Indian Captive (11 page)

Then a sturdy red hand found her own and gave it a tug. The Indian boy, with swift determination, pulled the girl to her feet. He pointed out the direction and started off. Slowly Molly lifted her feet to follow. He was taking her back to the Indian village and she didn’t want to go. He kept just a step ahead, turning now and again to make sure that she was coming. Each time he turned, he smiled a smile of encouragement.

She hadn’t gone far at all. By the path that the Indian boy took, it was only a short way back to the village. The deep forest was left behind and the two came into the thicket. There at the edge was the spring and the water vessel where Molly had left it.

The boy flung himself down on the ground, made a cup of his hands under the dripping water and drank. Then he motioned to Molly and she did the same. How good the spring water tasted! She was thirsty and had not known it. She washed her face in the water and it felt fresh and cooling.

The boy pointed to the filled water vessel and, obediently, Molly took it up. The water was heavy, but he did not offer to help. He walked on ahead and once more she followed at his heels. Soon they were back at the lodge. Molly set the vessel down and watched the boy, as he ran off toward his home. She watched to see which lodge he entered. She saw him stop beside the door, turn and smile, then disappear from sight.

With a deep sigh, Molly picked up the vessel of water and walked slowly into the lodge.

A Singing Bird

“TELL HER…TO MAKE ME…a cambric shirt, Without any seams…or needlework…Tell her …to wash it…in yonder well…Where never spring water…nor rain ever fell.

L

ITTLE TURTLE, THE

I

NDIAN

boy, heard the faltering words and hurried faster. The new captive girl was singing. She was singing a strange song of the white people. She must be happy today. She had put her sorrow aside at last.

It had not taken Little Turtle long to find out that when the white girl was sent to bring water from the spring daily she ran off to the forest, sat under the walnut tree and cried for hours. He wondered that Squirrel Woman and Shining Star allowed it. Every day he expected to see Squirrel Woman, cross and ugly, march out and with kicks and blows fetch the girl home. But she did not come. Perhaps she knew as he did that the white girl’s sorrow must wear itself out. There was no hurry. As each moon passed, her unhappiness would fade. There were many moons to come. But in the meantime he did what he could.

Day by day he followed Corn Tassel to the woods, and when she had dried her tears, took her by the hand and coaxed her home. Day by day he talked to her patiently in the Seneca language, pointing out objects and repeating their Indian names over and over, in the hope that some day she could speak to him in reply. Surely if she could speak his language she would feel happier in her new home.

Today she was singing. But the sadness, as he came nearer, wrung his heart. The words were happy words—he could tell that by the sound—but the voice that sang was still filled with pain. Corn Tassel! Her name was as beautiful as her hair! If only she could be happy!

Suddenly the song broke off in the middle. Molly looked up. Little Turtle held out a silver brooch. He smiled expectantly. Surely a piece of shining silver cut in delicate design would please any woman or girl-child. “Here! This is for you!” he said.

But Molly did not so much as look at it. She rose to her feet and instead of waiting as usual for him to go first, she ran back to the village as fast as she could go.

With the silver brooch still in his hand, Little Turtle stared after her, shaking his head. He wished he understood her better. If only she could speak in Indian…Deep in thought, he watched her as she ran, then started swiftly in pursuit.

As he approached the lodges, he heard a buzz of excitement. A hunting party which had been out for a short trip was returning along the trail by the creek. Some of the women and children who had gone out to meet the hunters followed behind, laden down with game and dried meat.

But Little Turtle gave no heed. Running swiftly, he caught up with Corn Tassel as she was about to enter Squirrel Woman’s lodge, and took her by the hand. He pulled her along behind him with desperate determination.

Little Turtle approached the largest lodge in the village. He gave a call as he stood before the door. When the answer,

“Dajoh,

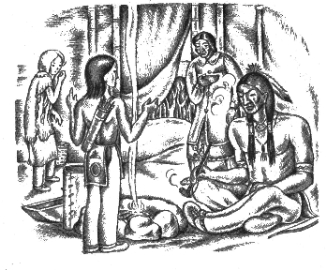

enter!” came, he lifted the flap and went in, pulling Molly along behind him. The boy and girl found themselves in the presence of a group of men who were sitting about a fire. All eyes were fixed on one man, the Chief.

Chief Standing Pine was the most important man in the village. He was strong and handsome, wise and thoughtful. No one entered his presence lightly. He had no time for trivial things. He sat on the ground, with his feet crossed under him. His face was turned toward the fire in quiet meditation. Attentively a woman handed him his pipe and a martenskin pouch. Then she stood behind him, ready always to anticipate his needs and serve him. The Chief nodded his head and the men left the room. Slowly he took tobacco mixed with savory red willow bark and carefully filled the pipe. Little Turtle now ran forward, took it to the fire and laid a hot coal on top of the bowl. Then he handed the pipe back to the Chief.

