India: A History. Revised and Updated (33 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

This ‘feudalism from below’ is sometimes contrasted with that ‘from above’, the latter being epitomised in the royal hierarchy of a

maharajadhiraja

surrounded by his proliferating feudatories or

maha-samantas

(literally ‘great neighbours’ but now signifying dependent dynasties and vassals). Both contributed to the process of fragmentation, ‘feudalism from above’ by regionalising authority even as the kings who exercised it shrilly proclaimed their universal sovereignty, and ‘feudalism from below’ by a more insidious erosion of the loyalties and resources on which all authority depended.

HARSHA-VARDHANA

As if to contradict such theorising, a new ‘king-of-kings’ was nevertheless about to shine forth in fleeting brilliance. A new chronological era, always a significant pointer, would be inaugurated; and another ‘victorious circuit of the four quarters of the earth’ (

digvijaya

) would be celebrated. In the early seventh century the rival dynasties, which like close-packed clouds had clustered over

arya-varta

ever since the great Guptas, began to thin. The monsoon, it seemed, had been delayed; northern India was about to experience a last searing glimpse of pre-Islamic empire.

Of the no doubt many

sasana

issued by Harsha-Vardhana of Thanesar (and later Kanauj) few survive. A single seal, once presumably attached to a copper plate, does however list Harsha’s immediate antecedents. Apparently he belonged to the fourth Vardhana generation; his father had been the first to assume the title

maharajadhiraja

and his brother the first to

call himself a follower of the Buddha. Harsha seems to have adopted both styles, although his Buddhist sympathies would preclude neither aggressive designs nor the worship of orthodox deities. Sadly the seal in question has no room for further information, and were it, and his coins, the only evidence of Harsha, he would be but another shadowy dynast.

Mercifully, though, the somewhat sterile evidence provided by

sasana

is supplemented by two much more informative witnesses. One was Hsuan Tsang (Hiuen Tsiang, Hsuien-tsang, Yuan Chwang, Xuan Zang,

etc.

etc.), a Chinese monk and scholar who, inspired by Fa Hian’s pilgrimage to the Buddhist Holy Land two hundred years earlier, himself spent the years 630–44 visiting India. He returned to China with enough Buddhist relics, statuary and texts to load twenty horses, and subsequently wrote a long account of India which, except in the case of the extreme south, seems to have been based on personal observation.

The other and the more endearing witness was Bana, an outstanding writer and also, incidentally, a rakish brahman whose ill-spent youth and varied circle of friends ‘shows how lightly the rules of caste weighed on the educated man’.

6

Of Bana’s two surviving works the most important is the

Harsa-carita

, a prose account of Harsha’s rise to power. Though more descriptive than explanatory, and though loaded with linguistic fancies and adjectival compounds of inordinate length, it rates as Sanskrit’s first historical biography as well as a masterpiece of literature. In it the hectic excitement of camp and court is conveyed with all the vivid incident of a crowded Mughal miniature. Forest and roadside teem with life as Bana minutely observes every detail of rural industry and identifies every species in the natural environment. No Kipling, no Rushdie better evokes India’s heaving vitality or the lifelong industry of its people.

Inevitably both Hsuan Tsang and Bana were interested parties. The former depended on Harsha’s protection and the latter on his patronage. In no sense is either of their works a critical appraisal. Hsuan Tsang was blinded by a Buddhist bigotry which he would fain hoist on Harsha, while Bana saw Harsha and history as combining to provide the material for a historical romance. Yet in a way each author complements the other, the Chinese monk providing the outline and the Indian author the detail, the Buddhist the libretto and the brahman the music.

They also complement one another chronologically. Hsuan Tsang would coincide with the climax of Harsha’s career while Bana records only his early years, from his birth in c590 to his accession in c606 and his first campaign soon after. This period is of particular interest since Harsha, as a second son, was not the obvious successor. His father,

Maharajadhiraja

Prabhakara-Vardhana, died when Harsha and his elder brother were away, the latter fighting the Huns while the teenage Harsha enjoyed a spot of hunting. Harsha got home first and alone saw the dying king, at which meeting, according to Bana, he named him as his heir. The brother then returned victorious from the battlefield with his troops. Harsha said nothing of their father’s last wish and the brother therefore remained heir presumptive.

