India: A History. Revised and Updated (37 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

More immediately the siege engines came into their own. The land forces had effected a rendezvous with the seaborne reinforcements outside Debal, but they were unable to force entry to the city. Even the

manjanik

, a gigantic martinet, or calibrated catapult, which required five hundred men to operate it, was ineffective against Debal’s stout walls. But by shortening its chassis so that it aimed high, the

manjanik

was trained on a flagstaff whose bright red flag fluttered defiantly from the top of Debal’s temple tower. After no doubt several misses, the

manjanik

-master struck lucky and the flagstaff was shattered, ‘at which the idolaters were sore afflicted’. In fact, they threw caution to the wind and, issuing forth to avenge this sacrilege, were easily routed. ‘The town was thus taken by assault and the carnage endured for three days,’ says al-Biladuri. The temple was partly demolished, its ‘priests’ (who may have been Buddhists or brahmans) were massacred, and a mosque was laid out for the four-thousand-man garrison which was to remain in Debal.

Meanwhile ibn Qasim moved inland, then up the west bank of the Indus. Some ‘Samanis’ (presumably

sramanas

, or Buddhist monks) of ‘Nerun’ (perhaps the Pakistani Hyderabad) were reminded of their vows of non-violence and came to terms with the invader. Thanks to these

‘Buddhist fifth-columnists’,

4

as an eminent Indian historian mischievously calls them, Nerun capitulated. On the opposite bank of the river, a despondent Dahar was apparently safe since ibn Qasim seemed unable or unwilling to cross the flood. Eventually orders came from Governor al-Hajjaj in Baghdad to do just that. A bridge of roped boats was assembled on the west bank. With one end released into the current, it swung into place and the Arabs began crossing immediately.

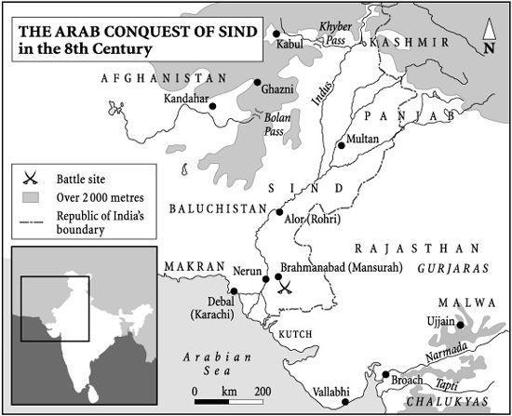

‘The dreadful conflict which followed was such as had never been heard of,’ reports al-Biladuri. It does, though, bring to mind Alexander’s titanic struggle with Poros; for again the Indian forces displayed exceptional bravery and again the outcome hung in the balance until decided by the ungovernable behaviour of panic-stricken elephants. The beast ridden by Dahar himself, a rather conspicuous albino, was hit by a fire-arrow and plunged into the river. There Dahar made an easy target. He fought on with an arrow in his chest but, dismounting, was eventually struck by a skull-splitting sword blow. It was towards evening, according to al-Biladuri, and when Dahar ‘died and went to hell’, ‘the idolaters fled and the Mussulmans glutted themselves with massacre’.

Muhammad ibn Qasim then resumed his march upriver. Brahmanabad (the later Mansurah), then Alor (Rohri) and finally Multan, the three principal cities of Sind, were either captured or surrendered, probably during the years 710–13. Astronomical casualty figures are given, yet both al-Biladuri and the

Chach-nama

agree that ibn Qasim was a man of his word. When he offered, in return for a peaceful surrender, to spare lives and guarantee the safety of temples he was as good as his promise. Hindu and Buddhist establishments were respected ‘as if they were the churches of the Christians, the synagogues of the Jews or the fire temples of the Magians [Zoroastrians]’. The

jizya

, the standard poll-tax on all infidels, was imposed; yet brahmans and Buddhist monks were allowed to collect alms, and temples to receive donations. Ibn Qasim was no mindless butcher. When he was disgraced and removed following the death of his patron al-Hajjaj, it may well be that ‘the people of Hind wept’.

