India: A History. Revised and Updated (67 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

In 1705 Aurangzeb fell seriously ill. A frail and shrouded spectre dressed ‘all over white’, as a visitor put it, with turban and beard of the same ghostly pallor, he was installed in a palanquin and carefully carried back to Ahmadnagar. Even then he was a long time dying. Embittered and isolated, he prayed hard, bemoaned the state of affairs, and found fault with his officials; he had already despaired of most of his progeny. As for himself, ‘I am,’ he wrote, ‘forlorn and destitute, and misery is my ultimate lot.’

8

The misery ended in 1707, his ninetieth year. His funeral expenses were supposedly met from the sale of the Qurans he had copied and the caps he had stitched. True to his wishes, he was buried not beneath a stylish mountain of marble and sandstone at the heart of the empire but in a simple grave beside a village shrine dear to the Muslims of the Deccan. At Khuldabad, not far from Aurangabad, a neat little mosque now flanks the small courtyard in which stands the least pretentious of all the Mughal tombs. There is barely room for a vanload of pilgrims. And instead of a great white dome, a dainty but determined tree provides the only canopy.

TOWARDS A NEW ORDER

Considering that, by one calculation, Aurangzeb was survived by seventeen sons, grandsons and great-grandsons, all of an age in 1707 to lay claim to the throne, the war of succession passed off comparatively smoothly. Not, though, cheaply. Treasure was disbursed by the bucketload,

jagirs

doled out, armies mobilised, and about ten thousand soldiers butchered in the process.

The two main contenders clashed near Agra on nearly the same battle site as had Aurangzeb and his brother Dara Shikoh. Prince Muazzam (also known as Shah Alam), previously governor in Kabul, defeated and killed Prince Azam Shah, from the Deccan, and then assumed the title of Bahadur

Shah (or Shah Alam I). Another brother of doubtful sanity entered the fray a year later and was routed and killed in 1709. The new emperor promised well, despite his years. But whereas Aurangzeb’s reign had lasted far too long for the good of his empire, Bahadur Shah’s proved far too short. He died after five years. One succession war was barely over before the next began. And in between, major crises in Rajasthan and the Panjab, plus rural unrest just about everywhere, had fatally exposed the fragility of Mughal power.

The Rajasthan problem began with the eviction of Mughal troops from Marwar (Jodhpur) by Ajit Singh, the infant who had been sneaked out of Delhi in 1678. Now nearly thirty, Ajit was taking the long-awaited opportunity of Aurangzeb’s death to avenge the earlier desecration of Marwar. Support came from other rajputs including the Kacchwahas of Amber (Jaipur) and the Sesodias of Mewar (Udaipur). But Bahadur Shah proved equal to the challenge. Overawing the Kacchwahas and ignoring the Sesodias, he re-invaded Marwar and reached a compromise settlement with Ajit Singh. A year later Ajit Singh and Jai Singh Kacchwaha again rose in revolt and attacked the provincial capital of Ajmer. Such repeated defiance would once have invited the direst of reprisals but now elicited only further clemency. As Bahadur Shah hastened away to the Panjab to deal with the Sikhs, it began to look as if imperial indulgence of the rajputs, once founded on strength and dictated by policy, was now beset by doubt and dictated by circumstance. Ten years later, after further rajput defiance and more abject Mughal concessions, the Jaipur and Udaipur rajas were said to hold ‘all the country from 30 kos [about a hundred kilometres] of Delhi, where the native land of Jai Singh begins, to the shores of the sea at Surat’.

9

The more pressing Sikh problem arose from the assassination in 1708 of Gobind Singh, the last of the Sikh Gurus. At the time the Guru had been attending the emperor in the hopes of winning back a Sikh base recently established at Anandpur Sahib (near Bilaspur in Himachal Pradesh) and of obtaining redress against the local Mughal commander who had been hounding the Sikhs. This same man, who had also murdered the Guru’s two sons, was now widely regarded as having instigated the death of the Guru himself.

