India: A History. Revised and Updated (35 page)

Read India: A History. Revised and Updated Online

Authors: John Keay

Tags: #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #India, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #History

A no less exasperated attitude is detectable in many nineteenth-century attempts to reconstruct India’s history. From inscriptions and

sasana

the flowery epithets about lotus-footed ancestors and star-bright toenails were ruthlessly discarded in an effort to extract some credible nugget of political or genealogical import. The

raja-mandala

as a useful symbol of political relations suffered the same fate. Crudely, it represented the idea that just as cosmic harmony depended on the hierarchy of gods and men actively participating in the triumph of

dharma

, so political harmony depended on the triumph of

dharma

through an ordered hierarchy of kings. But because this earthly hierarchy was constantly under threat from the

matsya-nyaya

(the ‘big fish eats little fish’ syndrome), it required frequent adjustments.

The

raja-mandala

, in which the

maharajadhiraja

took the place of Mount Meru at the centre or axis, demonstrated the basic principle of these adjustments. Thus the immediate neighbours of the axial ‘king of kings’, those therefore within the first circle, are to be regarded as his natural enemies; those beyond them in the next circle are his potential allies; those in the third circle are his enemies’ potential allies, those in the fourth his allies’ natural allies, and so on. According to Kautilya, this was the basis of all external relations and of any world order.

Additionally the

raja-mandala

, when represented as a diagram, was divided by vertical and horizontal radials into four quadrants or quarters. These were seen to correspond to the four

dwipa

, or lands, of a

mandala

map. Harsha’s

digvijaya

, or ‘conquest of the four quarters’, was therefore a bid for universal dominion. In the same way the

maharajadhiraja

who would be a

cakravartin

, a ‘wheel-turning’ world-ruler, must as it were weld the rims to the hub by spokes of conquest and alliance and so oblige the kings within each circle of the

mandala-raja

to acquiesce in and harmonise with his new and, of course, self-centring world order.

This geography, indeed geometry, of empire was crucial. It presupposed that ‘society of kings’ already mentioned and it necessitated frequent or,

in the case of Harsha and Pulakesin, almost continual perambulation of one’s domains. But it also made conflict a largely dynastic affair which, though of great frequency, may have been of low intensity. The troops involved seem to have been professional warriors who, while dependent on local supplies and transport, otherwise left the agricultural classes alone, as in Megasthenes’ day. Acts symbolic of submission were highly prized; so was the acquisition of accumulated wealth, war elephants, musical instruments, jewels and other symbols of sovereignty. On the other hand the heavy casualties and widespread devastation implied by boasts of ‘annihilation’ cannot be substantiated, nor is there evidence of any consequent economic collapse. On the contrary, the ease with which ‘uprooted’ kings again took root suggests an almost ritualised form of warfare not unlike that which survived, even into the twentieth century, amongst another society of Hindu kings – namely that on the Indonesian island of Bali.

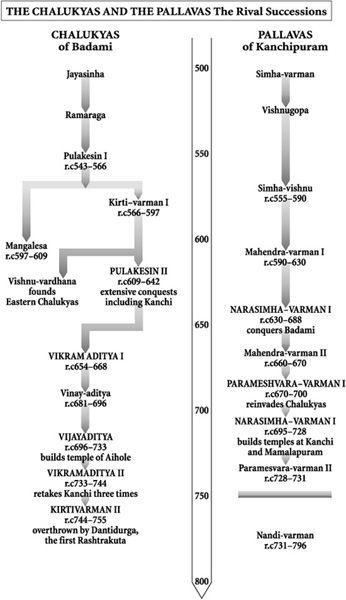

Back in the south India of the seventh century, while Pulakesin II was still celebrating his success in overrunning the rich Pallava country in Tamil Nadu, the Pallava king was ready to take the field again. At Polilur, a place near Kanchipuram where the British would suffer one of their worst defeats in India, the Pallava king claims to have ‘annihilated his enemies’, presumably the Chalukyas, and by 642 he was marching on their capital at Badami. Pallava records claim that Badami was then destroyed and that the Pallava king, Narasimha-varman I, made such a habit of defeating the great Pulakesin II that he fancied he could read the word ‘victory’ engraved on his adversary’s backside as he again took to flight. More certainly Narasimha-varman engraved a record of his success on a rock at Badami and thereafter assumed the title of

Vatapi-konda

, ‘conqueror of Vatapi [i.e. Badami]’.

