Indian Captive (26 page)

Molly put her hand to her mouth and choked back the tears. She kept staring at the canoe while Shagbark removed the frame of branches. She saw him pick up the canoe and drop it lightly on the water, but she scarcely realized what was happening until she heard Shagbark speak.

“Step into the canoe, my son,” said Shagbark to Running Deer. “The canoe is yours!”

“Mine?” cried Josiah, his eyes sparkling. “You don’t mean that I can go where I like in it? I thought a male captive was not allowed to leave the village.”

In answer, Shagbark silently handed the white boy a paddle.

“May your canoe carry you safely over rough waters and take you wherever the Great Spirit may lead you!” said the old man, solemnly.

“Oh, Josiah!” cried Molly, torn between happiness over this unexpected good fortune and Uncertainty over its possibilities. “Then you’re not going trapping with the little boys after all, to take raccoons and a fox or two?”

But Josiah did not answer.

With a smile on his face and a firmer set to his shoulders, Running Deer stepped into the canoe and shoved off. He lifted the paddle high over his head for a moment in farewell, then began paddling upstream.

Molly watched him go with a sinking heart. She wished that she understood him better. Would he be loyal to Shagbark’s trust or would he run away now that spring was coming? Was there a new brightness in his eyes, a new glint of determination? Would he debase the beautiful gift of the canoe by using it to help him on his return to Virginia? Was Shagbark suspicious or innocent of Running Deer’s intentions?

Molly took one last look at the straight figure in the canoe as it rounded a bend. Then she turned to Shagbark. She looked up at him, but she did not need to speak. The old man knew her thoughts.

Shagbark put his hand on her shoulder. “Do not fret,” he said gently. “Running Deer may be trusted. He will return. He will be more apt to return if he is not confined too close. We have not done wisely to keep him close like an animal caught in a trap.”

“Oh, are you sure?” begged Molly.

“I am very sure, little one,” said Shagbark. “He will return.”

Beaver Girl came running. “It is time to go, Corn Tassel,” she announced. “Squirrel Woman is very angry because you are not ready.”

Snow still covered the ground and except for the warmth of the midday sun, it might still have been winter. In front of her lodge, Red Bird was rolling up dried meat and packing it on sleds for the journey. The other women in the village were doing the same. Gradually they all assembled in front of Panther Woman’s lodge and waited.

Panther Woman gave the signal and they started off in the direction of the maple forests, accompanied by a few men and boys. Some of the women pulled the loaded sleds, others carried the younger children in baby frames or pack-baskets. Storm Cloud, Star Flower, Woodchuck, Chipmunk and all the other children ran ahead, skipping and shouting happily.

With Blue Jay in a pack-basket on her back, Molly trudged slowly along behind the others. Despite Shagbark’s reassuring words, her heart was very heavy. Each step was taking her away from Josiah, She knew she could not go on living with the Indians after Josiah went away. His coming had changed her life entirely and given her the first real happiness she had had since Marsh Creek Hollow.

Beaver Girl left the others and waited to walk beside Corn Tassel. Beaver Girl had her baby sister, Little Snail, in a baby frame on her back. She walked quietly and did not speak. She knew that when the white girl captive had tears in her eyes she was thinking of her white family far away, and Beaver Girl was sorry. From time to time she glanced at Corn Tassel hopefully, but the white girl did not look up or smile.

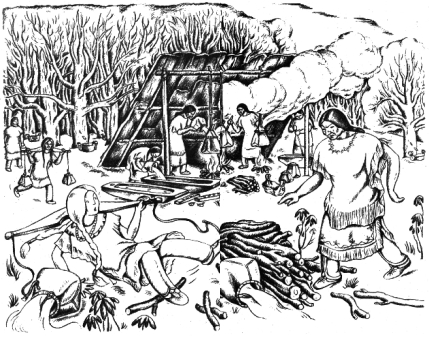

After a journey of several hours the women and children reached the sugar camp. In a clearing at the edge of a fine grove of maple trees stood a few bark lodges. The women and children crowded into them, first clearing out great piles of snow and dry leaves. Here they were to stay for the length of the sugar season.

The party set to work at once. Before nightfall maple trees had been felled and several logs hollowed out by the men, making troughs to hold the freshly gathered sap. The women washed and mended all the bark vessels left in the sap-houses from the year before.

The next morning the work was continued. With crooked sticks, broad and sharp at the end, the women stripped bark from a felled elm tree and made many new boat-shaped vessels, each holding about two gallons. The men notched the maple trees with their tomahawks, driving in long hardwood chips to carry the sap away from the trees. The children ran back and forth setting the bark vessels at the bases of the tree trunks to catch the flowing sap.

Each night the ground froze hard and fast; each day the sun was warm enough to melt it again, and so the sap flowed freely. Drop by drop it filled the vessels. Each day’s run had to be carried to the camp.

Molly and Beaver Girl put wooden yokes on their shoulders and worked with the women, trudging over the hard frozen crust of the snow. They took empty vessels out and carried the heavy filled ones back, emptying the sap into the log canoe troughs by the fires.