Al-Biladuri merely explains that Muhammad ibn Qasim was sent back to Iraq as a prisoner and there tortured to death because of a family feud with the new governor. The

Chach-nama

gives a different story and much more detail. Apparently ibn Qasim had previously captured two of Dahar’s virgin daughters and sent them to Baghdad as an adornment to Caliph Walid’s seraglio. There one of the young princesses, Suryadevi, caught the caliph’s eye; but when he deigned to draw her near, ‘she abruptly stood up’. As she very respectfully explained, she felt unworthy of the royal couch

since both she and her sister had been similarly favoured in Sind during their detention by Muhammad ibn Qasim. The caliph was not pleased. ‘Overwhelmed with love and letting slip the reins of patience’, he immediately dictated a missive ordering the perpetrator to ‘suffer himself to be sewed up in a hide and sent to the capital’.

The order was obeyed to the letter; the needles and the thread were at last put to good use and ibn Qasim, trussed and labelled, was despatched to Baghdad. Two days into this long and excruciating journey ‘he delivered his soul to God and went to the eternal world’. When finally the unsavoury package was delivered to Walid, the princesses were invited to bear witness to the caliph’s awesomely impartial justice. Not without glee they surveyed the grisly cadaver and then bravely, if unwisely, revealed that Muhammad ibn Qasim had in fact behaved with perfect propriety.

But he had killed the king of Hind and Sind, destroyed the dominion of our forefathers, and degraded us from the dignity of royalty to a state of slavery. Therefore, to retaliate and revenge these injuries, we uttered a falsehood and our object has been fulfilled.

So Muhammad ibn Qasim had been stitched up in more ways than one. Again the Caliph was mightily displeased, ‘and from excess of regret he bit the back of his hand’. Then he consigned the princesses to lifelong incarceration.

5

Like most good stories, this one has not always been endorsed by professional historians, although why a Muslim should have fabricated a tale so creditable to the infidel is not explained. It does, moreover, offer a plausible reason for the downfall of Sind’s respected and highly successful conqueror. His like would be hard to find. The next Arab governor of the province died on arrival, and his successor seems to have made little impact on a situation which had already declined, with Brahmanabad back under the control of Dahar’s son. The latter, in c720, accepted Baghdad’s offer of an amnesty whereby in return for adopting Islam he was granted immunity and the chance to participate in government. But this looks to have been a tactical move for, as a succession crisis engulfed the Umayyad caliphate, the Sindis happily discarded both their allegiance and their new faith.

Dahar’s son was eventually captured and killed by Junaid ibn Abdur Rahman al-Marri, who in the mid-720s seems to have recovered much of the province – and more besides. His successors fared less well, and there is evidence of the caliph’s governors being penned within fortified enclaves before again ‘seizing whatever came into their hands and subduing the neighbourhood whose inhabitants had rebelled’.

6

This pattern continued

to repeat itself during the early years of the Abbasid caliphate. Baghdad’s control of the entire province remained a rare phenomenon until, c870, the local governors, or amirs, gradually threw off their allegiance to the caliph and managed matters for themselves.

By the tenth century the province was divided between two Arab families, one ruling from Mansurah in the south and the other from Multan in the north. In Multan the resentment of the still largely non-Muslim population was curbed only by their Muslim masters threatening to vandalise the city’s most revered temple whenever trouble stirred or invasion threatened. If conquest had been difficult, conversion was proving even more so. Yet the obstinacy of the idolaters, if indulged, could be put to some advantage, and if condemned, always afforded an excellent justification for pillage and plunder. So it was in Sind and so it would be in Hind (i.e. India). In fact Sind’s governors had already had a foretaste of what lay ahead. Muhammad ibn Qasim may have pushed east towards Kanauj, Junaid certainly tried his luck in western India, and later governors may have followed suit.

Their experiences, in so far as they can be inferred from the scanty evidence, would not be encouraging. Al-Biladuri claims conquests for Junaid which extended to Broach in Gujarat and to Ujjain in Malwa. From a copper plate found at Nausari, south of Broach, it would appear that the Arabs had crossed Saurashtra and so must have squeezed through, or round, the Rann of Kutch. This was the incursion which put paid to the Maitrakas of Vallabhi, they of the dazzling toenails whose enemies’ rutting elephants had had their temples cleft. It was also the incursion which was finally halted by, amongst others, a vassal branch of the Chalukya dynasty. The date is thought to have been c736.

Ujjain and Malwa look to have been the target of a separate and probably subsequent offensive by way of Rajasthan.