The Chalukyas would return the compliment. Pulakesin seems to have died in the midst of these reverses and the Chalukyan kingdom to have remained in relapse during a succession crisis. But in 655 one of Pulakesin’s sons, Vikramaditya I, claimed the throne, quickly reasserted Chalukyan sovereignty, and was soon hammering again at the Pallavas. This time Kanchi was surrendered. Then once again the Pallavas struck back. With intermissions while the Pallavas dealt with the Pandyas of Madurai to the south or went to the aid of their allies in Sri Lanka, and while the Chalukyas saw off their own rivals, including the first Arab incursion into Gujarat, the ding-dong struggle between the paramount powers of the arid Deccan and lush Tamil coast continued for over a century. Not infrequently it well demonstrated the Kautilyan

raja-mandala.

The Pandyas, the southern neighbours and so natural enemies of the Pallavas, assisted the Chalukyas, while the Pandyas’ neighbours and natural enemies, the Cheras of Kerala and the kings of Sri Lanka, rendered support to the Pallavas.

In c740 Vikramaditya II, a Chalukya, again captured Kanchi and this time took the opportunity to leave a record of his success. His inscription in the soft sandstone of one of the pillars of the Pallavas’ just-built Kailasanatha temple is still legible and boasts not only of his conquest but also of his generosity to the city, which he spared, and to the temple, to which he

returned the gold that belonged to it. Significantly, as with the Pallava inscription at Badami, no attempt seems to have been made to erase this patronising record when the Pallavas duly recovered their capital.

Nor does this almost constant warfare with its frequent ‘annihilations’ seem to have inhibited either dynasty in the practice of kingship. The

sasanas

, from which our knowledge of their struggles is largely derived, continued to be issued; and the great temples, for which both dynasties are now best remembered, continued to be built. Narasimha-varman I, Pulakesin II’s eventual conqueror, was also known as Mahamalla or Mamalla (‘great wrestler’), and after him the Pallavas’ main port at Mamallapuram (Mahabalipuram) was named. There the famous stone-cut temples, or

raths

, each hewn from a single giant stone, were probably the work of Narasimha-varman II (also known as Rajasimha), who ‘assumed titles galore – about 250 of them’

12

– and reigned from c695-c728. He also built the so-called Shore temple at Mamallapuram, and began the Kailasanatha at Kanchi.

His Chalukya contemporary was Vijayaditya, the grandson of Vikramaditya I and another man of many titles and many temples; most of the structures at Aihole belong to his reign. He also began, but never completed, the first temple at Pattadakal. A level site lying between the twin towns of Badami and Aihole, Pattadakal would under his successors usurp the ceremonial role of both places as the commemorative capital of the Chalukyas. Here during the first half of the eighth century the Chalukyan temples assumed a size and magnificence of ornamentation unsurpassed by anything in contemporary India and rivalled only by the temples of Kanchi. But whereas today the latter are scattered about a large city richly endowed with later architecture, at Pattadakal, always a site rather than a city, the temples now rear up amongst soggy fields of sugarcane where a mud village and a milky cup of tea is the height of modern magnificence.

Two of these temples, parked side by side like vehicles from another planet, were commissioned by two sisters who were the successive wives of Vikramaditya II, he who left his mark on Kanchi’s Kailasanatha temple. Celebrating this victory, the sisters’ twin temples closely resemble the Kailasanatha and so are indisputably of the so-called Dravida style (which climaxes with the great eleventh-century Chola temple of Tanjore). Others, however, both here and at Aihole, show features like the curvilinear

sikhara

(tower) which are distinctive of what used to be called the Nagara or northern style of temple (as famously represented by the later Khajuraho temples). There are also examples of the straight-sided pyramidal style of tower later associated with the Orissan temples, especially of Bhuvaneshwar. It seems unlikely that, as once thought, all these variations were developed by the Chalukyas’ architects. Sculpture and iconography show Gupta influences and imply rather that the far-ranging Chalukyas, in their architecture as in their empire, made of the great Deccan divide a bridge between north and south.

