Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (35 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Thus a host of British elite forces formed up, including the Special Boat Service, the Special Air Service, and the Long Range Desert Group. More than crafting such capabilities in his own military, however, Churchill—and the few others who were open to such ideas—also wanted to promote insurgencies among the occupied peoples of Europe. Some among Americans also supported this notion upon their country’s entry into the war at the close of 1941. Soon small Allied “Jedburgh” teams—named after the castle where they trained—were parachuting into occupied territory to help organize resistance and conduct sabotage.

During the years of Nazi control, armed insurgents sprang up in virtually every occupied country. Europe truly was “set ablaze,” per Churchill’s order. But the strategic results of this irregular campaign were mixed. The Germans responded ruthlessly to such insurgent attacks, killing large numbers in reprisal for any losses they suffered. They were also skillful at infiltrating resistance units, rolling up insurgent networks with alarming regularity. The commandos, coming ashore from small boats, and the Jedburghs, who usually parachuted in, suffered enormous casualties. German occupation, for the most part, didn’t end until massive armies invaded and drove them out in bitter fighting.

Overall the sense of most leading historians is that the Special Operations Executive and the various resistance movements, even the large number of Russian partisans operating behind German lines in the East, had for the most part little strategic effect. Of the most dramatic rising, that of the Poles in August 1944, the military historian John Keegan concluded that the Germans “found the means to fight—and eventually defeat—the insurgents without drawing on their front-line strength.”

2

Such was the case in virtually all the other antiguerrilla campaigns conducted by the armed forces of the Third Reich.

But there was one insurgency whose results proved an important exception to the often lackluster performance of other commandos and resistance fighters: the struggle against the Nazis in Yugoslavia led by Josip Broz, the man who came to be known to the world as “Tito.” In nearly four years of continuous fighting after the German invasion in the spring of 1941—one of Hitler’s drives that quickly and easily defeated the government forces arrayed against his

WEHRMACHT

—Tito would demonstrate his mastery of many aspects of irregular warfare and roll back the occupation.

He succeeded in doing so, for the most part, with little material assistance from either the Russians or the Western Allies. For some time the Red Army was far too busy fighting off the Germans; later, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin saw little of value in allowing a strong indigenous movement to arise in an area where he hoped to hold postwar sway. And the British, for their part, spent the first years of the resistance in Yugoslavia supporting the more favored general of the monarchy-in-exile, one Draja Mihailovich, whose Serbian “Chetniks” spent much of their time trying to weaken or destroy Tito.

Yugoslavia was a young nation cobbled together in the wake of World War I. The Germans were well aware of the ethnic and social divisions that roiled just below its surface, and exploited them with considerable skill. They also maintained large numbers of troops in the country, adding to their forces as the European war turned against them, out of fear of an Allied landing in the Balkans. Thus as the war dragged on their relatively small occupation force increased to twenty-five divisions (eight of them Bulgarian, some Italian forces too), well over a quarter million troops. The occupiers also enjoyed local air superiority for the most part, which allowed them to bomb resistance strongholds and from time to time to mount airborne operations.

At the outset, in the summer of 1941, Tito surveyed a bleak scene, and conditions throughout most of his remarkable campaign remained daunting. He had to fight for years with little outside support, and struggled against both the highly skilled German military and the main resistance forces of Mihailovich favored by his own country’s legitimate government. But Tito had advantages too. Yugoslavia’s mountainous terrain made it difficult for the occupiers to operate easily with large forces, which allowed Tito to “packetize” his own units and disperse them throughout the country. This dispersal was not unlike Lockwood’s choice of sending lone submarines out to a wide range of distant patrol areas, and was also similar in placing a premium on having fine local commanders who were capable of operating with minimal instruction.

Indeed, it was said that the skills of Tito’s best lieutenants—Djilas, Kardelj, Popovic, and Ribar—were so consummate that all Tito had to do in a major strategy session was point to one of them, saying “

TI

” (you), then to a point on the map, saying “

TO

” (that). This may or may not have been the origin of his

NOM DE GUERRE

,

“

Tito.” More likely “Tito” was just a code name he used during his early days as a socialist/Communist agitator. It was a Croat name occasionally used at the time, rendered in English as Titus.

For all the skills of those around him, Tito was himself an accomplished soldier. Born in 1892 in a Croatian village near Zagreb, then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he was drafted into its army the year before World War I broke out. He took to soldiering naturally, very soon rising to sergeant. He was particularly adept at fencing and won a service-wide competition on the eve of war. But during the Balkan crisis that led to the wider conflict, and even after the fighting started, Tito began acting on his growing socialist sentiments, spreading antiwar propaganda among the troops. Briefly imprisoned, he was released and sent off to fight the Russians.

He distinguished himself in battle and was soon promoted to sergeant major, the youngest in the Austro-Hungarian Army. But even fine soldiers suffer misfortunes, and in 1915 Tito was wounded and captured by the Russians. After treatment in hospital, he was sent to a prisoner-of-war labor camp in Siberia and was later released by the Bolsheviks during the revolution. He joined the Reds in the Russian civil war, and made his way back to Yugoslavia at the end of the major fighting in 1920, with a teenaged wife, Polka, in tow. He found steady work as a machinist during these years but also served as a Communist organizer. His party prospered under the constitutional monarchy, becoming the third-largest faction in the Yugoslav legislature, holding nearly sixty seats.

