India: A History. Revised and Updated (61 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

The system of military ranking, Akbar’s other control mechanism, assigned to every senior military commander and office-holder a numerical rank which governed his status and remuneration. Additionally a second system was introduced to denote the number of armed cavalrymen, or

sowars

, which each had to maintain for service in the imperial army; extra horses, transport and elephants were stipulated for the most senior ranks. Thus all

amirs

(nobles) and many lesser

mansabdars

(rank-holders) had both a

zat

(personal) ranking and a

sowar

(trooper) ranking. All such rankings were in the emperor’s gift, as were promotion, demotion and dismissal. The system was laden with incentives and duly produced some exceptionally able commanders and administrators. It also encouraged personal loyalty to the emperor while integrating into a single power-structure the assorted Turks, Persians, Afghans, rajputs and Indian Muslims who comprised the nobility.

Although the emperor maintained his own household troops, the recruitment and maintenance of most of his vast forces were thus in effect contracted out. Similarly, since all senior

mansabdars

were awarded

jagirs

by way of salaries, the responsibility for most revenue collection was also contracted out. Rates of remuneration, which included both the

mansabdar

’s salary and so much per

sowar

, were matched by

jagirs

affording a similar aggregate yield. If their specified yield came to more, the surplus

was due to the imperial treasury; if the

jagirdar

extracted more than the specified yield, he kept it.

‘Towards the end of [Akbar’s] reign

mansabdars

and their followers consumed 82 percent of the total annual budget of the empire for their pay allowances.’

6

There were around two thousand

mansabdars

at the time and between them they commanded 150,000–200,000 cavalrymen. The emperor personally commanded a further seven thousand crack

sowars

plus eighty thousand infantry and gunners who together accounted for another 9 percent of the budget. In addition, according to Abu’l-Fazl, the locally-based

zamindars

could muster a colossal 4.5 million retainers, mostly infantrymen. These last, who were poorly paid if at all by their

zamindars

, did not feature in the imperial budget. But by aggregating all these troop numbers and then adding to them the likely horde of non-combatant military dependants – suppliers, servants, family members – it has been suggested that the figure for those who relied on the military for a living could have been as high as twenty-six million. That would be a quarter of the entire population. The Mughal empire, whether bearing the character of ‘a patrimonial bureaucracy’ as per the administrative hierarchy, or of ‘a centralised autocracy’ as per the ranking system, was essentially a coercive military machine.

Much of this coercive potential was deployed in campaigns against obdurate neighbours like the Deccan sultanates. But, excluding those units on active service or in attendance at the royal court, many

sowar

contingents were stationed in different parts of the empire where they could be called upon to maintain order and enforce the collection of revenue. In effect many regular troops, as well as all those

zamindari

retainers, were being used to extract the agricultural surplus which financed them. It was, as Raychaudhuri puts it, ‘a vicious circle of coercion helping to maintain a machinery of coercion’.

7

Such heavy-handed intervention on the part of the central government was necessary to overcome the resistance traditionally offered by local

zamindari

interests and so maximise the revenue yield due to the emperor or his

jagirdars

. Another way of maximising the revenue yield was to improve the means by which crops were assessed and the revenue calculated. During his brief reign Sher Shah had shown the way with new land surveys, new calculations of estimated yields, and collection in cash instead of kind. But it was Raja Todar Mal, a Colbert to Akbar’s Louis XIV, who from 1560 onwards overhauled the whole revenue system. Standard weights and measurements were introduced, new revenue districts with similar soils and climate were formed, revenue officers were appointed for each such

unit, more surveys were undertaken, more data on yields and prices collected, new assessments worked out for each crop and each area, written demands issued and accepted by the village headmen, and copious records kept and filed.

The introduction of these reforms necessitated a five-year period of direct administration during which all

jagirs

were cancelled. When they were reintroduced in 1585 the results were highly satisfactory. Revenue receipts were vastly increased and the state enjoyed a massive share of rural productivity amounting to ‘one-third of all foodgrain production and perhaps one-fifth of other crops’, much of it achieved ‘at the expense of the older claims and perquisites of the

zamindars

’.