Culturally their Pallava rivals look to have performed the same bridging role between the Indian subcontinent and the Indic kingdoms of south-east Asia. No region or dynasty of India had a monopoly of south-east Asian contacts. We know that Bengal had regular contacts with both mainland south-east Asia and its archipelago; Fa Hian sailed for Indonesia or Malaya from the Bengali port of Tamralipti, and many Chinese and south-east Asian Buddhists reached the great university of Nalanda in Bihar via the same port. Orissan influences have also been traced in Burma and the Indies; failing any better explanation, it is quite possible that ‘Kling’, the name by which people of Indian origin are still known in Sumatra and parts of Malaysia, derives from ‘Kalinga’, the ancient Orissan kingdom. Likewise Kerala and Gujarat seem to have had regular contacts with south-east Asia, which with the entry of the Arabs into the carrying trade of the Indian Ocean would be greatly increased.

However, the most pervasive influence in south-east Asia during the fifth to seventh centuries seems to have been that exercised by the Pallavas of Kanchi. In mainland south-east Asia an important new kingdom had begun to emerge in the sixth century. Based in Cambodia, it would soon absorb Funan, the Indic kingdom on the lower Mekong from which it had probably broken away, and would eventually emerge as the great Khmer kingdom of Angkor. Its kings, like many of those of Funan and Champa (another Indic state in Vietnam), almost always bore names ending in ‘-varman’, just like the Pallavas. More significantly, they claimed descent from the union of a local princess with a certain Kambu whose descendants were known as ‘Kambujas’.

From this word came ‘Cambodia’ and ‘Khmer’. But the Kambujas, as both a people and a place, first occur in the epics and the

Puranas

where they are located in the extreme north-west of the Indian subcontinent, a good three thousand kilometres from Cambodia. It has already been suggested that the sacred geography of the Sanskrit classics tended to get replicated as new regions became Sanskritised (e.g. Mathura, Madurai, and Madura in Indonesia). Kambuja’s improbable removal from the upper Indus to the lower Mekong looks to be another case in point. Moreover the adoption of Kambu as a common ancestor would seem to show how such transpositions might have come about, with kings as far away as

Indo-China laying claim to the legitimacy provided by an adopted Sanskritic forebear. But what is also significant is that this particular myth seems to have been a revision of the story of the brahman Kaundinya and ‘Willow-Leaf’, his ill-clad local queen. And that in its turn ‘shows a certain kinship with the genealogical myth of the Pallavas of Kanchi’,

13

indeed ‘is strikingly similar’ to it.

14

Indo-China apart, the Pallavas are known to have become involved in dynastic struggles in Sri Lanka, to have developed Mamallapuram as a long-distance trading station, and to have had diplomatic relations with China. No doubt commercial, religious and political factors all played their part in promoting a more direct, if still conjectural, Pallavan influence in the south-east Asian archipelago. An inscription found in Java uses the Pallava script and that island’s earliest surviving Hindu temples, small stone-built shrines scattered across the misty highlands of Dieng and Gedong Songo, show clear affinities with the architecture of Mamallapuram.

In Indonesia as in Indo-China important political developments were under way. The eighth century saw the emergence from obscurity of Srivijaya, a maritime power and possibly a dynasty, which would control a seaborne empire stretching from Sumatra to Malaya, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. In terms of national psyche the watery imperium of Srivijaya is as important to modern Indonesia, itself ‘a pelagic state’, as is the continental empire of the Mauryas to Indian centralists. Like Champa and Cambodia, Srivijaya was nevertheless a decidedly Indianised polity, although apparently more Buddhist than brahmanical. Its capital, near Palembang in south-eastern Sumatra, looks to have been the place where in the late seventh century I-tsing (I-ching), another Chinese scholar, found a thriving monastic community. From its monks he received preliminary instruction before proceeding on to Bengal and Nalanda. Returning, he lived with the Srivijayan Buddhists for several years as he worked on the translation of texts acquired in India.