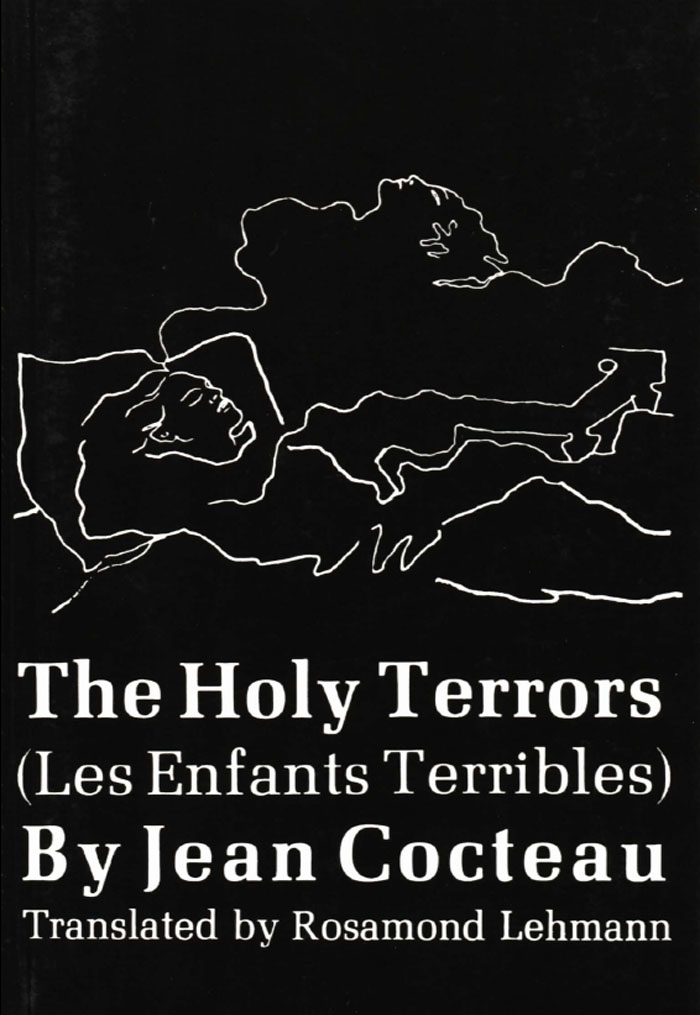

The Holy Terrors (Les Enfants Terribles)

Read The Holy Terrors (Les Enfants Terribles) Online

Authors: Jean Cocteau

HOLY TERRORS

BY

JEAN COCTEAU

with illustrations by the author

translated by

Rosamond Lehmann

BOOK

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

As if manipulating an imaginary train

The new game in the dining room

The loved faces resemble each other

ONE

T

HAT PORTION of old

Paris known as the Cité Monthiers is bounded on the one side by the rue de

Clichy, on the other by the rue d’Amsterdam. Should you choose to approach it from

the rue de Clichy, you would come to a pair of wrought iron gates: but if you were to

come by way of the rue d’Amsterdam, you would reach another entrance, open day and

night, and giving access, first to a block of tenements, and then to the courtyard

proper, an oblong court containing a row of small private dwellings secretively disposed

beneath the flat towering walls of the main structure. Clearly these little houses must

be the abode of artists. The windows are blind, covered with photographers’

drapes, but it is comparatively easy to guess what they conceal: rooms chock-a-block

with weapons and lengths of brocade, with canvases depicting basketfuls of cats, or the

families of Bolivian diplomats. Here dwells the Master, illustrious, unacknowledged,

well-nigh prostrated by the weight of his public honors and commissions, with all this

dumb provincial stronghold to seal him from disturbance.

Twice a day, however, at half-past ten in the morning and four o’clock in the

afternoon, the silence is shattered by a sound of tumult. The doors of the little

Lycée Condorcet, opposite number 72b rue d’Amsterdam, open, and a horde of

schoolboys emerges to occupy the Cité and set up their headquarters. Thus it has

reassumed a sort of medieval character—something in the nature of a Court of Love,

a Wonder Fair, an Athletes’ Stadium, a Stamp Exchange; also a gangsters’

tribune

cum

place of public execution; also a breeding-ground for hazing

schemes—hazing to be hatched out finally in class, after long incubation, before

the incredulous eyes of the authorities. Terrors they are, these lads, and no

mistake—the terrors of the Fifth. A year from now, having become the Fourth, they

will have shaken the dust of the rue d’Amsterdam from their shoes and swaggered

into the rue Caumartin with their four books bound with a strap and a square of felt in

lieu of a satchel.

But now they are in the Fifth, where the tenebrous instincts of childhood still

predominate: animal, vegetable instincts, almost indefinable because they operate in

regions below conscious memory, and vanish without trace, like some of

childhood’s griefs; and also because children stop talking when grown-ups draw

nigh. They stop talking; they take on the aspect of beings of a different order of

creation—conjuring themselves at will an instantaneous coat of bristles or

assuming the bland passivity of some form of plant life. Their rites are obscure,

inexorably secret; calling, we know, for infinite cunning, for ordeal by fear and

torture; requiring victims, summary executions, human sacrifices. The particular

mysteries are impenetrable; the faithful speak a cryptic tongue; even if we were to

chance to overhear unseen, we would be none the wiser. Their trade is all in postage

stamps and marbles. Their tribute goes to swell the pockets of the demi-gods and

leaders; the mutter of conspiracy is shrouded in a deafening din. Should one of that

tribe of prosperous, hermetically preserved artists happen to pull the cord that works

those drapes across his window, I doubt if the spectacle thereby revealed to him would

strike him as copy for any of his favorite subjects: nothing he could use to make a

pretty picture with a title such as “Little Black Sweeps at Play in a White

World”; or “Hot Cockles”; or “Merry Wee Rascals.”

