Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (34 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

*

A 2011 study of nearly 12,400 businesses in nineteen provinces showed that businesses in Eastern Indonesia had to deal with electricity cuts on average four times a week and water cuts twice a week. In Western Indonesia, shortages were still reported universally, though only half as frequently. See Asia Foundation, 2011.

*

Fuel prices were raised to 6,500 rupiah a litre in June 2013, around 65 cents at the time, saving the government about $1.3 billion a year. At the time, the World Bank estimated the government would still have to pay $18 billion a year in fuel subsidies. The rupiah has fallen dramatically since then, sending the bill for subsidized fuel even higher.

*

This provision is still taken quite seriously. In 2004, for example, the Constitutional Court struck down a law that would have allowed for the privatization of electricity plants, arguing that the state must retain control and manage the power sector for the benefit of all Indonesians.

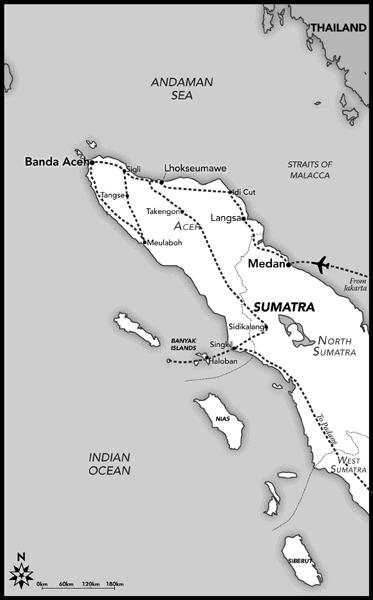

Map I: A

CEH

My first day back in Jakarta, I went to the opening of an exhibition by Renjani Arifin, an artist friend who was showing her new sculptures. The gallery was in a cool, marbled mall, a place where I once used to spend as much on a set of underwear as I now spent on a month of travel. In the gallery, seven-year-olds were playing with hot-off-the-press iPads, and the bohemian glitterati of Jakarta wandered about with glasses of wine, air-kissing one another and cooing at ambiguous stone statues of naked girl-women holding teddy bears and gazing wistfully at an untouchable universe. One beautifully curated woman complained that it had taken her nearly an hour to come from Pondok Indah, an eruption of McMansions just a kilometre or two away. And you?

‘Sangihe,’ I said. The woman looked blank. Like many Indonesians of her class she had been to Paris and New York, to Melbourne and Bangkok, but in Indonesia itself, she had never ventured out of Java and Bali, never heard of the Sangihe islands. I began to describe the life of a fisherman on a two-person outrigger, then saw her eyes glaze. I realized with a heavy soul that I had become one of those slightly earnest foreigners who has gone native. I shut up.

The sculptor’s brother Luwi extracted me and bundled me off downstairs to inspect a cup-cake stall run by another friend, Nungky. He bought three cupcakes for 45,000 rupiah. Everywhere in rural Indonesia, a cake costs 1,000. None of them is piled up with pink and purple swirls of buttery icing like these ones; none is sprinkled with little silver sugar-stars. But still, if he were in the States and paid the same amount compared to average wages, Luwi would have just shelled out US$400 for three cupcakes.

Nungky, an architect who owned the cake stall as a side venture, happened along. She had a fantastic new hairdo, a two-tone look dyed half white, half black, shaved up one side of her head, angled radically down on the other side. With her was Dotti, a documentary producer, dressed principally in electric-blue Lycra leggings. Over the leggings ballooned a batik top, perhaps a bit long to be called a jacket, but certainly too short to qualify as a dress. One arm was crooked outwards to provide a perch for a puff-ball handbag, white leather petals flapping in all directions off a central globe.

I tried to imagine what the salt-fish ladies of Adonara would make of Nungky and Dotti. But of course they would never see the Lycra leggings. If Dotti went to make a documentary about Butonese fishing communities in eastern Indonesia, she’d doubtless morph into a NGO/researcher/anthropologist lookalike complete with khaki trousers and black backpack.