7

It too was defeated, in this instance by a rising clan of considerable later importance known as the Gurjaras. Clearly, when the subcontinent first faced the challenge of Islam, it was neither so irredeemably supine nor so hopelessly divided as British historians in the nineteenth century would suppose.

THE RISE OF THE RASHTRAKUTAS

In contemporary Indian sources these first marauding disciples of Islam are occasionally identified as

Yavanas

(Greeks),

Turuskas

(Turks) or

Tajikas

(Tajiks or Persians), but more usually as

mlecchas.

The latter term meant

what it always had: foreigners who could not talk properly, outcastes with no place in Indian society and, above all, inferiors with no respect for

dharma.

Like all

mlecchas

the Muslims were seen as essentially marginal, negative and destructive, just like the Huns. There is no evidence of an Indian appreciation of the global threat which they represented; and the peculiar nature of their mission – to impose a new monotheist orthodoxy by military conquest and political dominion – was so alien to Indian tradition that it went uncomprehended.

No doubt a certain complacency contributed to this indifference. As al-Biruni (Alberuni), the great Islamic scholar of the eleventh century, would put it, ‘the Hindus believe that there is no country but theirs, no nation like theirs, no king like theirs, no religion like theirs, no science like theirs.’ He thought they should travel more and mix with other nations; ‘their antecedents were not as narrow-minded as the present generation,’ he added.

8

While clearly disparaging eleventh-century attitudes, al-Biruni thus appears to confirm the impression given by earlier Muslim writers that in the eighth and ninth centuries India was considered anything but backward. Its scientific and mathematical discoveries, though buried amidst semantic dross and seldom released for practical application, were readily appreciated by Muslim scientists and then rapidly appropriated by them. Al-Biruni was a case in point: his scientific celebrity in the Arab world would owe much to his mastery of Sanskrit and access to Indian scholarship.

Aspects of eleventh-century India which al-Biruni omitted from his catalogue of criticism were its size and its wealth. Unlike Alexander’s Greeks, Muslim invaders were well aware of India’s immensity, and mightily excited by its resources. As well as exotic produce like spices, peacocks, pearls, diamonds, ivory and ebony, the ‘Hindu country’ was renowned for its skilled manufactures and its bustling commerce. India’s economy was probably one of the most sophisticated in the world. Guilds regulated production and provided credit; the roads were safe, ports and markets carefully supervised, and tariffs low. Moreover capital was both plentiful and conspicuous. Since at least Roman times the subcontinent seems to have enjoyed a favourable balance of payments. Gold and silver had been accumulating long before the ‘golden Guptas’, and they continued to do so. Figures in the Mamallapuram sculptures and the Ajanta frescoes are as strung about with jewellery as those in the Sanchi and Amaravati reliefs. Divine images of solid gold are well attested and royal temples were rapidly becoming royal treasuries as successful dynasts endowed them with the fruits of their conquests. The devout Muslim, although ostensibly bent on converting the infidel, would find his zeal handsomely rewarded.

Thanks to the peculiarities of the caste system, Indian society also seemed admirably stable, if excessively stratified. But although in theory the ritual-and-pollution-based

varna

, and in practice the professionbased

jati

, precluded social mobility, Muslim writers seldom correctly identified the four

varnas

or divined the variety of the innumerable

jatis.

It would seem, then, that the ‘system’ was not obviously systematic. Kings of

sudra

or brahman origin, like those of Sind, were as common as those whose forebears were, or pretended to be, of the supposedly royal and martial

ksatriya varna.

Nor was caste wholly prohibitive and repressive. Indeed it has been argued that caste membership conferred important rights of participation in the economic and political processes as well as obligations of social conformity. In other words, it was as much about being a citizen as being a subject. Through various rural and, more obviously, urban assemblies like caste and guild councils, endorsement of a particular leadership was demonstrated by attendance in the myriad rituals of state. ‘Rather than being excluded from the life of Indian polities, [castes] actively participated in it. Indeed, by doing so, they partly constituted it.’

9

Such participation in, for instance, the elaborate ceremonies involved in installing a new king or launching a

digvijaya

signified assent to the traditional fiscal and military expedients available to such a leader. But by caste councils, as by reluctant feudatories and vassals, such connivance in the political order might always be subtly withheld or transferred.