Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (13 page)

As we shall see, these “indestructible swarms” have truly had their innings since Davydov’s time. We have already observed them in the insurgencies that overthrew colonial rule in so many parts of the twentieth-

century world, and in places like Vietnam, where even American superpower was humbled. We see them again now in the form of the networked, globally dispersed guerrilla/terror movement that has confounded the leading nations of the world since 9/11. If Davydov was right, the prospects for mastering the challenge posed by these swarms are not bright. Their similarity to earlier Muslim resistance to Western control is profound and deep, as will be seen in the next chapter.

DESERT MYSTIC:

ABD EL-KADER

Universal Dimensions of Islam

While this is a book about the great captains of irregular warfare, it also indirectly concerns the countries that have had deep experience with this form of conflict. By now it should be clear that France is one of these countries. We have seen in preceding chapters that French soldiers fought against Rogers, on the same side as Greene, and then once again were opposed to Mina and Davydov. In later chapters the French military will also be seen in action against Giuseppe Garibaldi in Italy and Vo Nguyen Giap in Vietnam. But immediately next is the seventeen-year struggle (1830–1847) to impose French rule upon Algeria, a land from which one of the great Muslim insurgent leaders arose. In this long war French forces, by dint of their extensive experience with irregular warfare, would once again prove formidable opponents. Their insurgent adversary would thus have to demonstrate the highest level of skill simply in order to remain in the field against them, much less to prevail—as he very nearly did.

Exactly why Charles X, the restored Bourbon monarch of France, sought to conquer Algeria remains a subject of debate. The king’s stated goal of ending piracy, the international terrorism of that age, was unconvincing even then, as Algeria had already curtailed the operations of its corsairs by 1815. There was also some talk of bringing Western morals and governance practices to a benighted people, a theme that resonates with our era’s nation-building mantra. But France could hardly be seen as a paragon of governance, given the Revolution, the Terror, Bonapartism, and the shaky Restoration. Indeed, Charles’s efforts to reimpose strong monarchical rule in France would lead to yet another revolution, just as the invasion of Algeria was getting under way. His successor, Louis-Philippe I, the last king of France, would rule with an ever-weaker hand over the next two decades. France could hardly have been seen as an appropriate ambassador for the spread of good governance. At best, an Algerian war was a temporary diversion from domestic French woes.

This leaves us to consider baser motivations. Chief among them was the financial dispute that arose when Algerian commercial grain interests sought repayment from France for shipments that had kept the French people fed during the long years of the British naval blockade against Napoleon. The Algerians’ dunning irritated the French, and the dispute grew more bitter, leading to the 1827 “flyswatter incident.” The Turkish satrap, Dey Husayn of Algiers, fed up with the French consul’s dismissive attitude toward the debt—which amounted, with interest, to more than twenty-four million gold francs at this point—apparently slapped him with his fly whisk, a terrible breach of diplomatic form that outraged the French and made them still more reluctant to pay their debt.

In the following months Husayn ratcheted up the pressure by closing down French trading posts in Algeria. The French in turn imposed a naval blockade of the country. At this point Husayn seems to have authorized piratical action against French merchant ships plying their trade in the Mediterranean, which stoked French anger, some of it now righteous. A kind of strategic logic also came into play, the belief that France’s naval position would be greatly strengthened by obtaining bases in North Africa.

Lastly, in terms of securing a “green light” from the other great powers, the post-Napoleonic Concert of Europe acquiesced in the French action. It may have appeared to many in Europe that an adventure in Algeria would be a useful diversion of resurgent French strength. Keeping Paris’s attention elsewhere, far from the hurly-burly at the center of European power politics was, it seemed, a good idea.

Thus in May 1830 Charles shipped off more than thirty thousand troops to invade Algeria. The French were confident that resistance would be weak, given the disunity of the Arab tribes and their broad resentment of the corrupt and inefficient rule of the local representative of the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople, or Stamboul.

1

At the outset all went well. Under the command of General Auguste-Louis de Bourmont, French forces captured Algiers in a few weeks. The Dey’s treasury had been seized with enough gold to pay for the invasion’s cost to date. The general was well pleased, so much so that he sent a triumphal message to his monarch: “The whole kingdom of Algeria will probably surrender within fifteen days, without our having to fire another shot.”

2

Mission accomplished.

A week after this predicted end to the fighting, a strong French column was ambushed about thirty miles from Algiers and nearly wiped out. To this continuing, and growing, resistance was added confusion about whether the mission would be sustained once Charles fell from power in July. The situation soon righted itself, however, as the French Chamber of Deputies acclaimed Louis-Philippe I king—or, as he was to be known, the citizen king. The new monarch had fought heroically in the early battles of the Revolution, leaving France only after the king and queen were executed. He was not the man to walk away from this small war.

But the war soon got bigger, for the Algerians were not as disunited as the French assumed. Partly this was so because the very act of invasion had given the Arab and Berber tribesmen common cause—the goal of expelling the infidel occupier. Another catalyst was to come in the form of a young, charismatic leader, one Abd el-Kader (Servant of the Almighty). The son of a respected Sufi mystic,

3

Muhi al-Din, he was only twenty-five at the time. But he had already made his pilgrimage to Mecca, and during the journey he had met Shamil, who would soon lead Muslim resistance to Russian expansion in the Caucasus. Abd el-Kader was equally well schooled in theology and the military and diplomatic arts, as his father had foreseen that Algeria would one day have need of a great leader who combined the spirit and the scimitar.