If I felt out of place in Jakarta, it was because I hadn’t morphed quickly enough back into nice underwear and air-kissing mode. It seemed like a huge mental effort to switch back to someone more recognizably ‘me’ just for a thirty-six-hour interlude between a dormitory ferry in northern Sulawesi and a fourteen-hour bus journey in northern Sumatra.

After the Jakarta interlude, I headed for Aceh, the province that sits on the northern tip of Sumatra, the giant island on Indonesia’s western flank. It was election season in Aceh – the governor’s job was up for grabs, and there were also polls for most of the province’s bupatis and mayors. An acquaintance of mine, a human rights lawyer who had studied in the US named Nazaruddin Ibraham, was running for Mayor of Lhokseumawe, halfway up the east coast. He invited me to witness his campaign.

I bought a couple of silk scarves that I could use to cover my head with: jilbabs are compulsory for Muslim women in fiercely religious Aceh and though non-Muslims didn’t technically have to wear them, it seemed polite to make an effort to fit in. Then I flew to Medan, the biggest city in Sumatra, and took a bus up through the tidy and well-established towns of the north-east coast. In eastern Indonesia I’d become accustomed to seeing banners congratulating a district on its fourth or fifth birthday, perhaps it’s tenth. But northern Sumatra was plantation country; the Dutch had stamped their presence on this region centuries ago. As I drove past the colonial-era villas and well-maintained Chinese shop-houses of Langkat, I noticed that the district was celebrating its 262nd birthday. The border with Aceh was marked by a change in billboards; those advertising fertilizer and pesticides were displaced by a thicket of posters promoting pairings of hopefuls for the posts of bupati and vice bupati. Most showed two gentlemen wearing the elaborate gold tea-cosy hats that signify Acehnese aristocracy, the preferred headgear of local candidates. One aspirant who had been unable to rally a running-mate left a blank cut-out where his partner’s photo should be. There was a fair bit of orange, the party colour of the incumbent governor of Aceh, Irwandi Yusuf, who was running for re-election. But the dominant colours by far were the red and black of Partai Aceh, Indonesia’s first legal regional party. Partai Aceh was the political offshoot of

Gerakan Aceh Merdeka

, the Free Aceh Movement or GAM. This was hard for me to take in; the previous time I had visited Aceh, in 1991, GAM leaders were sitting in exile in Sweden, prodding along what they said was a fight to the death against the Indonesian state. Now these same men wanted to be elected officials of that state.

Free Aceh was a separatist movement begun (under a series of different names) by an Acehnese businessman called Hasan di Tiro, who had been based in the US for many years. In 1976 he returned to Indonesia and declared himself head of an independent Aceh. He appointed a full cabinet of ministers, including many of his friends and relatives. In his memoirs he describes reading Nietzsche, listening to classical music and writing patriotic plays in the jungles of Aceh for just over two years before Suharto’s army weeded him out. He ran off to exile in Sweden in 1979, and the rebellion sputtered to a halt. It was kick-started again a decade later, after Hasan di Tiro managed to organize guerrilla training in Libya for a group of young rebels-in-waiting. At the time, though, it wasn’t really clear that separatists were behind the new wave of violence.

From where I sat in the Reuters newsroom in Jakarta, the first signs of trouble were reports in the national news agency, Antara, of small raids on police and army posts in rural Aceh. I ambushed military spokesman General Nurhadi outside his office and asked him about the attacks. Were the raiders separatist rebels hoping to split from the state? ‘Rebels? Nonsense! They are common criminals!’ he declared. Though the way he referred to them as

Gerakan Pengacau Keamanan

– ‘Security Disturbing Movement’, or GPK for short – suggested they were more organized than most common criminals.

*

He had trouble explaining, just a few weeks later, why the government had rounded up a clutch of these common criminals and put them on trial for subversion and separatism. Or why our minders at the Department of Information wouldn’t let journalists visit Aceh.

