Indigo (40 page)

Authors: Clemens J. Setz

â Oh, Herr Setz! Thanks for calling back. I hope I'm not interrupting anything important.

â No, at the moment I'm in . . . Oh, never mind. What can I do for you?

â Are you sure that I'm not bothering you? Are you out at the moment? Or in another country?

â No, everything's okay, I'm at home.

â Are you sure?

â Yes, I'm sure.

â Okay, she said. At home. Yes, well . . . I just wanted to tell you that everything went smoothly.

â What are you referring to?

â Oh, Herr Setz, she said with a giggle, as if I had made a joke. Well, you can certainly imagine what a transfer like that means for a young person like Christoph. He's inwardly so peculiar, you know. He's not like other people, he's more like a landscape, I mean, deep inside, sometimes he seems to me like one of those warehouses big companies have, you know, IKEA or something like that, those vast buildings along some streets that all lead out of the city, built-up areas, where you find no sense of security, no point of reference, except maybe a few grassy strips, you know? Like those little green islands between parking spots. But apart from that . . . just cavernous buildings and dirty wet steel and industrial waste on forklifts and so on, like in the opening sequence of that terrible, gloomy Russian science fiction movie, my God, I saw it once years ago, and since then I've always been afraid I'll suddenly stumble into it again one night while channel-surfing. I usually change the channel immediately when I come across a black-and-white movie and don't immediately recognize the actors.

I again poured water over my head. As I did so, I had to lift the cell phone a bit, so that it wouldn't get wet. The characterization of Christoph's inner life had flustered me. Once again I had the sensation of having heard a prepared statement, like that of a bought witness in court. And a sentence from Josef Winkler's first novel crossed my mind: I am devoid of people. The moment when a being actually ceases to feel inhabited and populated by others, and that frightening point in history when it became clear to people that they didn't bear homunculi within them, that the man doesn't implant in the woman microscopic copies of himself in his seminal fluid, which then grow with their limbs in constant proportions. What must this sudden realization have felt like, that we're inhabited by aliens, bacterial cultures and skin mites, which feed on dead flakes and cells and, like faithful janitors or groundskeepers, roam around all day on a tiny area of skin, which is probably not much larger than a postage stamp, and do their mechanical grazing work? I thought of the debate in Swift's

Gulliver

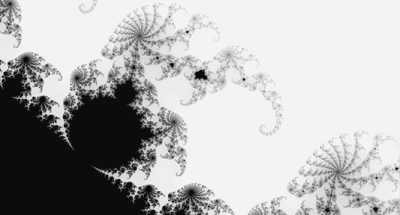

, in which scholars of the court of Brobdingnag, the land of the giants, debate whether this little person they have found in a field is a sort of automaton, a piece of clockwork without a soul, which has been taught language, or actually a human being. If I remembered correctly, despite Gulliver's ability to interact intelligently with the scholars, it was only by the measurement of his limbs that the matter of dispute was decided in his favor. I looked at my foamy hand, from which drops of water fell. And hadn't the doctor Sir Thomas Browne in the seventeenth century mentioned in a treatise his strange shudder when, while dissecting a brain, he discovered a convolution thatâsimilarly to how the man in the moon has been perceived for centuriesâwas even without much imagination reminiscent of a tiny human figure, a sort of secret, no-longer-needed construction manual for the whole, which lay dead before him on the operating table? He must have wondered whether his brain didn't also contain a form like that, which at that moment performed exactly the same movements (the cutting, the severing of tissue, the holding, turning, and studying in the light) as he did, and perhaps for this incredible feat it required in turn a smaller version of itself, and so on and so on into eternity, a fractal process as with Benoît Mandelbrot's holy set, which after a long, long deep zoom through the fringes of its valleys and lakes and islands shimmering in various colors keeps presenting itself to us, wonderfully preserved in its tininess and identical with the whole, an infinite series continuable in both directions.

â Hello? Are you still there?

I looked up. In the steamed-up bathroom mirror someone had left a message in finger writing. But it was too blurred and too misted over to remain readable. Magic slate.

â Yes, I said. What? Um, it's only water. Keeps the brain alert.

Frau Stennitzer made a noise as if she were sucking on a cigarette. Then she coughed and said:

â Yeah, water is necessary for . . . But Herr Setz, am I really not bothering you?

â No, I said, I'm just in the bathtub at the moment . . . I like to take baths, you know.

â Ah, I see. Yes. Of course. You're in the bathtub. Well, then I don't want toâ

â No, you're not bothering me. You were just about to tell me about your son, and then I . . . I was distracted for a minute.

The water I was constantly pouring over my forehead made the headache a little better, but when Frau Stennitzer began to speak, it came back. A sun that was waiting behind the mountain ridge and could suddenly rise at any moment. I closed my eyes and tried to focus. I saw fractal swirls, the seahorse valley. Males who get pregnant and release tiny copies of themselves into the world. Sons, planets.

â Yes, well, said Frau Stennitzer, that's why I'm calling. Christoph says hello, he really bears no grudge against you, Herr Setz. And the articles, well, that was quite a while back, right? Yeah, and . . . I just wanted to tell you that you're always welcome to visit me and that you don't have to worry. True, I don't want to skirt the issue, Christoph has had his problems with the transfer, of course, he is reaching that age, after all, but I think, despite everything, it wouldn't be fair if I hadn't tried it, right?

â Yes, I said.

I didn't have the faintest idea what she was talking about.

â You know, recently he has often gone for long walks. And then I've kept telling myself that I don't need to worry, that he's doing fine, wherever he has retreaâwherever he is. He likes nature a lot. And the few visits to the swimming pool back then, I mean, okay, that was probably simply a sort of retreat. I hope I'm not boring you, Herr Setz?

