India: A History. Revised and Updated (76 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

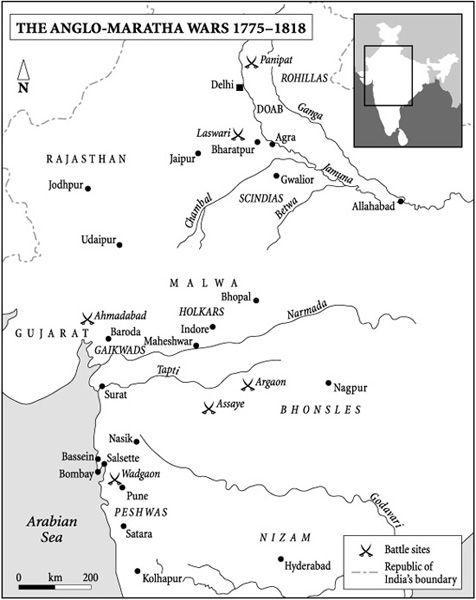

It was not quite the end of the Marathas. Richard Wellesley’s expensive campaigning had greatly embarrassed his masters in London. His gratuitous swipe at Holkar was the last straw. He was recalled from India in disgrace and his planned ‘settlement’ of central and western India never materialised. Nevertheless Delhi, Agra and the Ganga-Jamuna Doab were retained as a new salient of British territory in the north-west.

The new British frontier supposedly ran north along the Jamuna, although some chiefs from the slice of territory between the Jamuna and the Satlej (‘the Cis-Satlej states’) had also tendered their allegiance to General Lake. This brought the British into potential conflict with Ranjit Singh,

a young Sikh leader who had been prominent in repulsing Afghan attacks by Ahmed Shah Abdali’s successors and who, since occupying Lahore in 1799, had been pursuing a policy of conquest and alliance that mirrored that of the British. By 1805 he had secured the Sikh centre of Amritsar together with its potential for converting religious patronage into political authority. He had also impressed his personal authority on much of the Panjab, including some of those ‘Cis-Satlej chiefs’ as the British called them. But whilst Ranjit’s kingdom, like Tipu’s, would incorporate some European features and represent a serious challenge to the British, Ranjit himself was too much of a realist to invite the risks of war. By the Treaty of Amritsar in 1809 he backed down over the Cis-Satlej chiefs and thus the Satlej, rather than the Jamuna, became the Anglo–Sikh frontier. In return Ranjit secured British recognition of his independent authority as ‘Raja of Lahore’. Platitudes about friendship and non-interference would, for once, be respected and over the next thirty years the Raja of Lahore, comparatively free of British interference, would blossom into the Maharaja of the Panjab, creator of the most formidable non-colonial state in India.

Elsewhere the outcome of the Second Maratha War was less creditable. The British acquisition of the Ganga-Jamuna Doab was retained, mainly at the expense of Scindia whose ambitions were further constrained by a subsidiary alliance. But from central India and Rajasthan the British withdrew and disclaimed all authority, perhaps aghast at their own conquests and certainly alarmed by the high expenditure involved. The result was a predictable chaos. The Maratha leaders, impoverished, discredited and deeply resentful of the tightening British cordon, turned to indiscriminate plunder while many of their troops, despairing of payment, broke away to join bands of marauding adventurers, the so-called Pindaris. From Malwa, from the Bhonsles’ Berar, and from Rajasthan the chronic lawlessness spilled into the Deccan, Hyderabad, and the now-British Doab. Here was a clear case of British policy, or the lack of it, having created an anarchy which did indeed cry out for further intervention.

It came in 1817 in the form of an ambitious military sweep designed to wipe out these Pindari bands. The Maratha leaders were pressured into supporting this operation. But as they observed the political preparations for it, and noted the massive mobilisation, they became convinced that they were as much the target as the Pindaris. Suspicions deepened when the terms of a new British treaty recently forced upon the peshwa became known. Much harsher than that of Bassein, it included a clause by which the peshwa renounced any claim to supremacy over the other Maratha leaders. Although traduced in practice, the authority of the peshwa as a focus of loyalty was precious to all the Maratha leaders, and especially so to Peshwa Baji Rao II himself. Ostensibly assembling forces to co-operate in the action against the Pindaris, Baji Rao suddenly turned on the British contingent in Pune. The British Residency was razed and the British Resident – it was the future historian Mountstuart Elphinstone – barely escaped. Then the peshwa’s army marched against the British barracks nearby. It was repulsed and, when British reinforcements arrived, the peshwa fled. He remained at large until mid-1818, during which time his territories were systematically conquered.

