India: A History. Revised and Updated (65 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

To her appeal Mewar’s rana responded favourably. Welcoming the opportunity to voice Hindu opposition to the reimposed

jizya

and fearful of the iconoclasm in Marwar, he duly mobilised with strikes into Malwa and elsewhere. To resistance in Marwar (Jodhpur), Aurangzeb had thus added revolt in Mewar (Udaipur), a much more serious challenge. In 1680 a large Mughal army invaded Mewar, duly sacked the city of Udaipur and vandalised its temples. The rana, however, remained free; his forces scored some notable victories; and though peace without dishonour was eventually concluded, he maintained Mewar’s proud record of never making personal submission to the emperor.

Mughal discomfiture can be judged from the reaction of Prince Akbar, one of Aurangzeb’s sons. Akbar had commanded the Mewar campaign in its later phase but was now demoted to the Marwar command. It was not a good idea to humble an imperial contender. Inclined to the liberal views of his illustrious namesake, Prince Akbar had long been contemplating a challenge to his father. History sanctioned, indeed demanded, such conduct and rajput overtures and promises of support now emboldened him still further. In 1681 he therefore proclaimed himself emperor and marched

against Aurangzeb. The latter was at Ajmer with very few troops. It was a contest which the prince should have won handsomely. But the emperor’s adept intriguing roused the suspicions of Akbar’s rajput allies and his own dilatoriness allowed for imperial reinforcement. Without his rajput allies, and then minus most of his own troops, Akbar fled south without giving battle. Narrowly escaping capture, he reached the Deccan, there to be warmly welcomed by an even more implacable Mughal foe. Prince Akbar became a protégé of the Marathas.

Aurangzeb soon followed him. Affairs in the Deccan had been crying out for his personal intervention for the past twenty years; now into his sixties, he may reasonably have supposed that time was running out. Moreover it was from the Deccan that he himself had challenged for the throne; Prince Akbar might do the same, possibly in alliance with both Marathas and rajputs. On the other hand a final solution in the Deccan could be the crowning glory of Aurangzeb’s reign. New lands affording new sources of revenue in the form of

jagirs

were badly needed to meet the expectations of the ever-growing legion of

mansabdars

. Success in the Deccan would bring conquests to rival those of the great Akbar plus the resources to restore and sustain the imperial system which he had established.

Where the emperor went, the entire imperial court also went, plus, in this case, much of the army. The move to the south in 1681–2 meant that Shahjahanabad–Delhi was partially vacated. Like Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, Aurangzeb was shifting the whole apparatus of government to the Deccan. But this was not a move to a new capital, rather the launch of a campaign. For the purposes of travel, all moved into a tented city which was reconstituted with the same topography of bazaars, cantonments, administrative offices and imperial apartments at every halt. Once in the Deccan, they remained in camp. There they stayed, thus they lived, and thence the empire was ruled for the duration of the campaign. Akbar and Shah Jahan had campaigned in much the same style; no doubt it accorded with the semi-nomadic traditions of their Timurid-Mongol predecessors.

But what none realised was that this was a campaign without end. Many of those who went south in 1682 would never see Delhi again, including the emperor; and this was despite his having another twenty-six years to live. An active commander into his late eighties and for the most part a successful one, Aurangzeb would push Mughal rule to its greatest limits. Indeed the empire which he finally claimed exceeded that of any previous Indian ruler. But the price would far outweigh the prize. The emperor’s dogged longevity, no doubt the reward of frugal habits and pious living, would prove to be a substantial contributor to his empire’s undoing.

15

From Taj to Raj

1682–1750

‘FRAUD AND FOX-PLAY’