At this point Bana introduces yet another reason for Harsha’s succession. Apparently Rajya-Vardhana, the brother, was so overcome with grief over their father’s death that he declined the throne and opted to retire to a hermitage. Improbably he too, therefore, insisted that Harsha succeed their father. Yet from other sources, including Hsuan Tsang, it is known that in fact it was Rajya-Vardhana who succeeded. Bana, in short, protests too much. Perhaps he simply wanted to bolster Harsha’s legitimacy by suggesting that he was the direct heir. Or perhaps he had a less creditable motive. As a recent biographer delicately puts it, ‘it is hard to escape the conclusion that the unusual twists in the story … were rendered inevitable because of some episode uncomplimentary to the author’s hero.’

7

More specifically it may be that Bana was trying to lull suspicions, still current at the time he was writing, that Harsha had had a motive, if not a hand, in Rajya-Vardhana’s imminent removal.

This came about as a result of more ‘unusual twists’. Rajya-Sri, the princes’ sister, had been married to their neighbour and ally, the Maukhari king of Kanauj. In the midst of the succession crisis in Thanesar, this Maukhari king was suddenly attacked by the king of ‘Malava’ (presumably Malwa). The Maukhari king died in battle; Rajya-Sri was taken hostage; and the victorious ‘Malava’ now moved to attack Thanesar. In this desperate situation it was not Harsha but again his brother who took the initiative. Suddenly abandoning his idea of a quiet life of grief, he now insisted on his right to revenge. Harsha’s wish to accompany him was swept aside and, taking ten thousand cavalry, the righteous Rajya-Vardhana raced off to give battle.

Clearly an awesome campaigner, Rajya-Vardhana duly routed the men from Malwa. But then the real villain of the piece emerged. Sasanka, king of Gauda in Bengal, had been assisting the Malwa forces. The victorious Rajya-Vardhana met Sasanka under a safe-conduct, presumably to arrange a truce, and was treacherously murdered. At last the stage was clear for the young and hitherto somewhat subdued Harsha to explode upon it.

Instantly on hearing this [the news of his brother’s murder] his fiery spirit blazed forth in a storm of sorrow augmented by flaming flashes of furious wrath. His aspect became terrible in the extreme. As he fiercely shook his head, the loosened jewels from his crest looked like live coals of the angry fire which he vomited forth. Quivering without cessation, his wrathful curling lip seemed to drink the lives of all kings. His reddening eyes with their rolling gleam put forth, at it were, conflagrations in the heavenly spaces. Even the fire of anger, as though itself burned by the scorching power of his inborn valour’s unbearable heat, spread over him a rainy shower of sweat. His very limbs trembled as if in fright at such unexampled fury…

He represented the first revelation of valour, the frenzy of insolence, the delirium of pride, the youthful avatar of fury, the supreme effort of hauteur, the new age of manhood’s fire, the regal consecration of warlike passion, the camp-lustration day of reckoning.

8

Understandably his supporters were impressed. Ably, and of course volubly, encouraged by his commander-in-chief and then by the commandant of his elephant corps, Harsha mobilised ‘for a world-wide conquest’. Meanwhile his enemies were beset by all manner of ill omens: jackals, swarming bees and swooping vultures terrorised their cities; their soldiers fell out with their mistresses while some, looking in the mirror, saw themselves headless; a naked woman wandered through the parks ‘shaking her forefinger as if to count the dead’.

Sasanka, ‘vilest of Gaudas’, would be Harsha’s main objective but, Gauda being thousands of kilometres to the east of Thanesar, many other kings would have to submit first. One, evidently a hereditary rival of the Gauda kings, quickly entered into a treaty of friendship and subordinate alliance with Harsha. This was Bhaskara-varman, king of Kumara-rupa (Assam) on Gauda’s northern border. Sasanka would therefore have to fight on two fronts. Additionally Harsha could count on the forces of the Maukharis and on the defeated Malwa army which was now put at his disposal by his late brother’s commander.

