India: A History. Revised and Updated (77 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

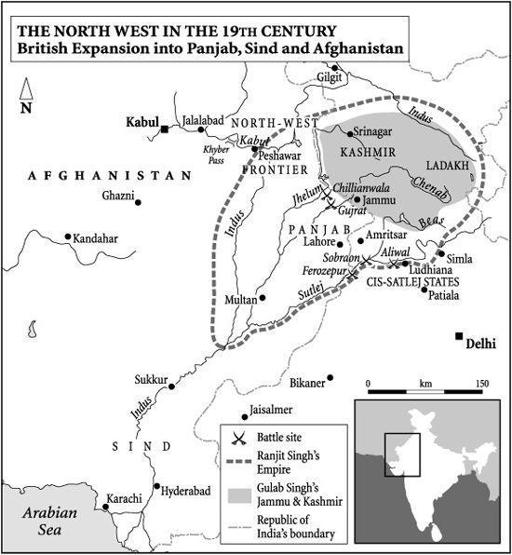

In a provocative mix of commercial ambition and strategic paranoia, the British government had in 1830 urged on Lord William Bentinck, the then governor-general, the desirability of opening the river Indus for steam navigation and of simultaneously assessing the danger to British India of Tsarist Russian expansion into central Asia. There followed various missions upriver and overland into the Panjab, Afghanistan and the great beyond of the central Asian Khanates. Copious reports were written, colourful narratives published, and new geographical ‘discoveries’ bagged. Cooler

heads insisted that the Indus, in so far as its erratic flow and shifting mudbanks allowed, was already ‘open’, that the idea of a Russian invasion of India was preposterous, and that such exploratory forays would only generate the hostility which they were supposed to pre-empt. But closer acquaintance with Afghan affairs obligingly fuelled the fantasies of alarmist bureaucrats and excited the ambitions of map-mad generals.

At the time Afghanistan’s existence as a viable and independent polity, rather than just a turbulent Indo–Persian frontier zone, lacked conviction. Kabul had indeed been a Mughal frontier province, but much of what subsequently became Afghanistan was usually under Uzbek and Persian rule. More recently Ahmad Shah Abdali’s fluctuating kingdom had relied heavily on its Indian conquests and anyway proved transitory; by 1814 his grandsons, one of them already blinded, had been ejected from Afghanistan. They repaired first to the Sikh kingdom of Lahore. There, from amongst the effects of Shah Shuja (the still-sighted grandson), Ranjit Singh extracted the Koh-i-Nur diamond as the price of his protection. Far from being a harbinger of misfortune, the gem was proving its worth as a life-saving talisman. In 1833 Ranjit Singh along with the British also assisted Shah Shuja in raising a force to reclaim his kingdom. It failed to do so and in the aftermath Dost Muhammad, the chief of a rival Pathan clan, established himself in Kabul.

Another British mission to Kabul in 1837 reported favourably of Dost Muhammad. British support of his claim to Peshawar, lately taken from Afghan rule by Ranjit Singh, was strongly urged; and in return Dost Muhammad was expected to prove a staunch ally against either Persian or Russian designs on India. To support this contention, the mission made much of the arrival in Kabul of a supposed Russian envoy who, if the British declined to take up Dost Muhammad’s case against Ranjit Singh, might himself do so on behalf of his Tsarist master.

This and other such reports were turned on their head by the ‘politically insane’ coterie of advisers who surrounded Lord Auckland, the most vacillating of governors-general, during his 1838 summer sojourn in Simla. The mere suggestion of Dost Muhammad receiving Russian encouragement now became proof of ‘his most unreasonable pretensions’, indeed of ‘schemes of aggrandisement and ambition injurious to the security and peace of the frontiers of India’. In great haste a tripartite alliance was arranged with Ranjit Singh and the exiled Shah Shuja. Dost Muhammad was to be ousted by force; Shah Shuja was to be installed in his place; the force itself was to be provided jointly by Ranjit Singh and Shah Shuja. But then, lest they prove half-hearted, a British expedition was organised to augment and, in

the event, dwarf the Sikh and Afghan contributions. This was ‘the Army of the Indus’, some twenty thousand strong with perhaps double that number of camp-followers, which in early 1839 marched circuitously across 1500 kilometres of patchy desert and instantly denuded cultivation to climb through the Bolan Pass into Afghanistan and thence, for the most part, never to return.

