India: A History. Revised and Updated (68 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

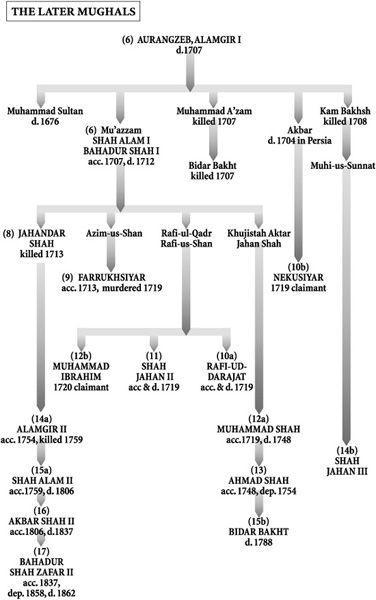

Meanwhile in Delhi the succession crisis which followed Bahadur Shah’s death in 1712 was taking its course. Although orchestrated more by senior Mughal officials than by the four contesting sons of Bahadur Shah, it proved no less costly in blood and treasure and it resulted in the accession of a man not unfairly described by Khafi Khan as a frivolous and drunken imbecile. Luckily this Jahandah Shah lasted only eleven months, a short reign if a long debauch. ‘It was a time for minstrels and singers and all the tribes of dancers and actors … Worthy, talented and learned men were driven away, and bold impudent wits and tellers of facetious anecdotes gathered round.’ The anecdotes invariably concerned Lal Kunwar (or Kumari), the emperor’s outrageous mistress, on whose fun-loving relatives were showered

jagirs

,

mansabs

, elephants and jewels. So infectious was the mood that ‘it seemed

kazis

would turn toss-pots and

muftis

become tipplers.’

14

The party ended, and decorum was temporarily restored, when in 1713 Farrukhsiyar, the son of one of Jahandah Shah’s unsuccessful brothers, approached from Bihar with a sizeable army. Jahandah Shah’s forces mostly melted away, and Farrukhsiyar, who had already declared himself emperor, began his six-year reign (1713–19). It was he who was responsible for the bloody repression of Banda Bahadur and his Sikhs, and it was he who would fatefully indulge the ambitions of the English East India Company.

But his bid for power, as now his rule, depended heavily on two very able brothers known as the Saiyids, one of whom had been governor of Allahabad and the other of Patna. The Saiyids were now rewarded with the highest offices, but soon fell out with an emperor whose ambition was exceeded only by his chronic indecision. Finding the Saiyids at first overbearing, then indispensable, then intolerable, Farrukhsiyar finally ordered the younger, Husain Ali Khan, to the Deccan. As governor of the Deccan he would be out of the way; better still, as per secret instructions given to the governor of Gujarat, he would be opposed and killed

en route

. In the event it was the Saiyid who disposed of his would-be assassin and who then, not surprisingly, began planning his revenge on the emperor.

Into this vendetta the Marathas were drawn, and it was under cover of it that their forces would finally burst out of the Deccan and Gujarat to begin their long involvement in the affairs of northern India. Whether the initiative came from the Saiyid Husain Ali Khan or from the Peshwa Balaji Vishvanath is not clear; but in 1716 negotiations were opened between these two which ostensibly aimed at ending the Mughals’ thirty-year war with the Marathas. Like Shivaji in 1665, Shahuji would have to accept Mughal rule in the Deccan, furnish forces for the imperial army and pay an annual tribute. But in return he demanded a

farman

, or imperial directive, guaranteeing him

swaraj

, or independence, in the Maratha homeland, plus rights to

chauth

and

sardeshmukh

(amounting to 35 percent of the total revenue) throughout Gujarat, Malwa, and the now six provinces of the Mughal Deccan (i.e. including the erstwhile territories of Bijapur and Golconda in Tamil Nadu). This was a very substantial demand and, although Husain Ali Khan agreed to the terms, they were flatly rejected by Emperor Farrukhsiyar, who realised that such a

farman

would effectively end Mughal power in the region.

15

Saiyid Husain Ali Khan, however, determined to press the treaty in person. His brother in Delhi was under constant threat from the intrigues of the vacillating emperor, and was urging his presence. Likewise Peshwa Balaji, in return for ratification of the treaty, was eager to support him. Accordingly, at the head of a joint army of Maratha and Mughal troops, the peshwa and the younger Saiyid headed north for Delhi in 1719.