But even Muhi al-Din, whom the great social observer Alexis de Tocqueville described as “saintly,”

4

did not think his son’s time had come. Instead he called for the Algerian tribes to ally themselves with the sultan of neighboring, independent Morocco, who he thought was the appropriate authority for leading this defensive holy war, or jihad, to protect the people. Muhi al-Din’s faith was misplaced, however, as it seems that the sultan may have felt better about having French rather than Turkish rule in Algeria, and the Moroccan troops he sent under his son’s command were soon fighting against the very tribesmen who had sought his assistance.

At this point Muhi al-Din reconsidered his son’s readiness for command and, out of necessity—he himself was too old and frail to take charge—used his moral authority to gain acceptance from the tribes for Abd el-Kader’s accession to leadership of the resistance against the French. It helped greatly that his son’s natural modesty and courtesy appealed strongly to the independent-minded tribal leaders. It also helped that, despite his small stature—being just over five feet tall—Abd el-Kader was a masterful horseman and swordsman, with a magnetic gaze and a quiet but eloquent manner of speech.

In his very first proclamation, made in Mascara on November 22, 1832, Abd el-Kader conjured a vision of broader unity among the people than they had ever imagined. As he explained the purpose of the war of liberation,

it may be the means for uniting the Muslim community and of preventing dissensions among them and of affording security to all the inhabitants of the land, of putting an end to lawlessness, and of driving back the enemy who has invaded our country in order to subjugate us.

5

With such words he lit a flame in Algeria that would never be fully extinguished, despite his ultimate defeat and the century of French occupation that would follow. The insurgents who would finally win Algeria’s independence in 1962 were inspired and guided by the remarkable campaigns of this great jihadi general.

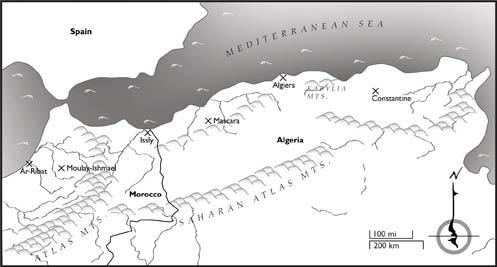

Abd el-Kader’s Area of Operations

*

At the outset of the war for Algeria, the French were unprepared for the level of unity the tribes were able to achieve, and were completely befuddled by the tactics they employed. Basically Abd el-Kader relied on the tribes’ abilities to conduct classic Bedouin raids, or

RAZZIAS

. His forces had greater mobility—in terms of speed of movement and (thanks to camels) an ability to move great distances off road. And, due to the support of the increasingly oppressed and outraged Algerian public, they had excellent intelligence about French dispositions. For their part, the French relied upon mass and firepower, especially artillery, to cow their opponents. But the tribes fought in small bands, picking and choosing when they would strike, whether at balky French columns on the march or against isolated outposts. Initially, the insurgents had a field day against French forces, whose own frustrations led them to commit atrocities that only further alienated the populace.

Compounding these problems, General Bourmont also made the mistake of thinking his principal problem was with the Turks in power, so he proceeded to “de-Turkify” the Algerian civil administration. This soon left him with no one who understood how to make the society work—much as “de-Ba’athification” would cause chaos in Iraq some 170 years later.

General Bourmont was sacked soon after Charles X fell and was replaced with a somewhat more competent but far more brutal successor, Pierre Boyer. A veteran of some of the toughest fighting against the insurgents in Spain, Boyer inflicted great punishment on the innocent because he could not come to grips with the tribal raiders. Pierre the Cruel, as he came to be known, was also Pierre the Conventional, remaining slow, clumsy, and road-bound in his efforts to confront the guerrillas. The insurgency thrived, and by 1833 Abd el-Kader and those allied with him controlled about two-thirds of Algeria, all but a few strips along the country’s northern coast.

The French now brought in a new commander, General Louis-Alexis Desmichels. He was a cavalryman of repute, having fought heroically in some of the major battles of the Napoleonic Wars. From the start he understood the need for swift, light forces that could catch the insurgents unawares and pursue them with some hope of making captures. His forces began to engage the enemy more often and, on occasion, came off the better. Abd el-Kader had his first serious opponent, and the two men sparred for some time.

During this period the jihadi leader’s father passed away. Suspicion remains to this day that Muhi al-Din was assassinated—and the French general’s home government in Paris, riven with dissent, deprived him of resources. Both leaders were thus concerned about their ability to maintain the fight, Abd el-Kader worrying mostly about preserving unity, Desmichels driven to distraction by deficiencies in men and arms. This situation led them, by a kind of tacit consent, to begin peace negotiations using Jewish Algerians—who understood both Arab and French cultures and languages—as intermediaries.

The result of these negotiations was the Desmichels Treaty, signed February 26, 1834, which recognized and accepted the French presence in Algeria but at the same time gave de facto consent to Abd el-Kader’s rule over the tribes and control of much of the territory and commerce of Algeria. But this peace, so carefully arrived at between Desmichels and Abd el-Kader, was to prove short lived. As it turned out, the French translation of the treaty gave rather greater colonial control to the occupiers while the Arab version sharply limited the Europeans’ encroachments on Algerian sovereignty.

6