The First Afghan War is usually ranked as the worst disaster to overtake the British in the East prior to Japan’s World War II invasion of Malaya and capture of Singapore exactly a century later. In that in both campaigns most of the troops, and so most of the casualties, were Indian rather than British, this verdict conceals India’s human tragedy beneath a mound of imperial hubris. Even sepoys who were lucky enough to survive the rout in Kabul often found themselves outcastes when they returned to India. ‘This greatly mortified me,’ recalled Sita Ram, a captured brahman sepoy who escaped back to India and may be regarded as ‘a credible witness’.

3

In Afghanistan Sita Ram had been enslaved, some of his comrades had been forcibly converted to Islam, and all were deemed to have lost status by serving beyond the Indus, so contravening a high-caste taboo against travel outside India. The ostracism experienced by the survivors was so severe that ‘I almost wished I had remained in Cabool where at any rate I was not treated unkindly.’

4

This same prejudice against ‘overseas’ service had led to a small mutiny at the time of the Burmese war. But in Afghanistan troubled caste consciences went unsoothed by the balm of victory, and the later expense of caste reinstatement went unpaid by the spoils of conquest. Suddenly employment in the Company’s forces lost some of its popularity. Men thought less of unswerving loyalty to the Company and looked more closely at their terms of service.

Worse still, from the corpse-strewn gorges of the Kabul river, red-coated myths about the Company’s invincibility, its armies’ discipline and its officers’ courage emerged in tatters. A quick reinvasion and heavy reprisals would to some extent restore British pride; but, since the country was ultimately evacuated, questions arose about the political wisdom, indeed sanity, of the ‘tin gods’ who from Simla or Calcutta ordained these affairs.

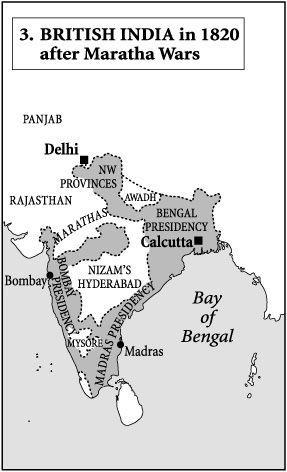

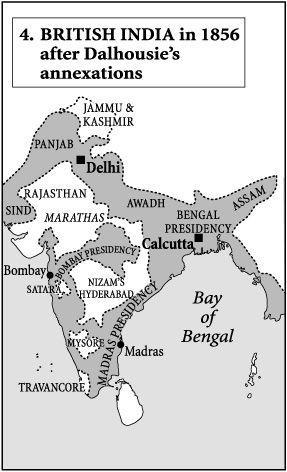

The conquest and annexation of Sind in 1843, a spin-off of the reinvasion of Afghanistan, did nothing to quell such doubts. Major-General Sir Charles Napier frankly admitted that ‘we have no right to seize Scinde’; yet he actively ‘bullied’ (his own word) the Sindis into hostilities and then conducted what he called this ‘very advantageous, useful, humane piece of rascality’ with maximum brutality. It contravened a sheaf of treaties, themselves signed under duress, which had previously been concluded with the various

rulers, or ‘amirs’, of Sind, and it incurred almost universal condemnation in Britain. The story that Napier, in one of the shortest telegraphs ever sent, announced his victory with a single Latin verb is apparently apocryphal. ‘

Peccavi

’ (meaning ‘I have sinned [i.e. Sind]’), was not unworthy of Napier’s wit, but it was in fact the caption given him by the magazine

Punch

; ‘and

Punch

represented him as confessing that he had sinned because the deposition of the Amirs and the seizure of their territories raised such a storm of criticism in England’.