Unopposed, they approached the city and pitched camp beside the Ashoka pillar reerected by Feroz Shah II. The sound of their drums travelled up the Jamuna – which in those days still slid below the ramparts – and could be heard in the great Red Fort of Shahjahanabad. There Farrukhsiyar was quickly isolated and, with his guard surreptitiously replaced, fell an easy prey to the Saiyids. Blinded, caged, poisoned, garrotted and eventually stabbed, his death partook of the indecision which had characterised his life. He was replaced on the throne by a consumptive youth who lasted only six months, then by the latter’s equally irrelevant brother, who rejoiced in the title of Shah Jahan II but died, says Khafi Khan, ‘of dysentery and mental disorder after a reign of three months and some days’. ‘Matters went on just as before …’, continues the chronicler, ‘he [Shah Jahan II] had no part in the government of the country.’

16

Under Saiyid scrutiny the first of these imperial nonentities did, however, sanction the Maratha treaty. Balaji Vishvanath and his men returned to the Deccan well pleased with their work.

Meanwhile Muhammad Shah, the third emperor in a year, was installed by the Saiyids. In an unexpectedly long reign (1719–48), his most notable

achievement came early when in 1720 the younger Saiyid was murdered and the older defeated. But having freed himself of his minders, the emperor promptly fell a prey to other warring factions and seemingly despaired of actually ruling. ‘Young, handsome and fond of all kinds of pleasures, he addicted himself to an inactive life.’

17

Catastrophic raids on Delhi by the Marathas (1737), by Nadir Shah of Persia (1739) and by the Afghan Ahmad Shah Abdali (1748 onwards) would fail to galvanise him. His reign, though long, would not be glorious.

Meanwhile Peshwa Balaji Vishvanath, the Saiyids’ ally, had also died in 1720. His son, Baji Rao I, ‘after Shivaji the most charismatic and dynamic leader in Maratha history’,

18

duly inherited the office of peshwa. He also inherited the dazzling prospect opened by the new treaty plus his father’s understandable contempt for the might, if not the mystique, of the Mughal emperor. Over the next two decades the Marathas would raid north, south, east and west with impunity. They reached Rajasthan in 1735, Delhi in 1737 and Orissa and Bengal by 1740. But the loose structure of Maratha sovereignty remained. Balaji’s distribution of the ceded Deccan revenues amongst various Maratha commanders had produced what James Grant Duff, the first historian of the Marathas, called ‘a communion of interest’.

19

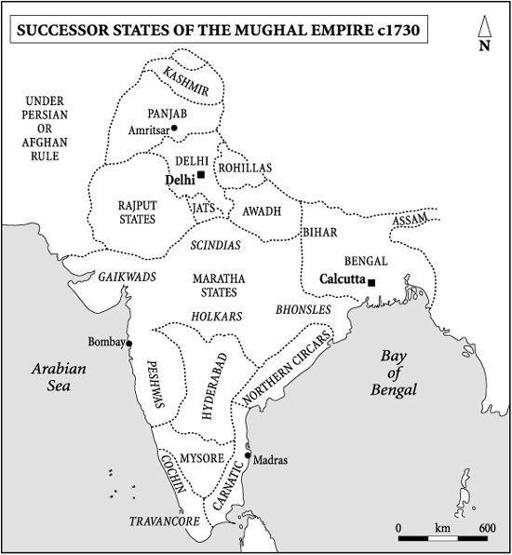

Later distributions and partitions aimed at the same kind of harmonised commonwealth. It was susceptible to direction but fell well short of an imperial formation. Individual leaders at the head of their own armies operated independently. Sometimes they clashed and sometimes they collaborated but more typically each operated within a separate sphere which was determined by previous operations and existing outposts or sanctioned by the award of particular revenues. Baji Rao’s exceptional talents ensured a degree of central control. But already the seventeenth-century Maratha ‘state’ had become the eighteenth-century Maratha ‘confederacy’.

As with the devolving provincial governments of the Mughal empire, sovereignty itself could be an elusive concept. Maratha demands continued to focus more on revenue than territory, and to reflect the awesome mobility of the Maratha horse. Thus Maratha rule bubbled up wherever the existing revenue system was vulnerable or wherever trade arteries converged. Sometimes it circumvented existing rulers or even accommodated them. Although incomprehensible to writers schooled on the definable certainties of the nation-state, Maratha dominion often rejoiced in the character of a parallel, or counter, administration.

