Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder (30 page)

Read Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder Online

Authors: Gitta Sereny

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #Military, #World War II, #World, #Jewish, #Holocaust, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #Ideologies & Doctrines, #Fascism, #International & World Politics, #European

“Then of course there were terrible ones; Kurt Franz, Küttner, Miete, Mentz; animals, sadists. But there were such people amongst the Jews too: the

Judenrath

in Warsaw, the Jewish Gestapo; and then in Treblinka, the Kapos, the squealers, some of them again better than others, but on the whole I was as scared of them as of the Germans.

“My parents and my twenty-year-old sister were sent to Treblinka a week before me. I had got married six weeks earlier. Not a love match – a sort of ‘arrangement’; she had money – our families arranged it. Her mother, sisters and brothers – she no longer had a father – were also shipped to Treblinka a week before us. But she and I had been sent to the

SS HQ

to work – we were both young and strong. The day we were ordered to the

Umschlagplatz

[the square from which the transports departed], the

HQ

officers said they didn’t want to lose their workers. There was a lot of discussion and finally it was decided that all bachelors could stay but married couples had to go. An announcement was made that ‘anyone who wants a divorce could have one, right away’. Well, it was a choice between life and death. [Earlier he had said that they had no idea where the trains were going; a little later, “Perhaps we didn’t know for certain, but we had a good idea what it was”; this was in July 1942, at the very beginning of the camp.] I saw men who had been married for thirty-four years ask for a divorce then and there. My wife – well, I told you, it wasn’t love between us but – she said, ‘I am going to be soap anyway, so ask for a divorce, save yourself.’ But I thought to myself, ‘I have no family, nobody left. She has nobody. We’ll stay together.’ So both of us went.

“As soon as we got to Treblinka I was selected to work. They called me

Langer

[long one] because I was so big and tall. I said to the

SS

who picked me out, that she was my wife and could she work too. And he – I can’t remember who it was, Miete or Küttner – he said, ‘Don’t worry, she is going to work in the laundry in Camp II.’ But of course, it wasn’t true; they killed her right away. I never saw her again.

“They put me first in the Red Command – we had to superintend the undressing in the undressing barracks. We had to call out, ‘

Ganz nackt, Schuhe zusammenbinden, Geld und Dokumente mitnehmen.

’ [He called it out for me, to show me how: ‘Strip, tie your shoes together, take along money and documents.’] That’s how they fooled people. They thought they were going to bathe and be disinfected and that they were being allowed to keep their valuables and documents with them for their own protection. It reassured them. Some German Jews-you know, they were more German than the Germans – were very authoritarian, very much the

Herren

[the gentlemen – or masters]. ‘Keep an eye on my shoes will you, till I come back,’ they’d say condescendingly, you know, to us of the Red Command. Of course, ten minutes later they were dead.

“Later I was appointed to the disinfection room, probably one of the worst places to be in; it was between the hairdressers who chopped off the women’s hair, and the ‘tube’ which led up to the gas chambers. We would have to disinfect the hair, you see, right away, before it was packed up to ship – they used it in Germany to make mattresses.

“Stangl?” he said. “I never saw him kill or hurt anyone. But why should he have? He didn’t have to. He was no sadist like some of the others, and he was the Kommandant. Why should he dirty his own hands? It’s like me now in my job; if I have to fire somebody,

I

don’t do it – why should I? I tell somebody else to tell the person he is fired. Why should I do the dirty job myself? Stangl never beat anybody either,” he said. “Why should he? Oh, he was there when it was done of course … well …” – he retracted, as he was to do in almost every instance when he mentioned Stangl’s being present at or taking part in anything – “He

must

have been there; they were all there. And he was the Kommandant. I tell you exactly the way it was;

I

was there for a year, and I know. Anyone tells you differently, anyone tells you Stangl beat or killed anyone, or anyone tells you Stangl

talked

to them – they are lying. He didn’t talk to any Jews – why should he?

“Did I have friends? Yes, of course I had friends. All right, yes, I had friends. But how could one have friends there? I never did any harm to anyone. I kept myself to myself – it was better. But they liked me – the others. On my birthday, I remember, I was going to have a bit of a party and I managed to buy some ham off a Ukrainian and the Germans found it. They lined us up and asked whose it was … nobody budged … but then one of my pals said it was his. So I said no, it was mine. They marched us to the

Lazarett

*

and told us to undress. Only shortly before, we had taken a friend of mine who was very ill there – to be killed; nobody went there for any other reason. But when we were carrying him, on the stretcher, he asked me and I told him that no, we weren’t taking him to the

Lazarett

– he was going to the

Revier

– the sick room. Anyway, when we were pushed in there ourselves, Hansbert, this friend, was still burning in the pit. And then they began to shoot our group. One, then the next, the third, the fourth–I was fifth and last, and by that time I was lying on top of the others [he must have fallen forward] waiting to be shot. I turned around, looked up and said, ‘Hurry up, why don’t you. Shoot, for God’s sake.’ And then, whoever it was … I think it was Miete who had come … said for me to get up and get dressed. Well, they must have liked me – otherwise they would have killed me too.” (It was probably Miete who had originally picked him out for work, in which case he was possibly now seeing him to some extent as his protégé.)