Great clouds of white steam poured out from under the bark shelter where the hissing sap boiled furiously, filling the air with a delicious fragrance. Squirrel Woman and Red Bird kept the pots well filled, stirring to prevent their boiling over. Other women made frequent trips to the woods for firewood and kept feeding the fires. When the syrup was boiled down, the women tested it upon the snow, dipping it out with wooden paddles. When it was of correct thickness, they poured it, still warm, into a trough and pounded it with a wooden paddle until it turned into sugar. Part of it was poured into wooden molds and set aside to harden into small cakes.

As the days passed, one exactly like the other, Molly worked impatiently, for she wanted only one thing—to get back to the village to see Josiah. The work was hard and the yoke was heavy. Every day it seemed to cut more deeply into her shoulders. Would this endless sugar-making never be over? Her feet became so tired she could hardly lift them.

Once while passing the wood-pile she stumbled over a loose branch and fell, spilling her vessels of sap on the ground.

Panther woman came running up and scolded her for carelessness and wastefulness.

“Corn Tassel has no eyes in her head!” the woman cried out, in hot anger. “She walks with the blindness of a bat!”

The words lingered in Molly’s mind as she hastened out again to the forest. On her way, she noticed the foot tracks which the party had made in the snow upon arrival. No fresh snow had fallen to hide them.

“I will show her that I do have eyes in my head!” said Molly to herself. “I will show her that I care not how much sap I spill and that I can find my way back to the village alone.”

Dropping her yoke and sap pails, she started off at once. She had gone but a short distance when she heard the sound of footsteps behind her. Looking back over her shoulder she saw with irritation that it was Beaver Girl. On she ran, faster and faster, but no matter how fast she ran, the Indian girl came closer and closer. At last, out of breath and tired, she sank exhausted to the ground. The next moment, Beaver Girl’s arms were around her.

“Do not go, Corn Tassel,” begged Beaver Girl. “If you go back to the white people, I shall never be happy again. I will have no one to talk to, no one to work with, no friend to love. Stay with me, Corn Tassel and be my friend.”

Molly could not tell Beaver Girl what the trouble was, but she was touched by the girl’s friendship. It was true, they were just of an age, and there were no other girls their age in the whole village. Beaver Girl wiped the tears off Molly’s cheeks with her sleeve, then helped her to her feet. Arm in arm the two girls walked back to the sugar camp. They came just in time to see Shining Star dropping thick ropes of hot syrup on the top of a clean bank of snow to harden. They joined the shouting children in the scramble to fill their brown fists with the delicious candy and to stuff their mouths full.

At last all the sugar was made and it was time to go back to the village. In three weeks’ time, a supply large enough to last a year had been made and packed in bark cones for storage. The sleds were reloaded and they left the sugar camp.

The air was soft and sweet on the day when the party returned to the village. Only a few patches of snow were left in shady spots in the forest. Robins and bluebirds were singing, hopping from limb to limb, but Molly had no eyes to see or ears to listen. She was thinking of only one thing—Josiah.

Immediately the village became the scene of turmoil and excitement, for the bringing of the maple sugar must be celebrated with a festival of thanks to the maple. The men had returned from the fur-hunt, so the women hurried to prepare an elaborate feast and soon had huge pots boiling. The people sat down in the open space in front of the lodges and listened to speeches given by the keeper of the faith and other important men. Then Chief Burning Sky scattered sacred tobacco on the great central camp-fire and gave a song of thanks to the Great Spirit. He said:

“We thank thee, Great Spirit,

For sending the soft winds and fair breezes

To melt the snow

And make sweet waters flow

From the heart of the Maple.

“We thank thee, O Maple,

For thy sweet gift

To thy children

Who roam in the forests—

We thank thee,

We thank thee, O Maple!”

During the dancing and feasting which followed, Molly looked for Josiah but could not find him. She ran to Earth Woman’s lodge, but when she saw a sweetfern broom propped up to hold a bark slab over the door, she knew no one was there. Then she looked for Shagbark and wondered at his absence. With a feeling of uneasiness, she kept watch on all sides, but neither Shagbark nor Josiah appeared.

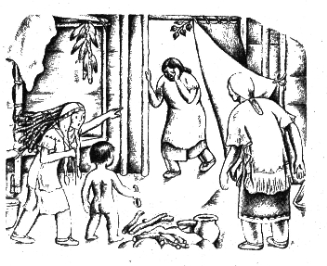

Not till the day after, did Molly learn what had happened. Before the fire was laid in the early morning Earth Woman ran into Red Bird’s lodge in frantic haste. Molly dropped the load of wood she carried on her back and ran to meet her.

“He is gone! My son, Running Deer, is gone!” cried Earth Woman, overcome with grief. “He has gone back to the pale-faces. I have hunted for him all through the night and I cannot find him.”

Red Bird’s family and all the others from the adjoining rooms crowded up to hear.

“Shagbark missed the canoe three suns ago,” Earth Woman went on, “but Running Deer may have gone before that. When the boys returned from their trapping, they said he had never been with them at all. Oh, we should have kept closer watch; I should never have gone to the sugar camp…He knows the forest like an Indian, he runs as swiftly! He should not have been given a canoe to speed him on his journey…”

“Is it wise, then,” cried Molly, indignantly, “to keep a captive bound too close? A strong animal caught in a trap will break it to pieces and flee!”

“Hush! Hold thy tongue!” said Red Bird, severely. “Corn Tassel has not been asked to speak. Even when all have spoken, she shall not be asked to speak.”