E

XCEPT FOR

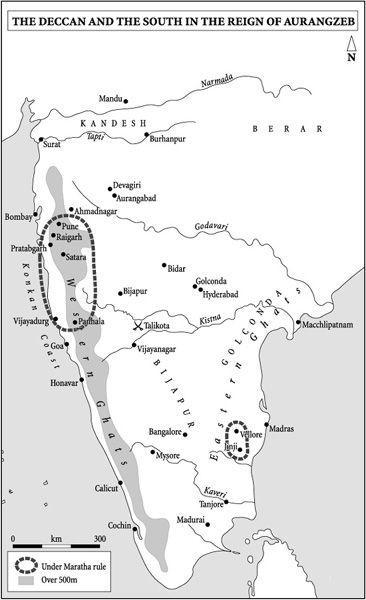

one ominous development, the Deccan to which Aurangzeb returned in 1682 differed little from the Deccan which he had left in 1658. In the north the Mughal province of that name still stretched across the upper peninsula like a waistband. Comprising the erstwhile Ahmadnagar sultanate along with the eastward territories of Kandesh and Berar, it was administered from Burhanpur in Kandesh. In the west of the province the city of Aurangabad – near the Seunas’ fang-like fortress of Devagiri (Daulatabad) and the Rashtrakutas’ cave city of Ellora – was also an important centre of Mughal power and would soon supersede Burhanpur; it had been the capital of the Ahmadnagar sultanate under ‘black-faced’ Ambar Malik but had been renamed Aurangabad during Aurangzeb’s earlier governorship.

On the coast, the Europeans came and went. From their port of Bassein the Portuguese had acquired an adjacent trickle of islands which afforded good shelter for their shipping. Amongst the coconut groves on one of the islands they had built a small fort. They called it

Bon Bahia

, or Bombay. In the 1660s, following an Anglo–Portuguese alliance against their Dutch rivals, the place was transferred to Charles II as part of his Portuguese wife’s dowry. Although Bombay itself was as yet of no commercial value, the English thus acquired a territorial toehold adjacent to the busy shipping lanes of the west coast.

To the south, Goa remained in Portuguese hands while Cochin, an important entrepôt for the spice trade, had been wrested from them by the Dutch, also in the 1660s. North of Bombay the Mughal port of Surat, superseding the now mud-silted Cambay as the main maritime outlet of northern India, hosted much the busiest Dutch and English trading establishments. From Surat European purchasing agents fanned out into the cities and weaving centres of Gujarat and beyond to place their orders and oversee despatch. And down to Surat from Ahmadabad, Burhanpur, Broach and Baroda came the bundled cottons and silks and the barrelled indigo (in great demand for dyeing uniforms) which constituted the main items of export.

On the other side of the peninsula, all three European powers, plus the newly arrived French, retained similar toeholds on the Coromandel and Andhra coasts. Textiles were again the main item of trade, but there was a tendency here for the weavers to gravitate towards the European settlements which thus became zones of export-dependent prosperity. None of these settlements was yet of much political importance but the security offered by their heavy guns and well-built forts was proving an attraction. Additionally their stocks of powder, guns and gunners were eagerly sought by the contending powers in the hinterland.

The one obvious change which had overcome the Deccan during Aurangzeb’s twenty-four-year absence was, however, momentous: whereas in the first half of the seventeenth century there had been two major powers in the peninsula, the Golconda sultanate and the Bijapur sultanate, there were now three. The Marathas had come of age. Having established their military credentials in the service of others and then, under Shivaji’s inspirational leadership, having created an independent homeland in the Western Ghats, they had since elevated the homeland into a state and Shivaji into its king.

This revival of Hindu kingship at a time of awesome and markedly orthodox Muslim supremacy had been both unexpected and highly dramatic. As well as causing a sensation at the time, Shivaji’s extraordinary exploits would transcend their immediate context to dazzle his successors, console Hindu pride during the looming years of British supremacy, and provide Indian nationalists with an inspiring example of indigenous revolt against alien rule. Latterly they have also served to encourage Hindu extremists in the belief that martial prowess is as much part of their tradition as non-violence.

Of Shivaji’s exploits the most celebrated had occurred in 1659. In the words of Khafi Khan, an unofficial chronicler of Aurangzeb’s reign, while in the north the emperor was ‘beating off the crocodiles of the ocean of self-respect’ (his brothers, in other words), Shivaji had ‘become a master of dignity and resources’. In the previous years he had captured some forty forts in the Western Ghats and along the adjacent Konkan coast. But having ‘openly and fearlessly raised the standard of revolt’, when challenged, he

revealed his true colours; ‘he resorted to fraud and fox-play’. Afzal Khan, Bijapur’s best general who had been sent to flush out ‘the designing rascal’, had run him to ground at the hill fort of Pratabgarh (near Mahabaleshwar). The Bijapuri army lacked the means to take such a strong position, while the Marathas stood no chance of driving them off. In time-honoured fashion the stalemate had therefore to be resolved by negotiation. Shivaji would have to make a token recognition of Bijapur’s suzerainty; Afzal Khan would have to leave Shivaji in undisturbed possession of his forts. This much having been agreed, it remained only for Shivaji to make his personal submission.

