Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits (30 page)

Read Insurgents, Raiders, and Bandits Online

Authors: John Arquilla

Lawrence did not live to explore fully the potential of airpower. He fell victim to a motorcycle crash in May 1935 when he had to swerve too sharply to avoid hitting two boys on bicycles. He was forty-six. Churchill walked behind his casket at the funeral, later commenting to the

TIMES

of London that Lawrence was “one of the greatest beings of our time.”

20

Lawrence’s untimely death kept him from being a part of the airpower-driven future of military affairs; but another great master of irregular warfare, the subject of the next chapter, was soon to take up this cause.

LONG RANGER:

ORDE WINGATE

© Bettmann/Corbis

By dint of his deeds, but especially by the eloquent words he later used to describe and draw lessons from the Arab Revolt—notably his brilliant summary of the state of guerrilla doctrine in the fourteenth edition of the

ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA

—T. E. Lawrence greatly refreshed what Walter Laqueur called an “arid” era in irregular warfare.

1

In the years after World War I, insurgency seemed to revive, while modern terrorism appeared seriously for the first time. The Russian civil war, fought mostly between 1918 and 1920, was replete with both hit-and-run raiding tactics and cold-blooded acts of terror, including regicide. Similarly bitter irregular violence was the norm in Ireland, where insurgents shifted from the failed approach of the 1916 mass rising to embrace more guerrilla-like action in pursuit of independence. In Mexico, Pancho Villa effectively began his insurgency against repressive rule—and even ran rings around American forces chasing him—but he ended badly after reverting to conventional tactics.

Some of the most illuminating examples of insurgency and terror tactics during this period came from the Muslim world, sparked both by admiration for the success of Lawrence’s methods in the Arab Revolt and resentment of the European powers’ continuing colonial meddling throughout so much of the Maghreb and the Middle East. In northwest Africa, for example, the guerrilla campaign of Abd el Krim in Morocco, a land then divided between Spain and France, even featured a small insurgent air force, perhaps an homage to Lawrence’s enthusiastic views about the value of airpower to irregulars. But after years of reverses, the two colonial powers finally realized the need to act together, and Abd el Krim’s revolt was put down decisively.

Sudan was another troubled place, plagued as it was by

HABASHI

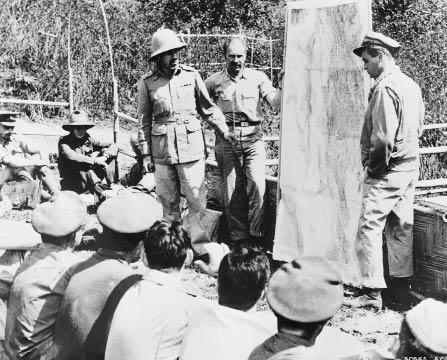

slave raiders who preyed upon remote villages, a practice that had gone on for centuries and still occurs there. The British, who had controlled the country after Kitchener’s defeat of the Dervishes at Omdurman in 1898, at first tried the usual limited range of conventional methods, including garrisoned outposts, patrols, and the development of native forces. None worked well until a young army lieutenant by the name of Orde Wingate was posted there in 1928. (Shown on the previous page—Wingate at a briefing, wearing his trademark pith helmet.)

Twenty-five at the time, Wingate had become interested in Middle Eastern affairs and studied Arabic at the urging of his father’s cousin, Sir Reginald Wingate, who had worked with Lawrence, one of the young officer’s heroes at the time.

2

Wingate was even distantly related to Lawrence on his mother’s side, and the families occasionally socialized. Upon his arrival in Sudan, Orde Wingate began to think deeply about the slave raiding problem and soon began experimenting with methods for dealing with it that were radically different from what had been tried before. He raised some eyebrows, but the young lieutenant was given permission for these ventures, and he seized the opportunity.

Two things distinguished Orde Wingate’s approach to dealing with the

HABASHIS

: his determination to take the offensive against them and his willingness to lead small teams of Sudanese on long treks to set ambushes for them. The results of this seemingly simple shift were to prove remarkable. Wingate’s basic pattern of action began when warning came from a border village that a raiding party was en route. He would set out immediately on a course aimed at intercepting the raiders in the remotest places rather than at watering holes, villages, or other likely sites. Many decades before global positioning systems, Wingate had an uncanny ability to reckon his exact location in the wilderness. And his ambushes were meticulously and ruthlessly carried out. His concept of operations soon forged a kind of deterrence of the raiders, and their activities waned.

Wingate spent five years in Sudan, developing his field craft and honing his larger ideas about what he would eventually call “long range penetration.” His notions about the power of even small units when used to launch deep strikes against one’s adversaries, while related to the actions of Denis Davydov, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and even T. E. Lawrence, went much further, for he demonstrated that these methods could also be employed against slippery irregular forces, not only conventional formations.

After leaving Sudan in 1933, Wingate had a tour of duty in Britain, during which time he married. In 1936 he was sent overseas again. This time Wingate, whose language skills included Hebrew and Arabic, found himself posted to Palestine as an intelligence officer. It was a difficult time there, as Jewish settlement had been rising in recent years, igniting tensions with the Arabs who increasingly felt betrayed by broken British promises of self-rule. The numbers of Jews arriving partly reflected Zionist enthusiasm and hope for an independent homeland; but immigration was also being fed by a growing stream of refugees coming out of Germany after Hitler’s takeover in 1933. It was not long before violence broke out between Jews and Arabs.

