Into the Storm (15 page)

Authors: Dennis N.t. Perkins

âListen to That

T

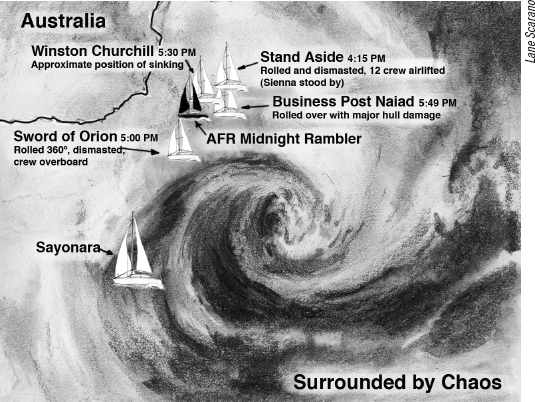

he airwaves were filled with sounds of anguish and desperation. Aboard

AFR Midnight Rambler

, the crew listened to the frightening Maydays and man overboard alerts. They heard helicopters coming to the rescue of stricken boats, searching for people lost in the water.

These were men they knew. Friends they had shared time with and sailed with, not just competitors. Some, like Jim Lawler, they knew personally. It was sobering, and everyone on board the

Rambler

knew the danger. A wave that had knocked down and dismasted another boat could have just as easily crushed them.

Ed, Arthur, and Bob were steering magnificently, and the members of the crew were supporting each other with exceptional teamwork. But it was impossible to ignore the tragedies unfolding around them.

VC Off-shore Stand Aside

had been hit to the north, less than 20 miles away.

Winston Churchill

, close behind them, had sunk.

Sword of Orion

had met its fate about 20 miles to the south. And

Business Post Naiad

had rolled about 10 miles to the east. It was excruciatingly apparent that

AFR Midnight Rambler

was in the bull's-eye of a deadly target. (See illustration on p. 120.)

Bob Thomas was steering the boat as straight as he could. With Mix blocking the waves, he hung on, ducked as low as he could, and let the water break over him. Three times the waves ripped Bob from the helm and slammed him down into the cockpit. Each time he would lunge toward the tiller, push it over hard, and focus on getting over the next one.

Bob was a disciplined master mariner, trained in lifeboat drills and sea safety. He had faith in his boat, and he believed the little

Rambler

would survive. But with the mayhem surrounding them, he needed to prepare the crew for the worst.

Abandoning ship is always a last resort, but sometimes it has to be done. The crew of

Winston Churchill

had no choice but to take to their life rafts. If the

Rambler

reached that point, Bob wanted to make sure that they would leave the boat in the right way. They would not throw the life raft over the side of the boat, inflate it, and expect everything to work out. It would be a planned, methodical operation.

With Ed at the helm, Bob went down below to brief the off-watch crew on everything they would need to do if the boat went down. He calmly explained the process and assigned tasks to each member of the crew. Some were to get the life raft on deck. Others were to grab the

ditch bag

, which they dubbed the

panic pack

. The panic pack held flares, the EPIRB, and other essentials for survival. They discussed other things, including water bottles and flashlights. The irony was that no oneâespecially Bobâexhibited any display of panic when talking about the panic pack.

“If we have to go to a life raft, it's got to be a very controlled procedure so that we all get into the life raft,” Bob said. He was emphatic in saying that the process of leaving the

Midnight Rambler

had to be precise. Otherwise, two or three men could jump into the raft and be blown away, leaving the rest of them alone on a sinking boat.

After briefing the crew down below, Bob climbed on deck and told Ed about what had just happened. Ed understood and agreed: They needed to be ready for anything. Then, while Arthur steered and Mix spotted waves, Bob repeated the instructions he had given below.

It was an intense moment. As bad as conditions were, they knew things were going to get worse. The fact that Bob was now talking matter-of-factly about the life raft meant that they were headed into further trouble.

The winds were blowing around 65 knots, and waves continued to crash over the boat. The wind, screaming through the rigging, made conversation almost impossible. But Bob talked calmly, speaking right next to their ears.

“A lot of boats are in trouble,” he explained, “and conditions ahead are as serious as those behind.” Bob repeated his instructions about the panic pack, the spare EPIRB, the flares, the location of the lifeboats, and how they should be deployed. Finally, he reiterated the cardinal rule for abandoning ship: “Always step up into a life raft, never down.” The meaning was clear:

AFR Midnight Rambler

needed to be unquestionably sinking before they would even consider getting into a life raft.

Though Bob went through the whole process very deliberately, it hit Mix squarely just how serious conditions were. If bigger boats ahead and behind them were sinking, what chance did a 35-foot boat have? They could only beat this storm with a combination of teamwork, skill, and luck. They had no control over luck, but they were skilled sailors. And they continued to work together with extraordinary cohesion.

At the helm, Arthur thought that the faces of the waves were about the length of a football field. They were big, steep stretches of water, and the only advantage the small

Rambler

had was its maneuverability. Arthur would move across the face of the wave, and, if he didn't like what he saw to his left, he would go right.

In the troughs, the breeze would drop and the

Rambler

was protected by the face of the waves. Arthur would get a brief relief, but it wasn't much. He was still surrounded by deafening noise and spew. It was just that the boat was a little bit more in control. But soon the

Rambler

would be sucked into the next wave.