8

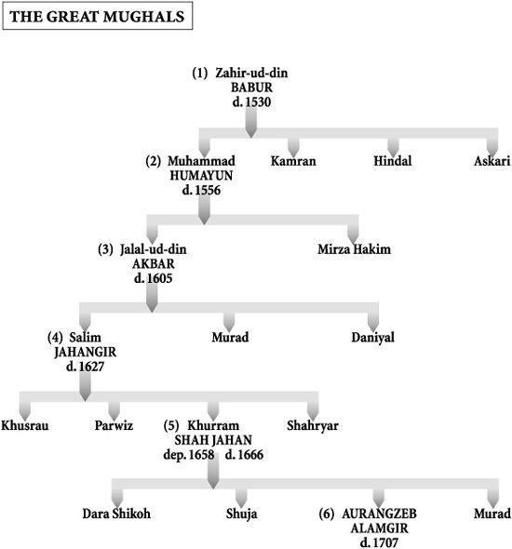

NO MAN HIS RELATION

Drawing heavily on Bernier’s account, in 1675 John Dryden’s

Aureng-Zebe

, a highly romanticised verse epic, received its first performance in London. Through such works the ‘Grand Mogul’ became synonymous in English with autocratic rule and unimaginable opulence. All foreign visitors to the India of the six Great Mughals – Babur, Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb – found ample evidence of an awesome authority and were stunned by the magnificence of the imperial setting. This last was most obviously architectural, but not exclusively. The eye-catching profusion of solid gold and chased silver, precious silks and brocades, massive jewels, priceless carpets and inlaid marbles was probably without parallel in history. Sir Thomas Roe, an emissary from James I of England and a man usually more obsessed with his own dignity, was frankly amazed when he saw Jahangir in ceremonial attire. The emperor’s belt was of gold, his buckler and sword ‘sett all over with great diamonds and rubyes’.

On his head he wore a rich turbant with a plume of herne tops, not many but long; on one syde hung a ruby unsett, as big as a walnutt; on the other syde a diamond as greate; in the middle an emeralld like a hart, [but] much bigger. His shash was wreathed about with a chaine of great pearles, rubyes and diamonds, drilld. About his neck he carried a chaine of most excellent pearle, three double (so great I never saw); at his elbowes, armletts set with diamonds; and on his wrists three rowes of several sorts.

9

Bernier was equally impressed. ‘I doubt whether any other monarch possesses more of this species of wealth [i.e. gold, silver and jewels] …,

and the enormous consumption of fine cloths of gold, and brocades, silks, embroideries, pearls, musk, amber and sweet essences is greater than can be conceived.’

Yet, despite all this show, there remained some doubt about the real prosperity of the Mughal emperors. Aurangzeb’s income, reported Bernier in the 1660s, ‘probably exceeds the joint revenues of the

Grand Seignior

[i.e. the Ottoman sultan] and of the King of Persia’. But so, continued the Frenchman, did his expenses. And although revenue receipts had doubled since Akbar’s day (partly thanks to Todar Mal’s reforms, partly as a result of the acquisition of new territories), so too had expenditure. The emperor was therefore to be considered wealthy ‘only in the sense that a treasurer is to be considered wealthy who pays with one hand the large sums which he receives with the other’.

10

As for all the gems and gold, these represented not revenue but gifts, tribute and booty, ‘the spoils of ancient princes’. Though valuable enough, they were not productive. India had long been ‘an abyss for gold and silver’, drawing to itself the world’s bullion and then nullifying its economic potential by melting and spinning the precious metals into bracelets, brocades and other ostentatious heirlooms.

There was also doubt about the size of the imperial army. Jean de Thevenot, another French visitor to Aurangzeb’s empire, had read that the emperor and his

mansabdars

could field 300,000 horse. This was what the records showed, and ‘they say indeed that he pays so many’. But,

mansabdars

being notoriously lax in providing their full complement of troopers, ‘it is certain that they hardly keep on foot one half of the men they are appointed to have; so that when the Great

Mogol

marches upon any expedition of war, his army exceeds not a hundred and fifty thousand horse, with very few foot, though he have betwixt 300,000 and 400,000 mouths in the army.’