5

Subsequently Sind, despite the development of Karachi as a major sea-port, failed to provide the revenue returns projected by Napier. Worse still, to the likes of sepoy Sita Ram it constituted another source of grievance in that, being for the most part beyond the pale of the Indus, garrison duty there carried the stigma of caste-loss without, since it was now British territory, the compensation of an ‘overseas’ allowance. Not unreasonably, Bengal troops posted to Sind were soon staging a succession of minor mutinies.

Mountstuart Elphinstone, who had led the first British diplomatic mission to Afghanistan in 1809, then been the last British Resident at the court of the peshwa in 1816 and later wrote that eminent history of India, likened Britain’s post-Afghanistan conduct in Sind to that of ‘a bully who had been kicked in the streets and went home to beat his wife’. But if the British were the bully, if Sind was the unfortunate wife and Afghanistan the lawless streets, it was Lahore which was the precinct boss. To avoid friction with Ranjit Singh, Dost Muhammad had been demonised; to avoid crossing his Sikh kingdom in the Panjab, the ‘Army of the Indus’ had marched to Afghanistan so circuitously; and to pre-empt a Sind–Sikh alliance, the amirs had been deposed. Novel though it was, the British were tiptoeing round the sensibilities of an Indian ruler. In Ranjit Singh it seemed as though the tide of British conquest had rolled up against a cliff of Panjabi granite.

Following his non-aggression Treaty of Amritsar with the British in 1809, Ranjit had by 1830 created a kingdom, nay an ‘empire’, rated by one visitor ‘the most wonderful object in the whole world’.

6

In addition to uniting the Panjab, a phenomenal achievement in itself given the rivalries of its Muslim, Hindu and Sikh factions, and then reclaiming Multan and Peshawar, the ‘Raja of Lahore’ had also conquered most of the Panjab hill states and occupied Kashmir. In 1836 one of his Dogra vassals then overran neighbouring Ladakh at the western extremity of the Tibetan plateau; and from there in 1840, in one of those rare examples of Indian military aggression beyond its natural frontiers, Zorawar Singh, a Dogra general, actually invaded Tibet itself. Like the ‘Army of the Indus’ – and at almost exactly the same time (1840–1) – this expedition enjoyed initial success and then sensational disaster. In mid-winter at five thousand metres above sea-level Zorawar’s six thousand frostbitten Dogras were confronted by a Chinese host twice as numerous and infinitely better clad. ‘On the last fatal day not half of his men could handle their arms.’ Those who could, fled; the Chinese scarcely bothered to follow, ‘knowing full well that the unrelenting frost would spare no one’.

7

This, however, was a minor reverse and, bar the temperatures, not otherwise comparable to Napoleon’s débâcle in Russia thirty years earlier. Defeat in central Tibet barely registered on the morale of the Lahore army; and like the long-forgotten empire of Kanishka, the Sikh realm still straddled the Himalayas. As contemporaries and, to the British, formidable opponents, Ranjit and Bonaparte invited more obvious comparisons. A

French traveller declared the misshapen Sikh ‘a miniature Napoleon’; and the British agreed that both were ‘men of military genius’. Moreover ‘the Sikh monarchy was Napoleonic in the suddenness of its rise, the brilliancy of its success, and the completeness of its overthrow.’

8

The comparisons were particularly apposite because of Ranjit’s enthusiasm for employing distinguished ex-Napoleonic officers. Under his direction Generals Avitabile and Ventura, Colonels Court and Allard and a host of others converted his infantry and artillery into a sepoy army as effective as that of the Company. ‘In training, weapons, organisation, tactics, clothing, system of pay, layout of camps, order of march, regular units of the Sikh army resembled their [British] opponents as closely as they could; indeed in battle it was possible to tell the scarlet-coated sepoy of the Bengal army from the scarlet-coated Sikh only by the colour of his belt.’

9

Including Muslims and Hindus of Dogra, Jat and rajput origin, the ‘Sikh army’ was a pan-Panjabi army, but with a Sikh core. ‘It may be safe to suggest that more than half of the men … were Sikh, which would mean about fifty thousand.’

10

In the councils of state and the rewards of office Sikhs similarly predominated. To Ranjit’s rule, and especially to his army, Sikhism lent something of that distinctive identity and unity of purpose which characterised the command structure of the Company and made the British so formidable.