â Excuse me? I was just . . .

I splashed a bit in my bathwater.

â Well, I certainly don't want to bore you, Herr Setz, the last thing I'd want would be to rob you of your precious time, which you must need for . . . for writing and researching and whatever you do when you're working on your nextâ

â Hey, may I ask you something?

â Go ahead.

â It's a bit unpleasant for me to ask you, of all . . . I mean, this isn't meant to sound offensive, now, but . . . do you by any chance know a good remedy for headaches? I mean, you must, of course, have . . .

â Have experience with that?

â Oh, this is really stupid, I'm sorry.

â No, Herr Setz, not at all. It's not stupid at all. I have in fact tried some things. What sort of headache is it, then? With dizziness?

â Yes. A little bit.

â And what's the dizziness like? More spinning or just a feeling of disorientation . . . or is it a more deep-seated dizziness, less in your sense of balance and more in your core, in a way? I'm sure you know what I mean.

â More the first kind.

â Just spinning?

â Yes, when I lean back. Plus this splitting headache.

â And you're alone?

There was a pause. She hadn't asked this question in a different tone than all the others. Objectively interested. A woman who knew what she was talking about.

â So for

that

, Herr Setz . . . well, for

that

. . . there's nothing. Nothing that springs to mind. Besides painkillers. A massive amount of painkillers. But they usually don't make the symptoms go away.

â Okay, I said.

â A massive amount of painkillers. One after another, stacked into a pyramid. But be sure to leave sufficient intervals between the individual pills. Or else there could be a misunderstanding in your body.

â Thanks. I'll tryâ

â Something else occurs to me. A change of locale, maybe? That also does good sometimes. Go north. The nights are more pleasant there. I can't do that, unfortunately. I always have to stay here.

â Residenz Verlag, I said softly.

â Pardon me? asked Frau Stennitzer.

â I said, Re . . . Oh, I'm sorry, something just crossed my mind. A little disrupting signal, so to speak, an interf . . . um, you know what I . . .

â Yes, you make a confused impression, Herr Setz, she said, and hung up without saying goodbye.

10.

A Peculiar Network

Robert felt as if he had drunk thick syrup through his eyes. To cool off, he stared at a harmless stain on the wall. A mark that had nothing to do with him and the rest of the human world.

He had read through the contents of the folders almost in their entirety.

Magda T., peaceful use of Indigo potential, Oliver Baumherr, Ferenz.

Even when he closed his eyes, the terms stood before himâthe same effect that set in when you stood in front of the magnificent empty iSocket on Annenstrasse, in the middle of the night, when up in the sky only few stars and down on the earth only few lights were scattered about.

The telephone book seemed pleasantly surprised that, after so many years of total disregard, he was consulting it for the second time in a few days. It chirped softly and continuously while he searched for the name.

Hofrat Prim. Univ-Prof. Dr. Otto Rudolph.

Robert couldn't help laughing. He imagined biting off the title jutting out over the man's name like a protruding cellophane wrapper. Like when you take a candy cane out of the wrapper and nibble it down to a small stump, and then you put the stump back in the wrapper. Or like a much-too-long foreskin.

Robert slammed his fist down on the floor. The telephone book chirped and recoiled a little.

In his room he looked for the most

Matrix

-like coat he could find in the wardrobe. And sunglasses. It was an overcast day, but whatever.

It's 106 miles to Chicago, Robin, we got a full tank of gas, half a pack of cigarettes, it's dark, and we're wearing sunglasses.

He briefly thought about taking his Darth Vader helmet with him, but he left it in the wardrobe.

When he stepped onto the street, it was just beginning to rain.

On his way he ran into a festive parade made up of twenty to thirty people, who squeezed through a narrow side street. He saw the people equipped with horns and colorful flags from some distance. They were coming toward him. He immediately turned around, ran out of the side street, and for the rest of the way stuck to main roads.

The doorman wrote down Robert's name very carefully, and the iBall over him in the little booth looked frightened and paranoid, like an animal kept too long in a cage. Robert waved to it. No reaction.

A phone call was made, intercoms were spoken into. A little key was even in proper James Bond final boss fashion stuck into a lock on the desk and turned. Then he was let through.

Dr. Rudolph had grown quite old. But he greeted Robert warmly and with genuine surprise. He immediately asked him what he was doing these days, but then corrected himself right away, he had of course, obviously, heard about the award, the prize for the painting, oh, that was really wonderful, to become aware from time to time of the late fruits of his efforts. The institute was, since Riegersdorf had

totally taken off

, unfortunately a thing of the past, but still, he was always happy to hear from his former protégés.

â But please, please, come in, Herr Tätzel.

Robert stepped inside the room and looked around. If he had been wearing augmentors, the room would most likely have exploded into a sea of blossoms made up of price tags. It would probably look like a butterfly house during mating season.

â I thought I'd stop by.

â Yes, oh, that's really very nice of you, Robert . . . Herr Tätzel, sorry, I'm mixing up the time periods.

The old principal laughed. He seemed honestly moved.

â Have you heard, asked Robert, also smiling, about Setz?

The joy remained in Dr. Rudolph's face, but it required some load-bearing wrinkles.

â Ah, he said. Yes, a tragic affair. I'm glad that he didn't stay with us. Well, all right, now he's free. They couldn't prove anything. But the signs were there. The circumstances. The clues.

â He claims that he met someone in Brussels. A man named Ferenz. And I remember that at the instituteâ

â Would you like some coffee, young man?

â No, thanks. Iâ

â Are you sure? I can ask Adelir to make you one.

The principal put his hand to his neck and pressed. A cow-eyed man with a dark beard immediately appeared.

â We'd like some coffee.

The cow-eyed man nodded and disappeared again.