Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (31 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

There was quite a bit of sartorial

gengsi

, of showing off, at the wedding. Tesi’s mother and I were the only two women wearing the traditional sarong kebaya – a long, fitted tunic over a sheet of batik, carefully pleated into an ankle-length skirt and held in place with an elasticated corset. All the other women were trussed up in ‘modern’ kit. The bride wore a tiara and a Western-style wedding gown in white satin with a silver lace overlay. There were long gowns in apricot chiffon, polkadot dresses with puffy bolero jackets, a lot of leatherette handbags. One wizened granny who had long since lost her teeth wore a sequinned Spandex top over a tulle skirt that fluttered well above the knee. She twirled alongside the

cakalele

war dance, led by the more important men of the village who used palm fronds in place of swords, until trickles of sweat traced brown pathways through her rice-flour face powder.

Later, after the wedding, I sat on the floor of Tesi’s living room, chatting with her for the first time. ‘What’s your name?’ she asked. I had shared a mattress with this woman’s daughter for two nights now. I had washed clothes at her well, grilled fish with her husband, worked in her mother’s kitchen and been to her brother’s wedding. And she didn’t even know my name. It somehow made her hospitality all the more gracious.

Tesi was a middle-school teacher. She seemed ambivalent about education in general: her nine-year-old son had not been to school for over a week simply because he didn’t want to. She had tried to put his maroon school shorts on him one morning but he had thrown a tantrum and run off. She immediately gave up, saying only: ‘Boys. What can you do?’ There was no question of her giving up her civil service position, but she complained that her job was boring as well as poorly paid. Almost all Indonesian teachers complain, with very good reason, about how little they are paid. Most do other jobs on the side – take in laundry for example, or run a coffee shop. I asked Tesi if she had thought about setting up a business. Like what? she asked. Well, I said, within a year or two there would be at least 6,500 workers at Weda Bay Nickel. And there were only two food stalls in town, both closed in the evenings. She finished teaching at noon each day. How about opening an evening food stall?

She considered this for a while, then shook her head. ‘

Nanti capek

’: too tiring.

Tesi’s verdict made me think back to Mama Lina up the volcano in Adonara, and the casual expectation of bounty implied by her stab, toss, kick, stab, toss, kick approach to planting maize. The deeply rooted village populations of Indonesia have always lived fairly close to subsistence and millions remain contented with that life.

Those with more ambition have tended to move to the city or to another island to seek their fortune. These people, including the salt-fish ladies of Buton, the nasi Padang cooks of West Sumatra, and aspiring professionals like my friend Anton the

ojek

driver from Flores, are collectively known in their new homes as

pendatang. Pendatang

translates literally as ‘a person who has arrived’, though Indonesian friends offer alternative translations that range from ‘guest’ to ‘invader’. These are the savers and planners, the people who work hard and invest thoughtfully in education or a little business, in things that will improve the prospects for their family and their kids. The millions of Indonesians who embody middle-class values, in other words.

Now, suddenly, the wealth that lies under Indonesia’s skin and that sprouts from its fertile soil is catapulting villagers in places like Lelilef into the ranks of the middle classes, at least according to the World Bank, which rules a line through an income level of US$2 a day and labels everyone above it ‘middle class’. Villagers in some very out-of-the-way parts of Indonesia have, in the commodities boom of recent years, earned well over two dollars a day for palm oil, rubber, copra, cocoa, nutmeg, cloves and other plantation crops. Others have sold their land to mining companies. But their new wealth does not always come with save-and-invest values.

‘Look! Look at her!’ sniffed my neighbour on the cake production line as we prepared for Tesi’s brother’s wedding. She was a hefty woman with just two teeth, one blackened by betel, the other gold. She jutted her chin towards a younger woman who had casually stretched her arms forward so that everyone could see the new-model cell phone she was playing with. ‘See that? They sell all their land to the company and get a chunk of cash all at once. They build a flash house, fine. But then they buy five motorbikes on credit. One family. Not just any motorbikes mind you, smart ones that cost twenty million. Then three cell phones each. And in two years’ time they will have nothing to eat and no land to grow anything on and debts still to pay. Then what?’

At the time of my trip, the Indonesian government was behaving not unlike the villagers of Lelilef; raking in money from commodities, living easy and spending large, though not on anything that contributed much to economic growth. Then what? It seemed like a question that pinstriped researchers at banks in Hong Kong, committees of think-tank worthies, or foreign journalists might be asking. But they were, at the time, busy heaping Indonesia’s economy with praise.

The economic pundits waxed lyrical about Indonesia’s ‘demographic dividend’ – the bulge in the young working-age population, which looks great on a computer screen in Hong Kong or Jakarta. In theory, young households save up and banks lend those savings out to new businesses. More young workers means more people making things, ergo more wealth. In practice, though, a third of young Indonesians are producing nothing at all, four out of five adults don’t have a bank account, and banks are lending to help people buy things, not to set up new businesses.

*

One of the think-tanks, McKinsey Global Institute, was so excited by Indonesia’s prospects that it bypassed the middle class and its save-and-invest values entirely, suggesting that the country would get rich through shopping. ‘Around 50 percent of all Indonesians could be members of the consuming class by 2030, compared with 20 percent today,’ the management consultants said in a report that was immediately trumpeted across the newspapers. That would add 85 million New Consumers – people with net incomes of more than US$300 a month – to today’s 55 million.