By the peace-loving disciples of Guru Nanak such provocation might once have been ignored. But under Guru Gobind the Sikh

panth

(brotherhood) had undergone a radical transformation. Retreating to the Panjab hills after Aurangzeb’s execution of Guru Tegh Bahdur in 1676, Guru Gobind had been obliged to arm his followers so that they might hold their own against the hill rajas. Support arrived from Sikhs scattered

throughout north India. The claims of conscience were now to be maintained by force whenever necessary. Even Mughal contingents were successfully repulsed. In keeping with this more assertive stance, Guru Gobind had also introduced a more rigid standard of orthodoxy. True Sikhs must henceforth be inducted through a baptismal ceremony into the

khalsa

, ‘the pure’; and they must leave their hair uncut, carry arms and adopt the epithet of ‘Singh’ (‘Lion’). Clearly recognisable, more cohesive, more territorially aware, and much more militant, the

panth

was readying itself to join the contest for power in the late Mughal period.

Within a year of the Guru’s death a disciple calling himself Banda Bahadur began collecting arms and followers in the eastern Panjab. The Panjab, like other provinces, had prospered during the first half of the seventeenth century, with revenue receipts increasing by two-thirds and Lahore becoming a major commercial centre. This trend had since been reversed, with both agricultural production and revenue falling despite rising prices. Rural distress added to Banda Bahadur’s appeal and turned his protest into ‘a millennial resistance movement’

10

with a strong element of lower-caste revolt. Though poorly armed, the Sikh forces began systematically storming the mainly Muslim towns of the region.

Banda himself assumed a royal title, initiated a new calendar and began minting the first Sikh coinage. In thus adding political autonomy to the aspirations of the new brotherhood of the

khalsa

, he anticipated by nearly a century the Sikh kingdom of Ranjit Singh. Although forced to retreat into the hills by Bahadur Shah’s massive onslaught, Banda and his many sympathisers outlived the emperor and, when finally defeated in 1715, left a legacy of defiant protest and sectarian militancy. ‘Though Banda Bahadur, … and along with him seven hundred other Sikhs, were captured and slain in 1715, Sikh hostility continued to subvert the foundations of Mughal power till the province was in total disarray in the middle of the eighteenth century.’

11

Despite such chronic subsidence, the Mughal edifice would stand for another 150 years. During this period its legitimacy and authority were rarely questioned. Well into the nineteenth century even the British acknowledged Mughal supremacy and worked within its institutions. But the erosion of its wealth and power in the early decades of the eighteenth century, and the expropriation of the system through which they operated, was indeed spectacular. Traditionally this is explained in dynastic terms. Disputed successions, imbecilic contenders, and short reigns resulted in a rapid depletion of imperial resources, leading to administrative chaos and regional secession. To these ‘causes’ of the ‘decline’ of the empire, historians with

Hindu sympathies add the alienation occasioned by Aurangzeb’s religious policies, while those of Marxist sympathies emphasise rural desperation and peasant unrest as a result of the failure of an agrarian system founded on excessive exploitation and minimal investment. As so often, more historical data only generate less in the way of comforting certainty.

That local disturbances preceded Aurangzeb’s death and then became widespread throughout the empire suggests that the Sikh and rajput troubles were symptomatic of a deeper problem. But whether this resulted directly from the sort of rural oppression so graphically described by Bernier is doubtful. ‘It was not so much impoverished peasants but substantial yeomen and prosperous farmers already drawn into the Mughals’ cash and service nexus, who revolted against Delhi in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.’

12

These yeomen and farmers were otherwise the vaguely defined, immensely various but always locally-based elites known as

zamindars

, the men at whose expense Todar Mal had set up his revenue system. Thanks to favourable trading conditions and increased yields during the first half of the seventeenth century they had evidently more than recouped their losses. In the

sarkars

(districts) and

parganas

(sub-districts) of northern India there was now a general flexing of

zamindari

muscle as such local caste-and kin-based groupings used new wealth to buy their way back into the revenue system or to acquire the troops and arms with which to defend existing privileges. The imperial edifice was being insidiously undermined from below even as, above ground, it was being converted and partitioned.

This unrest, it is argued, contributed to a

jagirs

crisis. Throughout the Mughal period

mansabs

had been subject to a bounteous inflation as more and more rank-holders were given higher and higher rankings. On the other hand, the supply of the

jagirs

which were supposed to support these rankings failed to keep pace, while their individual yields actually dwindled. A scale of differentials was drawn up to address this problem, but it seems that

jagirdars

now so dreaded ending up

jagir

-less that they defied orders to transfer from their

jagirs

and began to regard them as permanent perquisites which could be leased or farmed out at will and passed on to their heirs.

