Indian Captive (7 page)

At the end of the village the Indians halted and Molly, too, was obliged to stop, restraining her impatience.

She stood there in the pathway, looking hard at the fort which she knew held for her either freedom or captivity. Dirty, disheveled, browned by exposure, with her clothing torn to shreds, she shifted from one tired foot to the other, as she stared at the fort. The setting sun picked up glints of light in her tousled yellow hair and shone into her eyes to blind them. She tried to read a message in the cold, hard stockade walls, but they gave no hint of their secret.

Then she saw that the time to enter had not yet come and she must wait. Preparations of some kind were being made by the Indians, so she sat down, doubling her knees beneath her and watched.

The Indians laid a fire and gathered wood to pile upon it. A pole was raised near by, tomahawks were struck into it, and a string of wampum—a belt of beads with design of sacred meaning—was hung at the top. The twelve Indians stood about the fire, smoking peacefully, while the Frenchmen and the three captives waited. The smoke signal seen, an Indian messenger soon advanced from the village. Seeing the peaceful intent of the newcomers, he bade them welcome and the ceremony was concluded, but still the party was not ready to advance.

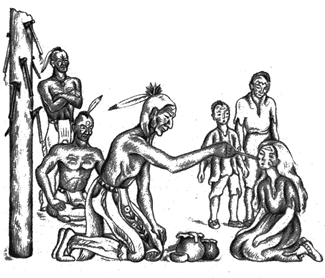

The old Indian, Shagbark, friendly as before, approached Davy and Nicholas and motioned them to sit down. He brought out a crude bone comb from his pack and painstakingly combed their blond hair. He combed out briars and tangles, then shaved their heads clean except for a strip from forehead to neck, which he dressed in Seneca fashion.

Molly’s hair he left hanging loose and free about her shoulders, a shower of shining gold. Then he mixed paint in a shallow stone mortar and with the cloth-covered end of a stick dauber painted broad streaks of red across the captives’ faces.

Molly put up her hands and hid her face in shame. Then she looked at Davy and Nicholas, scarce recognizing them. A strange picture the three captives made—a young man, a half-grown girl, a little boy—their white, white faces streaked with red. What did it mean? What was going to happen? Were they being prepared for something worse?

“All we need now is black hair!” said Davy, bitterly.

“And black hearts!” added Nicholas, with a flash of insight.

“They can change our faces,” said Molly, “but our hearts they cannot change.” She looked down at the red paint which had rubbed off on her hands, and the tears rose to her eyes. They stopped for a moment upon the banks opposite the stockade gate for further parley and the captives watched the two mighty rivers as they flowed into one. There it lay, the great divided river, shining bright and peaceful in the sun. On all the shores the hills were lined with forests—forest trees in the first full burst of tender green. At the river’s edge, the trees grew downward, reflected in the mirror of the silent, peaceful waters.

“The French call it the River Beautiful,” said Nicholas Porter. “O—hi—o! River Beautiful!”

“It

is

beautiful!” exclaimed Molly, watching it thoughtfully. “But how do you know?”

“‘La Belle Riviere,’”

Nicholas repeated to her surprise. “I heard them say it in French.”

“Do you understand French?” asked Molly.

“A little,” replied Nicholas, falling into silence again.

The Indians came to take them into the fort. The walls grew taller as Molly approached. They grew taller and more unfriendly, until she felt they would fall and crush her. For one wild moment she wanted to rush away—anywhere, back to the wilderness, anywhere to get away. She would live in the forest, eat of its roots and berries, be a friend to the wild beasts. Her thought that moment sprang to action and quickly her feet obeyed. Before her masters suspected her intention, away she rushed from their grasp. Round the corner like a whirlwind she dashed on flying feet that scarcely touched the ground.

But her escape was only a vain hope, for stronger pursuers followed close. She felt the jerk of a cruel hand that threw her prostrate and the lash of a stinging whip about her legs. With wild tears falling and body shaking, she was dragged back to the spot from which she had run. There, still standing motionless, Davy and Nicholas welcomed her back with eyes that spoke pity.

Then Molly found herself walking across the drawbridge. Inside the log stockade there was a deep ditch and on its banks thick walls of squared logs and earth rose up. Store-houses, dwellings and barracks built of logs lined the side walls between the tall garrison look-outs. A six-sided stone building stood in one corner. The buildings were bustling with people and a babble of men’s voices, speaking in French, could be heard. All these things Molly scarcely noticed as she entered the fort enclosure, but other things she did.

Certain things, certain little things she saw and always remembered long afterward when Fort Duquesne had faded to a dim and uncertain memory. An outdoor bake-oven and several well-sweeps stood before the row of doorways. A boy carried a pailful of water across the yard. Near a corner, from a log building, two cows put out their heads, mooing contentedly. A Frenchman went whistling past the door, carrying hay on a wooden pitchfork. Beside the barn was a tiny garden where plants and fruit trees grew in rows. One of the trees was a peach tree and because it was April, the tree was in blossom.

Molly’s homesick heart gave a leap as she saw it. Silhouetted against the deep blue of the sky, the beauty of the pink blossoms overwhelmed her. There had been a peach tree long ago beside the log cabin at home, a peach tree that stood so close you could touch the blossoms from the doorstep. She stared at the blossoming tree in the fort yard. She could only stare at it—stare at it so hard she would never forget it. She had no time to touch a pink blossom now, to smell its delicate fragrance. Impulsively she reached out her hand—and saw red paint upon it. She turned quickly, for the sight of it filled her with horror.