A similar rising at Nagpur by the Bhonsle incumbent resulted in a similar conquest. In a now clichéd procedure, a minor was installed as maharaja of the much-reduced Nagpur state and was then shackled with all the paraphernalia of British clientage. For the peshwa, already lumbered with the status of a subsidiary British ally, there could be no such soft landing. His lands were annexed and, when eventually he was captured, he was deposed and banished into a long but comfortable retirement in the British Doab. The place chosen was near Kanpur (Cawnpore). There he died in 1851, and thence his adopted son, known as Nana Sahib, would be plucked from obscurity to raise again the flag of the peshwas during the great conflagration of 1857.

The Pindari War and this Third Maratha War ended the long defiance of the Marathas. In Maharashtra only the small states of Kolhapur and Satara, where ruled the tamed descendants of Shivaji himself, were left with any vestige of autonomy. To the rajputs of Rajasthan, as to the Maratha survivors in central India, the status of subordinate allies or ‘princely states’ was extended. ‘Except in Assam, Sind and the Panjab, British political supremacy was recognised throughout the whole subcontinent,’ writes Penderel Moon. ‘The Pax Britannica had begun.’

24

17

Pax Britannica

1820–1880

SIKH TRANSIT GLORIA

I

N MARKED CONTRAST

to, say, Napoleon’s adventure in Egypt, the British conquest of India was supposed to be self-financing. Although subject to increasing regulation and direction by the British government after 1776, the East India Company remained a business concern, run from stately offices in Leadenhall Street in the City of London, whose directors were primarily answerable to their stockholders. As with ships and cargoes, the recruitment and maintenance of troops had to be accounted for, and budgets had to be balanced. Before 1760 profits from trade had usually taken care of expenses. But as troop numbers and military overheads soared in the last decades of the eighteenth century, commercial receipts dwindled in significance. Now it was revenue in the form of indemnities, tribute and subventions from Indian states and of tax yields from directly administered territories which became the principal source of the Company’s income and so the mainstay of the

Pax Britannica

.

Conquests and annexations could be justified in terms of the additional revenue which they would in time undoubtedly yield; but they were expensive in themselves. The banquet of British victories was thus interspersed with periods of retrenchment during which the diners, pulling back from the table, savoured their latest acquisitions and insisted they would eat no more. Central to such digestive interludes was the assessment and forceful imposition in newly acquired territories of revised and usually harsher fiscal demands, or ‘revenue settlements’. The effect of these revenue settlements on India’s rural economy would prove significant. Here it may simply be noted that the order and stability which British rule undeniably brought did not come cheap. In the experience of most Indians

Pax Britannica

meant mainly ‘Tax Britannica’.

Nor, by any reasonable construction, could

Pax Britannica

be taken to mean actual peace, either in India or in the wider British empire. To maximise land revenue, frontiers had to be defended, marauding forest-and hill-peoples had to be excluded from taxable zones of settled cultivation, and these taxable zones had themselves to be extended into marginal areas of hill, forest and wetland. In that ‘the century beginning 1780 saw the beginnings of extensive deforestation in the subcontinent’,

1

the ‘Axe Britannica’ may bear as much responsibility as the ‘Tax Britannica’ for the desolated aspect of India’s post-colonial rural economy. Armed conflict with those outside this economy, whether along external political frontiers or internal ecological frontiers, was a concomitant of empire. By one reckoning there was not a single year between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War – the accepted duration of the

Pax Britannica –

when British-led forces were not engaged in hostilities somewhere in the world.