11

Worse still, the army, like the wealth, was not always being deployed to productive effect. Akbar’s long reign (1556–1605) had been punctuated by a succession of brilliant and rewarding conquests, but as it drew to a close these were overshadowed by rivalry and rebellion. In 1600 Prince Salim, the future Jahangir, attempted to seize Agra during Akbar’s absence in the Deccan; in 1602 he actually proclaimed himself emperor; and in 1605, a few weeks before Akbar’s death, he re-erected that Ashoka pillar at Allahabad and, in a blatant assumption of Indian sovereignty, had his own genealogy inscribed alongside the Maurya’s edicts and Samudra-Gupta’s encomium. Abu’l-Fazl, by now a senior commander as well as Akbar’s memorialist, was sent to deal with the prince but was coolly murdered on the latter’s orders. Even when, after reconciliation with

his father, Salim/Jahangir’s succession seemed settled, he was opposed by sections of the nobility who preferred Prince Khusrau, his (Salim’s) eldest son. When his father was duly installed as the Emperor Jahangir (‘World-Conqueror’), Khusrau fled north, laid siege to Lahore, and had to be subdued in battle. Captured, he was eventually blinded on his father’s instructions.

‘Sovereignty does not regard the relation of father and son,’ explained Jahangir in his enlightening but decidedly naive memoir. ‘A king, it is said, should deem no man his relation.’

12

Distrust between father and son, as also between brothers, would be a recurring theme of the Mughal period, generating internal crises more serious and more costly than any external threat. Of another trouble-maker Jahangir quoted a Persian verse: ‘The wolf’s whelp will grow up a wolf, even though reared with man himself.’ This proved unintentionally apposite. In 1622 Prince Khurram, Jahangir’s second and best-loved son, on whom he had just bestowed the title ‘Shah Jahan’ (‘King of the World’), would dispose of his elder brother (the blind Khusrau) and then himself rebel against his father. The whelp was indeed worthy of the wolf. In the field or on the run, Shah Jahan led the imperial forces a merry dance for four years. Father and son were only reconciled eighteen months before Jahangir’s death in 1627. There then followed more blood-letting as Shah Jahan made good his claim to the throne by ordering the death of his one remaining brother, plus sundry cousins.

And so it went on. ‘Deeming no man their relation’, least of all their father, in due course each of Shah Jahan’s four sons would mobilise separately against him as also against one another. When Aurangzeb won this contest and in 1658 deposed his father Shah Jahan and imprisoned him in Agra’s fort for the rest of his days, he not unreasonably justified his conduct on the grounds that he was merely treating Shah Jahan as Shah Jahan had sought to treat Jahangir and as Jahangir had sought to treat Akbar. Unsurprisingly Aurangzeb would himself in turn be challenged by his progeny.

Such was the intensity of this internal strife that during much of the seventeenth century it obscured and even confounded attempts to expand Mughal rule. Jahangir’s one notable success was achieved early in his reign when Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan), at that time still ‘my dearest son’ rather than ‘the wretch’ he later became, secured the submission of the Mewar rajputs. Since Rana Udai Singh’s desertion of Chitor and its capture by Akbar, the Mewar Sesodias had recouped their forces and under Rana Amar Singh had successfully seen off several Mughal attempts to induce their submission. Khurram–Shah Jahan at the head of a vast army now concentrated on containment and attrition rather than epic sieges. There was no great battle; indeed Roe, the English ambassador, snidely remarked that the Rana had ‘rather been bought than conquered’, or ‘won to own a superior by gifts and not by arms’.

13

Nevertheless the arrival at court of the son of Rana Amar Singh was proof enough of Mewar’s shame. Jahangir, content to have succeeded where Babur and Akbar had both failed, proved magnanimous in victory, while the young Mewar prince sought to save face by excusing himself from making personal submission; no reigning Rana ever would. Amar Singh’s successors would remain on good terms with Khurram–Shah Jahan who received from them sanctuary when in revolt and support when in power.

It was during Shah Jahan’s reign as emperor and Jagat Singh’s as rana that the latter embellished his lake at Udaipur with the island, clad in white marble, which was later rebuilt as the famous Jagnivas or ‘Lake Palace’.