The rise of the Communists was viewed with great concern by the government, and in 1928 a crackdown ensued in which Tito found himself once more in prison. Instead of the few months of incarceration he suffered at the hands of the Habsburgs, or his year-plus as a POW in Russia, this time he was imprisoned for five years. Upon his release he moved to Vienna, himself, as his wife had left him while he was in prison. Next he went to the Soviet Union for a year, becoming a member of the NKVD, the organization from which the KGB would emerge. He had apparently gained Stalin’s favor during his stay in the USSR. For during this time of Soviet purges of all those even suspected of disloyalty, the secretary general of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia fell victim to “official murder” while in Moscow in 1937. Tito, on his return to his homeland, took his place. Although the Communists were still not a legal party, Tito, now “Comrade Walter,” continued to lead and organize it, building secret cells and nodes in a network that would prove highly useful during the years of resistance to the Nazis. Indeed, after King Peter II fled during the invasion in 1941, it was the Communists who mounted the opening attacks on the Germans.

But this first uprising, characterized by mass action in several places, was easily put down—much as the French dealt with the popular insurrection against their rule in Spain in 1808, the only major difference being that the Germans had considerable help from local collaborators, including Tito’s own Croats. Thus, like so many of the other masters of irregular warfare, Tito suffered a very serious reverse at the outset of a crucial campaign. He would learn from it, crafting a new concept of operations that would ultimately defeat smart, tough, and more numerous foes. And he and his colleagues would do it largely on their own.

*

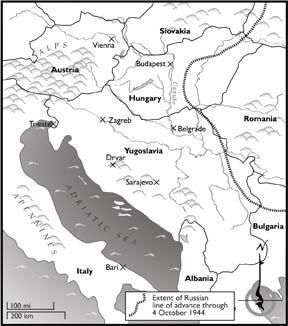

By the fall of 1941 Tito had about fifteen thousand fighters under him, roughly the manpower of a reinforced infantry division, but much of his force was without weapons. Still, he commanded roughly triple the number of troops that Mihailovich had. Most were deployed in northern Yugoslavia, which made them particularly susceptible to an offensive by a corps (three divisions) of crack German troops who drove them out of Serbia in less than a week that November. Tito and the men who escaped the German net made their way south to Bosnia, but there was little rest to be had. A new offensive mounted by Italian troops and Croat collaborators soon drove them down to Montenegro. Here the rough terrain made it hard for enemy forces to get at them, but it was even harder for the insurgents to strike back from their remote mountain fastnesses.

The Partisan War in Yugoslavia

This was the low point of Tito’s campaign. The Germans, Italians, and their Yugoslav collaborators had proved militarily adept at fighting in rough terrain and were absolutely ruthless in their dealings with civilians who they thought might be aiding the insurgents. Atrocities swiftly mounted, turning Yugoslavia into what Churchill sadly called “the scene of fearful events.”

3

For his part, Mihailovich came to a “live and let live” accommodation with the occupiers while he served as the official leader of the resistance authorized by the government-in-exile and was receiving British aid. Indeed, his Chetniks went even farther down the path of treachery, often providing information to the Nazis about Tito’s forces.

It was during this crisis that Tito devised what turned out to be the war-winning idea of mounting a wide-ranging offensive with small combat formations. In the darkest days of the fight he ordered a march north, keeping some fighters in the south and dispersing his forces widely among his trusted subordinates. All of these “columns” recruited vigorously while on the march. Soon the occupiers found that, far from having successfully pacified Yugoslavia, they now had to deal with insurgent activities erupting in several different places at the same time—a “strategic swarm,” if you will. Tito’s bold stroke resembled the daring offensive move made by Nathanael Greene at one of the lowest points during the American Revolution, which reenergized the guerrilla campaign in the south.

The German reply to the renewed insurgent threat was to send ever more troops, amounting to well over a hundred thousand in 1942, and more than double that number of German and other Axis-allied troops under German command by the end of 1943.

4

These antiguerrilla forces conducted large-scale counteroffensives that led to the killing or capture of thousands of Tito’s fighters and came close to catching him on more than one occasion.

But such sledgehammer blows could only deal with parts of the insurgency at any one time. And when counterinsurgent forces moved to deal with a threat emanating from another area, the seemingly hacked-off limb of the resistance in the province they had just come from grew back, often stronger than before. As Walter Laqueur has described the central reason for the turnaround, “Tito had realized that the strength of the partisan movement lay in its dispersal.”

5

Coming to grips with the fact that they were dealing with a hydra-headed insurgency, the Germans began trying different methods for coping with the multitude of small enemy units striking in many places. First they attempted to rediscover Kitchener’s methods from the Boer War, in particular his mix of blockhouses and rapid reaction forces. In the German case in Yugoslavia, these consisted of a network of

STUETZPUNKTE

(“strong points”) and a ranger-like force called the

JAGDKOMMANDO

(“hunter command”). The arrays of mini-forts were strategically placed at important junctions—roughly six miles apart—and the commandos were situated in places where they could rapidly come to the aid of a number of threatened posts.

6

But these were mostly defense-oriented changes. The Germans knew they needed to be able to use their many small units they had created on the offensive as well, and here again they borrowed from Kitchener. Where “sweeps” had dominated the “de Wet hunts” forty years earlier, the Germans now used the same tactic of deploying hunter units to push the insurgents into a waiting line of troops, calling it a “partridge drive.” Other tactics included the simpler “battue shooting,” in which all the small units on the edge of the encirclement would simultaneously drive inward.