Important-looking French soldiers and Indian chiefs in full regalia bustled out of the largest cabin to meet the arriving band. Words passed and the three captives were hustled indoors without delay. They were taken down a damp hatchway into the cellar of one of the garrisons. Bread was brought, the door was closed and locked, and they were left alone.

All night long the captives sat on a hard wooden bench, staring into darkness. They dared not sleep for fear they might be wanted for some unknown purpose. They talked a little, to cheer each other with the comfort of human words. For a time they were hopeful and dreamed of freedom—the happy thought of walking out of the fort without their masters—the thought of home and family, food and comforts. Then they wondered what they could do with freedom if they had it—where could they go if they were free? To the westward and on all sides lay an unexplored wilderness. To the eastward, behind them, were the mountains which they had just crossed. They knew—sane reason told them—they could not go back alone, defenseless, following unknown trails, surrounded by wild beasts. So hope died within them.

Back to their tired minds came thronging all the stories they had heard of Indian punishments and tortures, and they wondered if they’d been brought thus far to suffer such a fate. After a time, Davy began to cry for his mother and Nicholas to talk of his hunting trip. With a heavy heart, Molly took a hand of each in hers and cheered them as well as she could.

Morning came at last. The door opened and their Indian masters entered, beckoning Davy Wheelock and Nicholas Porter to come out with them. Obediently they rose and followed.

Molly walked behind them as far as the hatchway door and watched. She saw that the two boys were turned over to a group of strange blue-coated Frenchmen—Frenchmen like the others who wore lace ruffles on their sleeves. Little Davy looked up inquiring, but Nicholas walked as in a daze.

Their backs turned toward her, without a sign or gesture, Molly watched them go, never guessing it was for the last time she had looked upon their faces. Those dear friends who had suffered with her and looked to her for comfort—if she had known, could she have let them go? But they never knew it was a parting, nor did she, till they had passed without the gate. Then she ran back to the wooden bench, buried her face in her hands and fell sobbing to the ground.

Alone she lay there, but for how long she neither knew nor cared. The loss of her companions seemed unbearable and yet she knew that she must bear it.

She prayed to God for strength and guidance on the long, dark path that lay before her. She repeated to herself her mother’s last words and admonitions and after a while she dropped asleep. She wakened to hear the sound of whispered voices. Looking up, she saw two figures at the door—women’s figures, bunched in clothing; the first women she had seen since she parted from her mother. The light behind them threw dark shadows on their faces and the words they spoke were strange. They stood a while, looking at her keenly, talking to themselves. Then they came closer and she saw that their faces were not white faces but Indian.

The women walked toed-in, bent forward, with shuffling gait. No white woman ever did that. They wore buckskin leggings like men and embroidered moccasins on their feet. No white woman, even in the wilderness, did that. O for the sight of a full-gathered homespun gown with snow-white kerchief and apron! O for the sight of blue eyes of a white woman, eyes of pity and love in a white woman’s face. Would she never see that again?

The faces that came so close and peered so keenly were not white—they were Indian. The eyes that looked out were not blue but brown—dark brown, and they showed neither pity nor love, only cold appraisal. The two women lifted the girl from the ground, set her for a moment upon the bench, then bade her rise. She stood still and let them examine her. Why should she care what happened now? Like a frontier farmer looking over a horse or cow he meant to buy, so they looked her over. Were they about to buy her too? They noted her strength of limb and body, the toughness of her muscles, the firmness of her skin. They pinched her cheeks, they looked into her mouth and counted her even white teeth. They kept nodding their heads with approval, smiling shyly and making low soft sounds.

They seemed to be pleased. But the thing that pleased them most was Molly’s hair—her pale yellow, shining hair, the color of ripened corn. They took it in their hands; they blew upon it and tried to braid it; they let it rest like corn-silk soft upon their palms. They looked at it as if they had never seen such hair before.

After a while they went out, returning again in a moment. This time Molly’s Indian masters entered with them. The morning sun made a streak of light down through the hatchway door—a bright patch in the darkness. The air was filled with words, soft, deep-throated Indian words, spoken with care and deliberation. When the old Indian, Molly’s friend on the journey, spoke, the others listened with respect. Were they making a bargain? What were they talking about?

Soon it was over. Then they all went up the steps and out once more to sunshine. They walked out from the fort enclosure. But before the great log gate swung to behind them, Molly caught one glimpse of the blossoming peach tree, the tree that had bloomed for her. She saw it standing not where it really was, but close beside the door at home.

Then she was out on the river banks and she saw two bark canoes drawn up close to shore. Her former masters, the old Indian with them, took their places in the larger canoe; the two women and Molly in the smaller. Not till then did the girl realize that she had changed masters. It had been a bargain. She belonged no more to the men who had brought her over the mountain, but to the women in whose canoe she rode.

The paddles made soft, gentle sounds as they were lifted up and down, the small canoe following in the wake of the larger. Behind, the gray, cold stockade walls of Fort Duquesne grew smaller and smaller, till the fort was only a dark spot in the distance and that, too, faded away. Ahead lay the wide expanse of shining water, the great River Ohio, the River Beautiful.

Where were they taking her?

Molly sat up straight and tense. She grasped the sides of the canoe with her hands. She lifted her chin and looked ahead. For, through her terror, she heard her mother’s voice, saying: “Have courage, Molly, my child, be brave! It don’t matter what happens if you’re only strong and have great courage.”