There was snow that evening. The snow had gone on falling steadily since yesterday,

thereby radically altering the original design. The Cité had withdrawn in time;

the snow seemed no longer to be impartially distributed over the whole, warm, living

earth, but to be dropping, piling only upon this one isolated spot.

The hard, muddy ground had already been smashed, churned up, crushed, stamped into slides

by children on their way to school. The soiled snow made ruts along the gutter. But the

snow had also become the snow on porches, steps, and house-fronts: featherweight

packages, mats, cornices, odds and ends of wadding, ethereal yet crystallized, seemed,

instead of blurring the outlines of the stone, to quicken it, to imbue it with a kind of

presage.

Gleaming with the soft effulgence of a luminous dial, the snow’s incandescence,

self-engendered, reached inward to probe the very soul of luxury and draw it forth

through stone till it was visible; it was that fabric magically upholstering the

Cité, shrinking it and transforming it into a phantom drawing-room.

Seen from below, the prospect had less to recommend it. The street lamps shed a feeble

light upon what looked like a deserted battlefield. Frost-flayed, the ground had split,

was broken up into fissured blocks, like crazy pavement. In front of every street drain,

a stack of grimy snow stood ominous, a potential ambush; the gas-jets flickered in a

villainous northeaster; and dark holes and corners already hid their dead.

Viewed from this angle, the illusion produced was altogether different. Houses were no

longer boxes in some legendary theater but houses deliberately blacked out, barricaded

by their occupants to hinder the enemy’s advance.

In fact the entire Cité had lost its civic status, its character of open mart,

fairground, and place of execution. The blizzard had commandeered it totally, imposed

upon it a specifically military rôle, a particular strategic function. By ten

minutes past four, the operation had developed to the point where none could venture

from the porch without incurring risk. Beneath that porch the reservists were assembled,

their numbers swollen by the newcomers who continued to arrive singly or two by two.

“Seen Dargelos?”

“Yes … no … I don’t know.”

This reply came from one of two youths engaged in bringing in one of the first

casualties. He had a handkerchief tied round his knee and was hopping along between them

and clinging to their shoulders.

The question had come from a boy with a pale face and melancholy eyes—the eyes of a

cripple. He walked with a limp, and his long cloak hung oddly, as if concealing some

deformity, some strange protuberance or hump. But nearing a corner piled with school

haversacks, he suddenly flung his cloak back, exposing the nature of his disability: not

a growth, but a heavy satchel eccentrically balanced on one hip. He dropped it, ceased

to be a cripple; the eyes, however, did not alter.

He advanced towards the battle.

To the right, where the footpath joined the arcade, a prisoner was being subjected to

interrogation. By the spasmodic flaring of a gas lamp he could be seen to be a small boy

with his back against the wall, hemmed in by his captors, a group of four. One of these,

a senior boy, was squatting between his legs and twisting his ears, to the accompaniment

of a series of hideous facial contortions. By way of crowning horror, the monstrous

ever-changing mask confronting the prisoner’s was dumb. Weeping, he sought to

close his eyes, to avert his head. But every time he struggled, his torturer seized a

fistful of gray snow and scrubbed his ears with it.

Circumnavigating the group, threading a path through shot and shell, the pale boy went on

his way.

He was looking for Dargelos, whom he loved.

It was the worse for him because he was condemned to love without forewarning of

love’s nature. His sickness was unremitting and incurable—a state of

desire, chaste, innocent of aim or name.

Dargelos was the Lycée’s star performer. He throve on popular support and

equally on opposition. At the mere sight of those disheveled locks of his, those scarred

and gory knees, that coat with its enthralling pockets, the pale boy lost his head.

The battle gives him courage. He will run; he will seek out Dargelos, fight shoulder to

shoulder by his side, defend him, show him what mettle he is made of.

The snow went flying, bursting against cloaks, spattering the walls with stars. Here and

there, some fragmentary image stood out in stereoscopic detail between one blindness and

the next; a gaping mouth in a red face; a hand pointing—at whom? in what

direction? … It is at him, none other, that the hand is pointing; he staggers;

his pale lips open to frame a shout. He had discerned a figure, one of the god’s

acolytes, standing on some front door steps. It is he, this acolyte, who compasses his

doom. “Darg….” His cry is cut off short; the snowball comes

crashing on his mouth, his jaws are stuffed with snow, his tongue is paralyzed. He has

just time to see the laughter and within the laughter, surrounded by his staff, a form,

the form of Dargelos, crowned with blazing cheeks and tumbled hair, rearing itself up

with a tremendous gesture.

A blow strikes him full on the breast. A heavy blow. A marble-fisted blow. A

marble-hearted blow. His mind fades out, surmising Dargelos upon a kind of dais,

supernaturally lit; the arm of Dargelos nerveless, dropping down.

He lay prostrate on the ground. A stream of blood flowed from his mouth, besmearing chin

and cheek and soaking into the snow. Whistles rang out. Next moment the Cité was

deserted. Only a few remained beside the body, not to succor it but to observe the blood

with avid curiosity. Of these, one or two soon made off, not liking the look of things,

shrugging, wagging their heads portentously; others made a dive for their satchels and

skidded away. The group containing Dargelos remained upon the steps, immobilized. At

length authority appeared in the shape of the proctor and the college porter and headed

by a boy, Gérard, whom Paul had hailed upon entering the battle, and who had run

to fetch them after having witnessed the disaster. Between them the two men took up the

body; the proctor turned to scan the shadows.

“Is that you, Dargelos?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“Follow me.”

The procession started.

Great are the prerogatives of beauty, subduing even those not consciously aware of it.

Dargelos was a favorite with the masters. The proctor felt the whole baffling business

to be excessively annoying.