh, the shaikh was heaped with honours, and Sikri – renamed Fatehpur Sikri – was deemed propitiously perfect as the site for a new capital.

Its construction, Akbar’s wildest extravagance and his weirdest folly, began in 1571, the same year in which the great tomb of his father was completed in Delhi. Both are regarded as classics of Mughal architecture, being artfully staged compositions, mostly in a rose-to-ruddy sandstone,

of monumental scale and majestic outline. Yet they could hardly be less alike in inspiration. Humayun’s tomb was designed by a Persian architect, who had previously worked in Bukhara. The great white-marble dome, quite unlike anything previously built in the subcontinent (although the Taj would soon make it an Indian cliché), swells from a short ‘neck’ into the billowing, bulbous hemisphere typical of Timurid Samarkand and Safavid Iran. For Humayun, the Mughal emperor most closely associated with Persia, it was wholly suitable.

For an emperor more interested in India, Fatehpur Sikri provided an equivalent opportunity. The mosque and its

Buland

(‘Lofty’) gateway apart, Akbar’s palatial complex in the middle of nowhere betrays some extravagant Persian planning but in its detail reads more like a textbook of existing Indian styles and motifs. Some had been anticipated in rajput creations like the palace of Man Singh Tomar at Gwalior. But more derive from Hindu and Jain temple architecture, especially that of Gujarat. Indeed Gujarat, won and lost by Humayun, was being reconquered and reincorporated into the Mughal empire even as the city was being built.

In an architectural setting of such blatant eclecticism Akbar’s curiosity about his subjects and their beliefs also became markedly eclectic. From patronising a few Hindu practices he launched into a thorough investigation of the whole gamut of existing religions. At Fatehpur Sikri he installed a veritable bazaar of disputing divines and presided over their heated debates with something of the relish he usually reserved for elephant fights. To the Quranic arguments of Sunni, Shia and Ismaili were added the more mystical and populist appeals of numerous Sufi orders, the

bhakti

fervour of Saiva and Vaishnava devotees, the fastidious logic of naked Jains, and the varied insights of numerous wandering ascetics, saints and other ‘insouciant recluses’.

Also welcome were representatives of several assertive new creeds. These included disciples of Kabir, the late-fifteenth-century poet and reformer, and probably those of Guru Nanak, the early-sixteenth-century founder of the Sikh faith. Kabir had spent most of his life in the vicinity of Varanasi, where he redirected the popular fervour of

bhakti

and

Sufi

devotionalism towards a supreme transcendental godhead which subsumed both Allah of Islam and brahman of Hinduism. Similar ideas of Hindu–Muslim accommodation and syncretism were explored by Guru Nanak as he travelled widely in India before eventually returning to his native Panjab, where he had once served as an accountant in the household of Daulat Khan Lodi, the two-sworded ‘blockhead’ who had opposed Babur’s progress in 1526.

Like Kabir, Guru Nanak insisted on the unity of the godhead and on

the equality of all believers regardless of community or caste.

Ulema

and brahmans alike were seen as conspiring to divide and appropriate an indivisible, infinite and unknowable God just as they divided His followers into Muslims and Hindus, Shia and Sunni, Vaishnava and Shaiva. By concentrating on this transcendent deity, on his Name and on his Word as revealed to the Guru, and by a neo-Buddhist attention to righteous conduct and truth, men might achieve the divine grace to overcome

karma

and attain salvation. Many from the trading and cultivating classes of the Panjab were drawn to this creed and formed a brotherhood (

panth

) under the nine Gurus who succeeded Nanak. To the third of these, Guru Amar Das, Akbar is said to have given the land at Amritsar on which the Sikh’s Golden Temple would eventually be built. But as yet the

panth

remained a purely religious and social movement with no political or military dimension.

Definitely included in Akbar’s theological

tournées

were Portuguese priests, of whose presence the emperor had become aware during the conquest of Gujarat. Interpreting the imperial summons as evidence of divine intervention, in 1580 the padres hastened from Goa confident of the most sensational conversion of all time. In the event they were disappointed – as were all the other disputants. Akbar’s quest for spiritual enlightenment was undoubtedly sincere but it was not disinterested. He sought a faith which would satisfy the needs of his realm as well as those of his conscience, one based on irrefutable logic, composed (like Fatehpur Sikri) of the finest elements in existing practice, and endowed with a universal appeal, something monumental and sublime which would transcend all sectarian differences and unite his chronically disparate subjects. It was a tall order and one which even a bazaar-ful of theologians could not fulfil.

In its stead, and perhaps with something of the naivety and self-reliance of the unlettered genius, Akbar improvised an ideology based on the only element in which he had complete confidence, his imperial persona. The resultant

Din Ilahi

(‘Divine Faith’) was neither clearly formulated nor vigorously promulgated. It centred on himself, but whether as God or His representative is not certain; and it graded his disciples, all of whom were senior and uncritical courtiers, according to the degree to which they could supposedly perceive his divine distinction. By Abu’l-Fazl, who became the main exponent of the new creed, this distinction was represented as a mystical effulgence which beamed from the royal forehead as from a mirror. The

Akbar-nama

devotes whole chapters to the historical pedigree of the phenomenon.

The same work begins with what looks like the standard Muslim invocation

Allahu Akbar!

(‘God is Great!’). But given the coincidence of the emperor’s name, it could also be read as the blasphemous ‘Akbar is God.’ The emperor claimed, even when the same phrase began appearing on his coinage, that no unorthodox meaning was intended. But given that he was assuming other religious prerogatives, including what some regarded as a doctrinal authority amounting to infallibility, and given the announcement of a new chronology to be known as the ‘Divine Era’ and to begin from his own accession, his disclaimer must be suspect.

It certainly seemed so to his critics. To the orthodox, to the

ulema

of whom Akbar was especially dismissive, indeed to all but royal sycophants, it looked as if Islam was under threat. Thus in 1579–80 there materialised the most serious challenge of the entire reign. Senior Islamic officials openly condemned the new directives and so provided a focus for the rebellion of mainly Afghan units in Bengal and Bihar plus a rising by Hakim, Akbar’s half-brother who held the governorship of Kabul. The latter had dynastic ambitions, the former nursed military grievances; it was not a purely religious protest. But with the promulgation in Jaunpur of a

fatwa

enjoining all Muslims to rebel, and with the naming of Hakim as the legitimate sovereign during the Friday congregational prayers, the emperor’s authority looked to be undermined.