In July of 1990 I waltzed up to Defence Minister Benny Moerdani at a cocktail party – I was twenty-five and didn’t know any better – and asked him with a smile if I was being denied access to Aceh because the military was killing civilians in the province. When I think about that now, it makes me queasy. Moerdani was the person who had overseen the extra-judicial killing of criminals that Suharto confessed to in his autobiography; he was not a man to be crossed lightly. But the general smiled back at me. ‘Not at all, my dear, you can go any time you like. We have nothing to hide.’ With BBC correspondent Claire Bolderson, I visited Aceh several times over the following two years, trying to make sense of a very messy situation.

At the time, it was impossible to tell who was behind the attacks. Only once, we saw a letter addressed to Indonesian newspaper editors, claiming responsibility for this wave of raids. Written entirely in lower-case, the letter was an eccentrically spelled mish-mash of anti-Javanese invective, childish threats, wounded pride and separatist rhetoric. In a one-page communication, the name of the organization was variously given as: the national liberation front acheh sumatra (that one in English), neugara islam atjeh sumatra, atjeh meurdekha sumatra and atjeh merdeka.

But in the coffee shops of Aceh, the site of endless political plotting over the centuries, none of these names was ever used. People called the troublemakers the GPK, just as the government did, and they had many theories about who they were. Most involved some combination of the following: disgruntled former soldiers who had been fired in a short-lived campaign against corruption in the military; thugs who wanted a bigger share of the marijuana trade (

saus ganja

was once a common ingredient in the cuisine of the region, and Aceh remained a centre of production for the crop); hot-blooded separatists back from training in Libya. It seemed wildly improbable to me that an organization that didn’t have a shift key on its typewriter and couldn’t spell its own name would be linked to international terror training networks; it was only years later that I found that some of the fighters were indeed graduates from Middle Eastern training camps, though all the other theories also proved to be true.

What I did find at the time was plenty of brutality on all sides. Convoys of army trucks barrelled down the main highway along Aceh’s east coast, lights flashing, horns blaring. In the back of one truck, we saw soldiers in black balaclavas waving their semi-automatics over the heads of a small posse of bedraggled captives. A helicopter whumped overhead. Every few kilometres there was a checkpoint, manned by blustering Javanese soldiers in their late teens. Who are they looking for? I asked one bus driver, himself a former soldier. He laughed. ‘Headaches. They are looking for headaches.’ The checkpoint soldiers beat people up for no reason. People whose ID cards were out of date were made to swallow the laminated plastic. ‘They’re putting revenge in a savings account,’ said the squaddie-turned-driver.

Schoolchildren told us that they would no longer take the short cut through the plantation to class in the mornings because they so often found dead bodies dumped there by soldiers. The ‘rebels’ were no less vicious. An NGO worker in a remote mountain village said she had recently seen a soldier’s corpse left on the roadside by the rebels, stripped naked ‘for the flies to feast on’, his penis hanging out of his mouth. ‘The GPK [rebels] come to your door and ask for rice,’ she said. ‘You don’t give it to them, they shoot you. You do give it to them, the army will come tomorrow and shoot you. If you’re lucky, they’ll leave the body in the village, where your family can bury it. If you’re not, it will end up in a ditch miles away where no one will dare touch it except the flies and the dogs.’ Denying people a decent Islamic funeral was one of the greatest black marks levelled at both sides.

The conflict was fuelled by a reinvention of Aceh’s complex past by rebel leader Hasan di Tiro. From his Swedish exile, he proclaimed a simple version of history, one that could only mean war.

Aceh has always been rich. For centuries it sold pepper, camphor, gold, silk and other goods to Arab traders. Passing along the coast of Sumatra in 1290, Marco Polo describes the kingdom of Ferelech (thought to be near present-day Lhokseumawe on the east coast) as a place of ‘Saracen merchants, who come with their vessels and have converted the people to the laws of Mohammad’. It is the first record of an Islamic state in South East Asia, though the Italian explorer did note that the converts didn’t extend beyond the city (in the hills beyond were cannibals who worshipped the first thing they saw when they rose in the morning). The ‘Saracens’ and those who followed have left their mark on the population; many Acehnese are tall and well built, with smooth, caramel skin, aquiline features and fiery eyes. They call their homeland the Veranda of Mecca.