Office-holders felt the same way about their offices. At the highest level this meant that provincial governorships often came to be held for life and might, in the hands of a powerful and ambitious incumbent, become heritable. By the 1730s this would indeed be the case in respect of the governorships of the Panjab, Bengal, Awadh (Oudh) and the Deccan. The short step to genuine autonomy quickly followed, usually in the form of a refusal either to remit the provincial revenue to the imperial treasury or

to attend in person at the imperial court. In Bengal and Awadh two generations served to turn the provincial governor into an autonomous nawab; in the Deccan the incumbent governor’s title of Nizam-ul-Mulk simply became analogous with ‘nawab’.

This was not, however, outright secession – more like devolution or a radical decentralisation. And in many ways the empire as represented by the sum of its parts proved more prestigious and entrenched than when all power rested with the emperor. The nawabs would continue to operate through the officers and institutions inherited from Mughal administration. Prayers continued to be said in the emperor’s name; coins continued to be struck in the emperor’s name. His person and his authority gave to the new order its only legitimacy. In effect the Mughal emperor was conforming to the traditional pre-Islamic model of a

maharajadhiraja

or

shah-in-shah.

The latter had actually become a Mughal title; ‘a king of kings’, it also signified ‘a king

among

kings’. However debilitated, the later Mughals stood unchallenged at the pinnacle of ‘a hierarchy of lesser sovereigns’, presiding over something not unlike that ancient ‘society of kings’.

A COMMUNION OF INTEREST

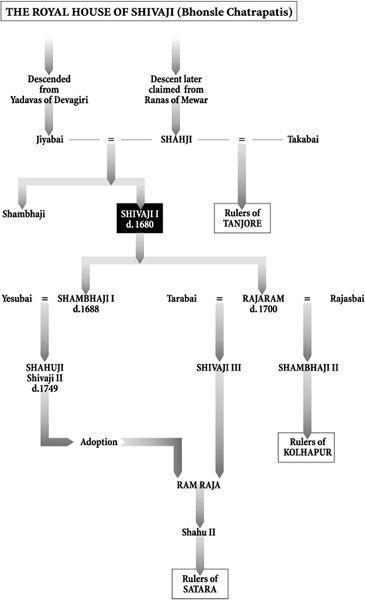

Proof that the authority of the Mughal empire remained paramount came most obviously from the willingness of even the Marathas to seek its sanction. For the Marathas the most important consequence of Aurangzeb’s death had been the release of Shahuji, son of the dismembered Shambhaji (and so grandson of Shivaji). He had been brought up in the imperial camp but had not been obliged to convert to Islam and, when freed by Bahadur Shah, boldly claimed the Maratha throne. Tarabai, his aunt, contested this in the name of her own son, Shambhaji. The still spluttering Mughal–Maratha war thus became a three-cornered affair, with Shahuji also bidding for the loyalties of the Maratha leaders. Meanwhile governors of the Mughal Deccan came and went, one favouring Shahuji and the next Tarabai. Stalemate brought only chronic anarchy, until in 1713 Shahuji began to listen to the councils of the redoubtable Balaji Vishvanath.

A brahman from the Konkan coast who had once worked as a clerk of salt-pans, Balaji lacked the more obvious credentials of a rough-riding Maratha. ‘He did not particularly excel in the accomplishment of sitting upon a horse and, at this time, required a man on each side to hold him.’

13

Nevertheless he enjoyed a great reputation for that other essential Maratha campaigning skill – negotiating. In 1714 he pulled off an unlikely coup by

winning for Shahuji the support of Kanhoji Angria, admiral of the Maratha fleet (or ‘the Angrian Pirate’ as the British in Bombay called him), who had been the mainstay of Tarabai’s faction. Balaji was rewarded with the post of Shahuji’s ‘peshwa’ or chief minister; his fellow brahmans assumed responsibility for the Maratha administration and also boosted its credit-worthiness; and Shahuji’s situation immediately began to improve. In due course the office of peshwa would become hereditary in Balaji’s family and the peshwas, rather than their royal patrons, would become the dispensers of Maratha power and patronage for the next sixty years.