To this dismal record British India contributed substantially. Just before what the then governor-general was pleased to call ‘the pacification of 1818’ (that is the Pindari and Third Maratha Wars), British expeditions from India had invaded the East Indies (Indonesia) and Nepal. In the Indies a sharp little war (1811–12) involving twelve thousand Company troops relieved the Netherlands, then under Napoleonic control, of the island of Java and rewarded ‘the insolence’ of the island’s senior sultan with the desecration of his far-flung ‘Ayodhya’, otherwise Jogjakarta. Thomas Stamford Raffles, appointed lieutenant-governor of the island, reckoned Java ‘the Bengal of the East Indies’ and, greatly encouraged by the discovery of those inscriptions and monuments advertising the island’s ancient Indic associations, saw Java as the bridgehead for another British India. But it was not to be. Java was returned to the Dutch after Waterloo, and Raffles had to be content with a bridgehead on the south-east Asian mainland, namely Singapore.

The Gurkha War (1814–16) with Nepal went less smoothly but ultimately yielded some bracing Alpine territory in what are now Himachal Pradesh and Uttaranchal Pradesh. Unlike Java, these districts would be retained by the British; and although revenue yields would be disappointing, the amenity appeal of the outer Himalayas was quickly appreciated. Here in the 1820s and thirties were founded the choicest of hill-stations, including Naini Tal, Mussoorie, Dehra Dun and, above all, Simla, imminently to become what one of British India’s greatest military historians candidly calls ‘the cradle of more political insanity than any place within the limits of Hindustan’.

2

Continuing the catalogue of conflict, six years after the ‘pacification’

of 1818, the First Burmese War was declared against Burman incursions into Assam. By way of diversion an expedition was also sent to Rangoon. Assam itself was annexed in sections between 1826 and 1838, throughout which period troops were kept busy dealing with a succession of minor revolts in the Brahmaputra valley and a campaign in the Khasi hills. Meanwhile, in 1825–6, the Jat stronghold of Bharatpur, near Agra, had to be besieged for a second time, then stormed; in 1830–3 the hill peoples of Orissa were in constant revolt; and further military intervention was required in Mysore in 1830 to wrest the government from the perceived incompetence of its restored Wodeyar maharaja and in Coorg in 1834 to end by annexation the ambiguous status of this hilly enclave in the south-west corner of Karnataka. And all this, be it noted, during a twenty-year period of vigorous British retrenchment which is usually accounted one of peace and consolidation.

It would indeed seem so in retrospect. The campaigns of the 1830s were mere spats compared to the major wars of the 1840s, not to mention the near-meltdown of the 1850s. Of the wars in the 1840s all would be waged in the north-west of the subcontinent. With most of what today comprises the Republic of India already subject to direct or indirect British rule, it was now the turn of those lands which have since come to comprise Pakistan.

When Ranjit Singh, the Sikh Raja of Lahore, had been deprived of the ‘Cis-Satlej’ states after the Second Maratha War, British expansion for the first time crossed the watershed between the Ganga and the Indus to touch the present-day Indo–Pakistan frontier. That was in 1809, and it was not until a generation later that the banquet of conquest in the north-west was resumed. By then, the 1840s, Bengal had been dominated by the British for ninety years, Mysore for fifty. The Panjab, Sind, Kashmir and the Frontier can scarcely be called afterthoughts, since Wellesley had had his eye on the Panjab at the turn of the century. But their experience of colonial rule would be very much briefer and perhaps less traumatic. Spared the early years of British ‘rapacity’ as in Clive’s Bengal, spared the heady decades when the Company and its sepoy army competed with other Mughal successor states like the Marathas, and spared the deepening sense of military and religious betrayal which was about to flare into the conflagration of 1857, the peoples of the north-west would have a different perspective on British supremacy.

It was not more indulgent or collaborative, perhaps less so. But attitudes in the north-west were tempered by a historical experience in which alien conquest and migration had featured all too frequently. And amongst peoples, mostly Muslim, with a greater awareness of nineteenth-century European supremacy elsewhere in the Islamic world, these attitudes may have been more pragmatic. In the north-west, Sikhs as well as Muslims would find it easier to come to terms with colonial rule. By the mainly Hindu peoples of the rest of India they would even be thought to enjoy preferential treatment from the British. This, however, was not apparent in the 1840s. While substantial parts of what is now India had passed to the British by treaty and annexation, most of what is now Pakistan had to be physically conquered. The battles were more closely contested and the casualties proportionately heavier. This north-western addendum to British conquest would be both the most bloody and the most controversial.