Molly waited in the corner, staring. She wondered why Little Turtle had brought her there. The room was quiet and nothing was said. She wished she had not come. After a long period of waiting, the great Chief turned to the little Indian boy and the two began to talk. Molly listened, for she knew they were speaking of her.

“What is it, my son?” asked Chief Standing Pine.

Little Turtle, young as he was, knew it was not wise to approach the subject dear to his heart too directly. He would lead up to it by slow, careful steps.

“When a hunter traps a raccoon or a fox, O Chief,” said Little Turtle quietly, “he uses the dead-fall. As soon as the animal eats the bait, the small log falls and kills him at once. Is it not so, O Chief?”

“Yes, my son,” answered the Chief.

“The dead-fall is better,” went on Little Turtle, “than a trap or contrivance which allows the animal to suffer great pain. A hunter should not be wantonly cruel. That is true. Is it not, O Chief?”

“Yes, my son. You are indeed wise for a hunter so young,” replied the Chief.

“A hurt animal in a trap cannot go free,” said Little Turtle. “That is true, is it not, O Chief?”

“Yes, my son. You have observed well.”

“A white girl captive is like an animal in a trap, suffering great pain. Is it not so, O Chief?”

Chief Standing Pine made no answer. Then Little Turtle was bold. To the great Chief, so wise and thoughtful, he made a suggestion. Not many dared be so bold, but he did it for Corn Tassel’s sake.

“Can we not help a poor captive go free, go home to her people?” The anxiety he felt never once broke through the boy’s voice. “If she drowns herself in her tears, is it well to keep her here, O Chief?”

Little Turtle trembled, not knowing what he must suffer for saying such words. The old Chief looked hard at him, then at the white girl who cowered against the wall.

“My son,” he spoke with great patience, “you are too young to understand. You do not know the ways of war. War is a cruel master. War is never kind to the enemy. We take the life of a man only when his tribe is at war with us.

“The pale-faced people come in mighty streams from over the great waters. They come to our forests, our streams, our meadows. They kill our men, they kill the animals the Great Spirit has given us for food and clothing. They spoil our hunting. Their horses and cows eat the grass our deer used to feed on. They have no respect for the forest. They chop down trees, not for use, but merely to destroy them. They build houses where our lodges once stood. They are pushing us out of the lands of our fathers. They come, not as friends, but as enemies, taking from us things that are rightly ours.

“We raid, sack and burn their settlements as they do our villages. It is kill or be killed. We fight for our very life. We take scalp for scalp, captive for captive—no more. Our religion tells us that for every scalp or captive taken by the pale-face, we must take a scalp or captive in return. That is justice. It is the ancient law come down from our fathers, by which we live. These things you will understand and accept as you grow older. You are young, my son.

“It is hard to see the grief of the pale-faced captive. Yours is a noble impulse and I forgive you. But there is nothing you can do. Time alone can help. Time, the destroyer of every affection, will dry the tears in the white captive’s eyes. Before many more moons have passed, the little one with hair like waving tassels of golden corn will be happy. Before many moons, she will forget her sorrows, forget the pale-faced people and be happy with the Indians. I have spoken. Go, my son!”

Little Turtle’s face was as sad as Corn Tassel’s when they came out of the lodge together. He knew the Chief was wiser than all men and he knew his words must be true. Only one thing he did not accept—the thought that there was nothing he could do. He was determined to help Corn Tassel more than ever before.

Although she could only guess what he had said, Molly knew that the Indian boy had been interceding for her with the Chief. She knew that he was sorry for her and she felt between him and herself a bond of understanding. She was filled with a new kind of content when the boy was with her, a content she felt with no one else.

They walked along slowly together. Just when they reached the lodge, Squirrel Woman rushed out in haste, as if she were looking for Molly. She sent Little Turtle away abruptly. Then she brought out Shining Star’s baby strapped to his baby frame. Seizing Molly by the arm, the woman quickly placed the baby on the girl’s back and laid the burden-strap across her forehead. She lifted up to her own back a heavy basket of seed corn. Then she started off to the field, calling to Molly to follow.

It was planting-time, Molly knew. She had seen Red Bird, the older-woman, and Shining Star, the kind sister, go off earlier with baskets of corn on their backs. She knew they were making ready to plant corn.

Molly had never carried a baby on her back before. The baby was about six months old, she guessed, much larger and heavier than her tiny baby brother at home. But she had never dared look at him or touch him. She stayed as far away as possible.

The load of the baby was heavy and the burden-strap cut cruelly against her forehead Molly poked her head forward, stooping to lessen the weight. Then she knew she was walking like an Indian woman. Was she turning her toes in, too?