In a clearing at the foot of the Pratabgarh hill the two men met. Each had supposedly dispensed with attendants and weapons. Nevertheless, ‘both men came to the meeting armed’.

1

Amongst Shivaji’s hidden arsenal was a small iron finger-grip with four curving talons, each as long and as sharp as a cut-throat razor.

As soon as that experienced and perfect traitor [i.e. Shivaji] neared Afzal Khan, he threw himself at his feet weeping. When he [Afzal Khan] wanted to raise his [Shivaji’s] head and put the hand of kindness on his back to embrace him, Shivaji with perfect dexterity thrust that hidden weapon into his abdomen in such a way that he [Afzal Khan] had not even time to sigh, and thus killed him.

2

Shivaji then gave a signal to his men who were hidden in the surrounding scrub. Taking the Bijapuris by surprise, they ‘destroyed the camp of the ill-fated Afzal Khan’, captured his stores, treasure, horses and elephants, and enrolled many of his men. ‘Thus Shivaji acquired dignity and force much larger than before.’

Since some of the Bijapuri troops were actually Marathas and some of Shivaji’s were Muslims, it is clear that what Khafi Khan’s translator renders as ‘dignity’ – or perhaps ‘prestige’ – mattered more than creed. The same translator, a Muslim, calls the affair ‘one of the most notorious murders in the history of the subcontinent’; yet it seems that to contemporaries, as to most Hindu historians, it was testimony to Shivaji’s resourceful genius as much as his ‘designing turpitude’. Whilst the loyalties of kinsmen and co-religionists were vital, so were those of the assorted dissidents and adventurers who now recognised in him a leader of indomitable courage and assured fortune. Shivaji, says Khafi Khan, ‘made it a rule … not to desecrate mosques or the Book of Allah, nor to seize the women’.

3

Muslims as well as Hindus could comfortably serve under his standard.

Shivaji celebrated his success over Afzal Khan by grabbing more of the

Konkan coast between Bombay and Goa. There he assembled a small navy and began the fortification of the coves and estuaries from which it would operate. He also seized the pine-scented heights of Panhala, more a walled massif than a hill fort, just to the north of Kolhapur. A new Bijapuri army caught up with him there but, in another celebrated exploit, he gave the enemy the slip by escaping under cover of darkness with a few trusted followers.

By 1660 Aurangzeb had dealt with the ‘crocodiles’ and had sent to the Deccan a large army under Shaista Khan, the brother of Shah Jahan’s beloved Mumtaz Mahal. Shaista Khan was to secure the territories ceded to the empire by Bijapur in 1657, which included the Maratha homeland in the Ghats. Shivaji thus faced a new and much more formidable foe whom he had even less chance of defeating. The Mughal army was relentlessly harried and every fort took a heavy toll of Mughal blood; yet Pune, Shivaji’s capital, fell; then one by one the Maratha strongholds succumbed. By 1663 Shivaji was facing defeat. Another exploit was called for.

Shaista Khan had taken up residence in a house in the now Mughal city of Pune. No Marathas were allowed within the city walls and the house was heavily guarded. But special permission was obtained for a wedding party to enter the city and on the same day a more disconsolate group of Marathas were brought in as prisoners. Late that night the bridegroom, the wedding party, the prisoners and their guards met up as arranged. Discarding disguise, they produced their weapons, crawled into the compound of Shaista Khan’s house through a kitchen window, and then smashed through a wall to reach the sleeping apartments. There ‘they made everyone who was awake to sleep in death and everyone who was asleep they killed in bed.’ Shaista Khan himself was lucky. He lost a thumb and seems to have fainted, whereupon ‘his maid servants carried him from hand to hand and then took him to a safe place.’ According to Khafi Khan, whose father was serving in Pune at the time, the Marathas then mistook their man and killed someone else thinking it was the Mughal commander. Also killed was Shaista Khan’s son and one of his wives. No plunder was taken; the raiders withdrew as suddenly as they had emerged; and although Shivaji himself was not among them, it seems that he had organised the raid and had probably secured the collusion of one of the Mughal generals.