As in Sudan, Wingate, now a captain, came into a situation where the problem was raiders, but this time they were killing to intimidate settlers, not attacking in search of slaves. The Arabs were determined not to become a minority in what they saw as their own land, one that had been promised to them. Also as in Sudan, the British response had been a primarily defensive one. Their forces patrolled Palestine’s borders apparently endlessly, and though they allowed Jewish settlers to defend their settlements, they permitted no more than that.

Little progress was made against the Arab insurgents, even though gifted soldiers like Bernard Montgomery—at this point a lower-ranking general but destined to become Britain’s premier field commander during World War II—were sent to grapple with the nettlesome problem. Another troubling factor in play at the time was that the basic sentiments among the British were overwhelmingly pro-Arab, and anti-Semitism ran high throughout the ranks. The desire to pursue operations against the Arab insurgents was low.

From the moment he came to Palestine, Wingate proved to be an exception to prevailing British practices and attitudes. He quickly saw that his ideas about offensive long-range operations could be applied as effectively in Palestine as they had been in Sudan. He would visit with Jewish settlers, talking up the possibilities of forming strike forces to cripple the Arab terrorists. For Wingate, “terrorism” was the right way to describe the Arab actions, given the raids on settlements in which innocent women and children were being killed. But he was also motivated by his own deep Christian belief, nurtured by his parents and the tenets of the Plymouth Brethren faith to which he adhered devoutly, that the Jews were destined to return to Israel. He intended to act in accord with God’s will.

Technically Wingate was posted as the intelligence officer in Nazareth. But he was seldom there, preferring instead to make the rounds of settlements, trying to persuade leaders of the Jewish self-defense force, the

HAGANAH

, that their basic strategy was far too passive. It took some time, but Wingate finally convinced the Jews of his sincerity. Yet as their faith in him deepened, his own superiors grew more hostile to the obviously pro-Zionist activities of this junior intelligence officer. Thus Wingate found himself in a kind of race against time in which he strove to make headway with the Jews before he was removed from the field.

Wingate greatly aided his cause, even as he alienated his peers, by violating the chain of command and sending a memorandum directly to the general officer in charge, Archibald Wavell, which called for intensive study of the “incidence, type and numerical strength of the marauders, particularly whence they came and what frontier points they used.”

3

Wavell was impressed by this message and called Wingate in for a meeting on the subject. He quickly concluded that his subordinate was on to something and authorized him to pursue his investigation. Wavell and others thought Wingate would do this by examining incident files. Instead he took to the field.

What followed was a series of meetings with Jewish settlers, and even with the secretive leadership of the

HAGANAH

. Wingate assured them that with a small number of elite troops he could seize the initiative and hold it against the Arabs. He used his favorite example, that of the biblical Gideon, who chose just three hundred from among thousands to conduct his remarkable, stealthy military operations. With a similar-sized force, Wingate argued, he could achieve similarly great results. The

HAGANAH

, persuaded that they could trust the man they now spoke of in code as

HAYEDID

, the “friend,” accepted Wingate’s proposal.

After a period of training in his offensive concepts as well as in his more general “Soldiers’ Ten Commandments”—which in some ways echoed Robert Rogers’s rules for rangers—Wingate was ready to begin his counterinsurgency operations with these newly formed Special Night Squads (SNS). They were comprised mostly of settlers, with a leavening of British noncommissioned officers and other ranks. As in Sudan, Wingate relied heavily upon an information system to provide early warning, but to this he added a proactive tactic of firing on Arab villages his force might come upon in the night, to gauge the reaction. If there was heavy return fire, he knew there was something to investigate.

The campaign that unfolded turned the tables on the Arab insurgents. No longer could they count on having the initiative to select their targets and strike first. The Jews showed up everywhere the raiders intended to attack. Increasingly the SNS also found its way to the villages from which insurgent actions were staged. Even when the Arabs tried to create their own surveillance system, watching for trucks that carried the SNS, Wingate foiled them by training his men to slip off the backs of the trucks one by one at dusk, undetected, rallying at a prearranged point from which they proceeded on foot. This was easy to do because the SNS was an extremely light force, armed only with rifles, grenades, and long poles, which were used to hold torches at a small distance from their exact locations in the bush, allowing teams to signal each other without becoming easy sniper targets.

4

Wingate’s force was lacking in numbers—fewer than a hundred

HAGANAH

fighters served with him, formed into nine teams and filled out with a handful of Jewish police.

5

But they made up for their small size and lack of firepower with total relentlessness. In battle they took to the attack, no matter the size of the opposing force, their British commander always in the thick of the fight. He was there too when prisoners were being questioned, on at least one occasion ordering the execution of a captive so as to encourage the others to speak.

6

His greatest success came at a place called Dabburiyah, near the Sea of Galilee, where a major insurgent group that had been attacking both Jewish settlers and the British oil pipeline was destroyed, very nearly to the last man. Wingate was wounded in three places during the action, but kept on fighting and leading, afterward earning both the Distinguished Service Order and promotion to major.

For all this success—by 1939 insurgent attacks dropped off sharply—Wingate’s superiors also became aware of and hotly opposed to what they considered his extreme methods. A further cause of opposition to Wingate, aside from general British antipathy to the unorthodoxy and brutality of such practices and disdain for the Jews, was that many of his colleagues simply disliked him as an individual. He was arrogant and brusque far beyond his rank. He was also deliberately slovenly, often going about unshaven in a field-stained uniform and wearing a battered pith helmet. It was a kind of “anti-brand,” quite different from T. E. Lawrence’s skillfully crafted image in flowing white robes. But this “look” showed everybody, from those in headquarters to the

KIBBUTZNIKS

, that he was a fighter.