Arthur would feel the boat being pulled ahead, and the

Rambler

would rise up the face of the wave. As they reached the top, the boat would be hit by the full intensity of the wind, and the

Rambler

would tilt dramatically. With rain and spew hitting him in the face, Arthur would contemplate his next move. He had to find a path through the next wave.

Steering a boat in these conditions required total concentration. It was exhausting. Ed's ability at the helm was unsurpassedâthere was no question about thatâand he would bear the heaviest burden. But

AFR Midnight Rambler

had two others who could drive and give him relief from the arduous task of steering. And they also had a system so that fresh people would be on deck every hour.

In these conditions, there were going to be mistakes, but minimizing errors and recovering quickly were critical. The Ramblers' ability to share the helm meant that there were far fewer blunders than if one person had been steering without relief. And their reflexes were far better when they needed to react.

Even with the watch system, the Ramblers were at their limits. The crew had been fighting the weather since eleven o'clock that morning. By 7 p.m. the storm's ferocity was still building. Arthur looked at his watch and thought,

It's still getting worse. Eight hours is a long time when you know the next wave may kill you

.

As he tried to comprehend what they'd gotten themselves into, another disaster metaphor popped into his head. This wasn't like a car accident, where things happen and it's over. In a car accident, if you live and you're okay, you can say, “That was close.” This seemed like it was never going to be over. It was ever present and it was getting worse. It was a hard, frightening feeling.

About 8 p.m., Bob relieved Arthur at the helm. Arthur and Ed were in bunks below, trying to rest. The

Rambler

was a racing boat. The bunks were tight and uncomfortable. Ed kept thinking,

It's like lying in a coffin

. It wasn't a good way to think about it, he realized, but

coffin

was the word that kept coming to mind. The brothers were about 6 inches apart, their heads almost touching. They weren't sleeping; it was impossible. They just lay in their bunks, exhausted.

Suddenly, Arthur spoke. “Listen to that,” he said. Ed's first reaction was that something had broken.

He's heard something come apart

, Ed thought. Gear failure in these conditions could mean fatalities. Ed's mind raced:

Oh, no, here we go. It's about to happen

. Then he said aloud, “No, I can't hear it. What are you talking about? Listen to what?”

“Ed,” said Arthur. Arthur was very emotional, choked up, close to tears. “You can hear Bob,” he said. “You can hear Bob in the cockpit. You can hear him talk.”

Ed listened, and he could hear Bob talking to Mix and Jonno on deck saying, “The wind's dropping.” The screaming kettle had stopped. Minutes before, you could be right next to someone and you couldn't hear him. Now you could hear people in the cockpit giving orders. You could hear the world again.

In the space of a half hour, the wind had gone from 80 knots to 40. The wind was still gale force, but Arthur was elated. A gale was survivable. He was going to see his family again. He was going to do whatever he needed to make it home.

No matter what happens

, Arthur thought,

I'm going to fight harder to get through whatever it throws at us. We're going to keep going

.

Ed became emotional as well, tearing up with the realization of what his brother had just said to him. Arthur was telling Ed that they had survived something ghastly. They had made it through the worst of the horrible storm.

The two brothers were lying there together, feelings of relief flooding through them. The connection was unspoken. Arthur had communicated everything with one choked-up sentence:

Listen to that

. When Ed realized what Arthur was saying, he had responded with one word: “Yes.” Nothing more needed to be said. They had gotten through the storm together, and they knew they were going back to the land of the living. Together.

At that instant, there was a dramatic shift in the race. But it was not over, and they had not reached safety yet. Everything below deck was soaked. There was water everywhere, and their electronics were a disaster. The main GPS had failed, the portable GPS wasn't working, the radio was coming in and out, and they had nothing to navigate with.

Their wind instruments had been blown off the mast, and all they had left was a compass fixed to the cockpit on deck. Ed thought it was like Captain Cook when he came to Australia. They were in the middle of the Bass Strait with only a compass, sailing by the seat of their pants.

There were no lighthouses to get a bearing from, and they couldn't use the sextant. The sextant, though antiquated, was a reliable navigational instrumentâbut only if they could see the stars. And there was no chance of that.

The Ramblers were not out of danger, but Ed had faith in Bob. Together, they had done eight Hobarts, and Ed had come to know Bob's sixth sense as a navigator. Ed trusted Bob's ability to dead reckonâto estimate their position with nothing but a chart, a compass, and a pencil.

For the next fourteen hours Bob plotted their course south, estimating their direction, speed, and leewayâthe sideways movement caused by the force of the wind and waves. The chart was sopping wet from floating in the seawater and was pretty much unreadable. It was scary not knowing exactly where they were. All they knew was that they were somewhere in the Bass Strait. But they knew where they were going, and, with Bob's navigational skills and a compass, that might be enough.

They had enough for primitive navigation, but without a radio they had no way of knowing what was happening around them. They didn't know the fate of the sailors who had been on the damaged boats. And they didn't know about the other boats that were hit after

Business Post Naiad

. The plight of another boat would compound the fears of their loved ones.

At the time of the 2 p.m. sked,

Midnight Special

had been within a mile of

AFR Midnight Rambler. Midnight Special

was doing exceptionally wellâbut with the wind increasing and boats with experienced sailors turning around, they decided to run for shelter. Their plan was to steer north to Gabo Island, only 38 miles away.

Turning around may have felt like the safest course, but

Midnight Special

was hit by large waves again and again. The boat was knocked down repeatedly. Crew members were injured, but the boat seemed to be holding together.