The great confederate families who emerged during this period would become the princely Marathas of British times. All distinguished themselves militarily in the 1720s, although they were not necessarily

deshmukhs

with

ancestral lands in the Maratha homeland. Damaji Gaikwad for instance, the ancestor of the Gaikwads of Baroda, had served in Gujarat with a Maratha family that strongly opposed the peshwa and indeed fought against him in support of Nizam-ul-Mulk, the Mughal governor in the Deccan. Not till some years after the nizam’s defeat at Palkhed in 1728 did Damaji, by then supreme in Gujarat, declare his loyalty to the peshwa. On the other hand, Malhar Rao Holkar and Ranoji Scindia (Sindia, Shinde) rose entirely in the peshwa’s service, mostly in Malwa. Holkar performed with distinction at Palkhed and was rewarded with a large portion of Malwa including Indore, from where his descendants would rule as Maharajas of Indore. Scindia was awarded the ancient city of Ujjain although Gwalior, taken by his son Mahadji in 1766, would be the seat of future Scindia power and the most formidable Maratha maharaja-ship in northern India.

Likewise the Bhonsle supporters of Shahuji in his tussle with Tarabai were awarded revenue rights in Berar. These rights became the nucleus of Maratha power in eastern India whence raids were conducted deep into Orissa and Bengal. The Bhonsles adopted Nagpur as their capital, and it would be British annexation of this state of Nagpur, amongst others, which would contribute to the discontent which flared into the 1857 Uprising or ‘Indian Mutiny’. As for the sidelined Tarabai and her own Bhonsle protégés, they were eventually bought off with the offer of Kolhapur in southern Maharashtra. As a separate state under its own Maratha maharajas, Kolhapur would outlive both the Mughals and the peshwas and survive even the British, only to surrender its autonomy at Independence. Like all the other princely houses it was finally disestablished by Indira Gandhi in the 1970s.

Meanwhile the peshwas remained in Pune. Baji Rao, the second peshwa, had correctly surmised that with the power of the Mughals devolving to the empire’s provinces, the main challenge to Maratha expansion would come from regional regimes like those already emerging in Bengal and Awadh. Nizam-ul-Mulk, one of the most senior and able Mughal

amirs

, who had repeatedly rescued the imperial fortunes, reluctantly came to much the same conclusion. Instead of buttressing worthless emperors in Delhi, in 1723 he determined to carve out his own kingdom based on the Deccan province of which he was governor. Two formidable opponents, the Marathas, of course, and one Mubariz Khan, another Mughal functionary who had created a near-independent state based on Hyderabad, barred his way. In 1724 he defeated and killed Mubariz Khan but in 1728 and again in 1731 he was himself outmanoeuvred by the Marathas. Not surprisingly he eventually forsook his capital of Aurangabad and took his title, troops and aspirations east to Hyderabad. There he duly founded the strongest of all the newly devolved satellite states of the empire. It would also prove to be one of the most long-lived thanks to an eventual accommodation with the British.

FIRST THE

FARMAN

…

Farrukhsiyar, the protégé, scourge, and finally victim of the Saiyid brothers who in 1719 had rejected the agreement reached with Balaji Vishvanath, had in 1717 received another such request for imperial authorisation. It came

from the opposite quarter of his tottering empire, in fact from Calcutta, and after much prevarication he did in this instance give his consent. But the consequences proved no less fateful. On the strength of Farrukhsiyar’s imperial

farman

, ‘The Honourable Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies’ would line up with the Marathas and the nizam for a stake in the devolving might of the Great Mughals.

Ever since the days of Akbar the European trading companies had been petitioning the Mughal emperors for

farmans

, imperial directives. These would theoretically regularise their status, privileges and trading terms throughout the empire and would, as it were, trump the variety of vexatious exactions and demands imposed by local Mughal officials in the ports and provincial capitals. To an organisation like the English East India Company, whose very existence depended on a national monopoly of Eastern trade as solemnly conferred by charter from the English sovereign, the need for some such reciprocal authorisation guaranteeing favourable access to its most important trading partner was self-evident.