The latter also brought news of the escape from her confinement in Kanauj of Rajya-Sri (Harsha’s sister and the queen of the Maukharis). Unfortunately she had fled into hiding in the Vindhya hills where, as a widow, she was thought to be about to commit

sati

. Harsha had other plans. He saw both merit and, though unmentioned by Bana, advantage

in rescuing her. Dousing his rage, therefore, he led a search party into the wild tracts of central India. A community of pioneers who were busily engaged in harvesting forest produce and clearing trees knew nothing of her whereabouts. But at another settlement, this time of assorted Buddhists, brahmans and other renunciates who were pooling their insights in an admirable spirit of ecumenism, he heard tell of a party of grief-stricken ladies hiding nearby. Rajya-Sri, horribly scratched and reduced to rags by her forest odyssey, was amongst them. In the nick of time she was duly plucked from her funeral pyre and reunited with her brother.

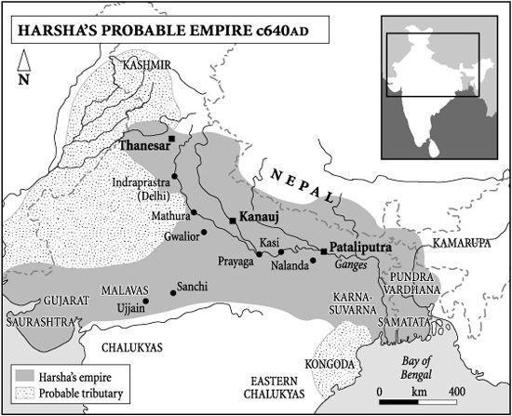

Rajya-Sri’s only wish now was to become a Buddhist nun. Harsha would not hear of it. He needed her active support and insisted on her accompanying him. As the Maukhari queen, she was vital to his plans since, through her, he in effect controlled the Maukhari kingdom. As a result of this identity of interest he would subsequently move his capital from Thanesar to the more central and significant city of Kanauj. Kanauj now became the rival of Pataliputra as the imperial capital of northern India and, through many vicissitudes and changes of ownership, would remain so until the twelfth century.

Meanwhile the campaign could be renewed. Accompanied by Rajya-Sri and a Buddhist sage who was to act as her confessor, Harsha hastened back to rejoin his army encamped by the Ganga. There, as he related the story of his successful rescue mission, the shadows lengthened and the sun went down in a blaze of gory omens, each of which presaged an imminent victory. The evening, says Bana, advanced as if ‘leaning on the clouds’ which were flecked and bright with the setting sun, like an ocean sunset. Then, with darkness closing in, the Spirit of Night respectfully presented Harsha with the moon; it was ‘as if the moon were a cup to slake his boundless thirst for fame’, says Bana, or even ‘a

sasana

of silver issued by king Manu himself entitling Harsha to conquer the seven heavens and restore the golden age’. And so, somewhat unexpectedly, amidst a welter of page-long adjectival compounds and with a well-flagged trail of conquest stretching into the distant future, Bana’s tale abruptly ends.

If there was more, it has not survived. Instead there is only the odd inscription plus the testimony of Hsuan Tsang, by the time of whose visit Harsha the teenage Galahad had become Harsha the middle-aged Arthur and his little kingdom on the Jamuna a universal dominion over the ‘Five Indies’. What this term actually comprehended is not clear. ‘He went from east to west,’ says Hsuan Tsang, ‘subduing all who were not obedient; the elephants were not unharnessed, nor the soldiers unbelted. After six years he had subdued the Five Indies.’

9

The division of India into five parts – north (

uttarapatha

), south (

daksinapatha

), east, west and centre (

madhyadesa

or

arya-varta

) – was fairly standard; but if this was what Hsuan Tsang meant by the ‘Five Indies’, he was grossly exaggerating. Harsha had indeed triumphed throughout much of north India, but his conquests were often tenuous and short-lived; they would take much longer than six years; and they certainly never included the Deccan or the south.

From his camp beside the Ganga, where Bana had left him basking in the prospect of bloody victories to come, Harsha seems to have continued east. Prayaga (Allahabad), Ayodhya, Sravasti, Magadha and a host of minor kingdoms in UP and Bihar, many of them previously under Sasanka’s sway, must have submitted before he sighted his quarry. According to a much later source, the great encounter with Sasanka of Gauda took place at Pundra in northern Bengal. Sasanka was apparently defeated, but not so decisively as to forfeit his kingdom, for he continued to rule Gauda itself and seems even to have reclaimed parts of Orissa and Magadha. Only after Sasanka’s death in c620–30 did Harsha successfully claim these kingdoms and apparently share them with his Assamese ally.