McKinsey consulted ‘many experts in academia, government and industry’ for its report: nine Indonesian cabinet ministers, a couple of ambassadors and another seventy-five economists and captains of industry. I wondered how many of them had ever seen what the demographic dividend was delivering in villages like Lelilef.

*

Drake,

The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake

, p. 96.

*

It shared the deal with the Japanese firm Mitsubishi; a bone of 10 per cent of shares was thrown to the Indonesian state mining company.

*

2012 figures indicate that three in ten Indonesians aged between fifteen and twenty-four are neither in education nor working, even informally. Over 6 million Indonesian high-school graduates are currently unemployed; many companies find them unemployable. Companies say that close to half of the ‘skilled’ workers they do hire don’t have the critical thinking, computing or English language skills they need to do their jobs well.

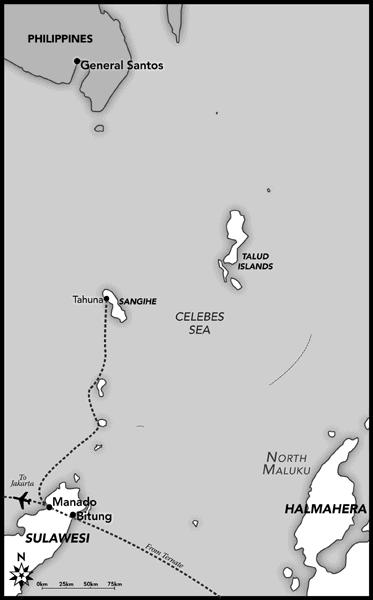

Map H: T

HE

S

ANGIHE AND

T

ALUD

I

SLANDS

, North Sulawesi

I love frontier towns. There’s always something slightly shifty about them, as if nothing is permanent, as if everyone is wheeling and dealing. Tahuna is such a place. It sits on the island of Sangihe, one of the lumps that arc upwards from the north-eastern limb of Sulawesi, and of all Indonesia’s towns it is among the closest to the Philippines. It’s been infiltrated with things from its brash northern neighbour: motorcycle rickshaws fitted with huge boom-boxes and blinged-up stickers of buxom blondes, Coca-Cola in giant glass bottles, pop-tarts with fluorescent fillings. There’s less of the torpor that one often finds on small islands.

I unfolded myself after a cramped ferry ride and set out for a stroll along Tahuna’s sea wall in the golden light of evening, admiring the fishing boats that dot the harbour, each painted in its own distinctive strip, pale blues, bright oranges, sea greens, lots of white. The boats, big and small, have V-shaped hulls, long and narrow, flourishing into an elegant curl at both prow and stern. On either side are bamboo outriggers, hanging off lanky struts that straddle the hull. On land, these give the boats the look of long-limbed grasshoppers; at sea they are more colourful versions of those water-skimming insects that flit over the surface of ponds on still summer evenings. I thought it might be fun to go out in one for a day.

I kicked a football about with a couple of kids, chatted for a while to a priest who was full of ill-focused indignation and alcohol, and wondered idly about the bank of grey thunderheads that had appeared out of nowhere and was massing in the sky like a rugby team getting ready for a scrum.

Minutes later, with the now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t suddenness of tropical downpours, the heavens opened. I dashed into a kiosk above the esplanade, but I was already soaked. Spray pounded up the bank, blustered through the opening in the bamboo weave of the kiosk wall, misted everything in salty dampness. The kiosk owner, another Elizabeth as it turned out, motioned me to a dryish corner and slapped down a steaming glass of tea – ‘Here, this will warm you up’ – and a dish of Christmas cookies, left over from the celebrations of a few weeks earlier. They were little lumpy crescents of crumbly pastry and nuts, flecked with orange peel and dusted with icing sugar, absolutely identical to the Christmas cookies my grandmother made every year until her death in 2004. A wave of nostalgia swept me close to tears.

Ibu Elizabeth and I chatted for a while about this and that – her dead husband, the price of oranges, the dangers of overdoing the spices in Christmas cookies. She thought that maybe she and my grandmother, born a century ago and 15,000 kilometres away, shared recipes because they shared a religion. Then her son wandered in. Jongky was probably in his early thirties. He stood bare-chested in front of the gap in the wall that passed for a window, silhouetted against the storm, his spiky hedgehog hair ruffled back and forth by the wind. While he chatted, he wrapped strong, clear fishing twine around a smooth wooden donut the size of a hubcap. On the end was a hook not much bigger than a crooked earring.

I asked what people around here fished for. Tuna, said Jongky, in a ‘what else is there?’ sort of way. What, with that thing? I had thought tuna fishermen were either Hemingway wannabes in speedboats with strapped-in rods, or the crew of vast long-line factory-boats, carelessly hauling in strings of dolphins as collateral damage. But Jongky and his friends fished off two-man outriggers, sheltered from merciless sun and driving rain by nothing more than a small tarpaulin. The front of the boat is a covered coffin into which, with luck, the fishermen will load the tuna they catch – yellow-fin mostly, or big-eye. Though the outriggers look like balsa-wood models, there’s space for three fish, each up to one and a half times my weight.