*

The

Lazarett

was nothing but a shell of a small building – about twelve metres by twelve, with a Red Cross painted on the front. There was no roof. Immediately inside the door was a weather-shelter for the SS guard, and a small table and bench. Just beyond was an earthen wall running almost the length of the building with a pit on its other side. Victims were helped to undress, then had to sit on that wall, were shot in the neck and dropped into the permanently burning pit.

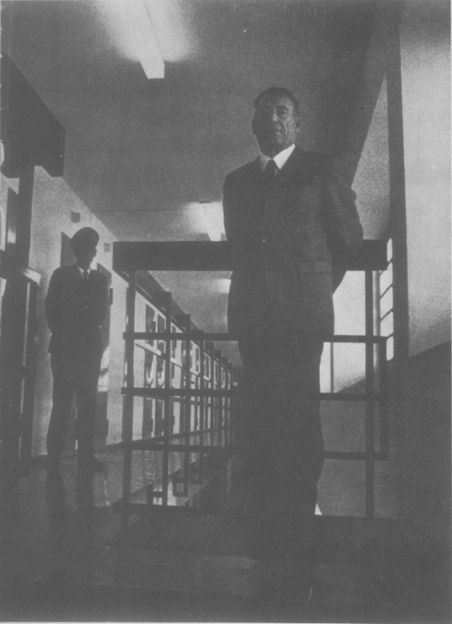

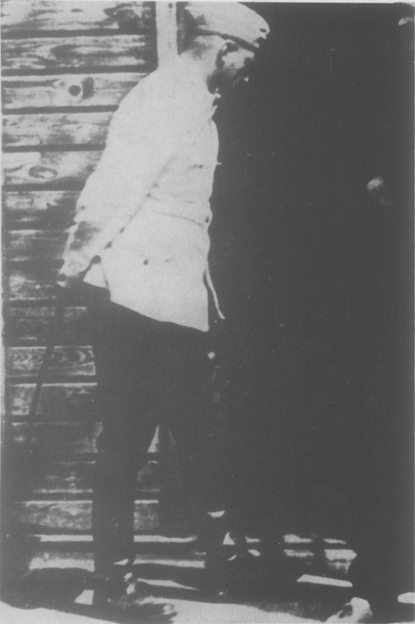

Franz Stangl in the Remand Prison at Düsseldorf, having prepared himself for the photographer

Left

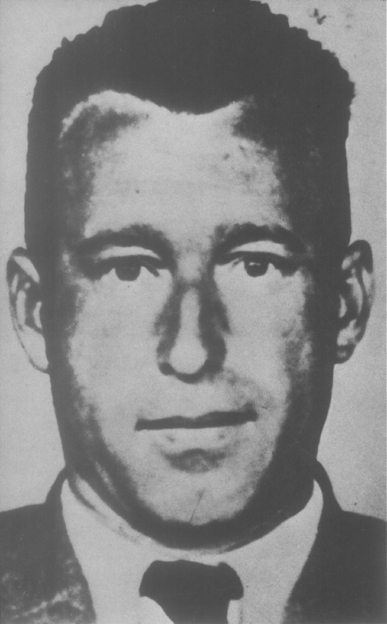

The photograph of Franz Stangl issued by the Jewish Documentation Centre at Vienna at the time of his arrest in Brazil

right

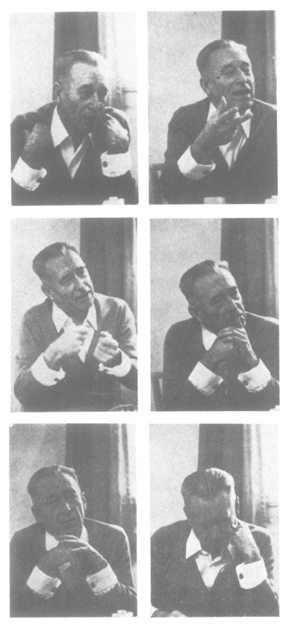

Franz Stangl in conversation with the author

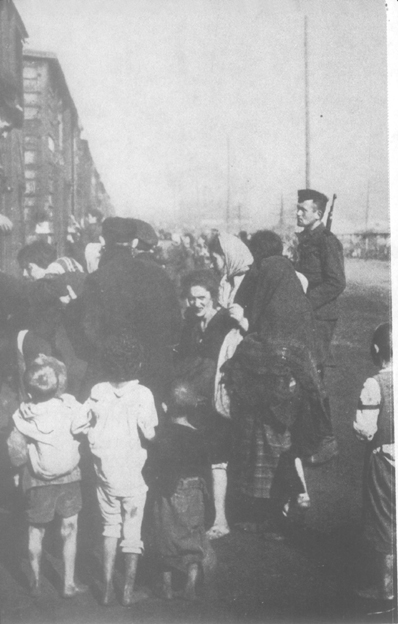

Three of the photographs of a transport bound for Treblinka, taken secretly at Siedlce Station, on August 22, 1942, by an Austrian soldier, Hubert Pfoch

Franz Stangl at Treblinka, talking to his adjutant Kurt Franz. He is wearing the white jacket often referred to at his trial