Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes (13 page)

Read Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes Online

Authors: Kamal Al-Solaylee

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Middle East, #General

The wedding turned into an explosion of bad taste, according to my still-snobbish father. My siblings and I thought it was funny, and we joked about it for months afterwards. Instead of a banquet hall in one of the major hotels in downtown Cairo—as in Faiza’s first wedding—the groom booked a seedy nightclub in the dodgy entertainment area called the Pyramids Road. The area became famous for fleecing Gulf-area tourists with overpriced admission tickets and menus. The entertainment consisted of seven—count them, seven—unknown belly dancers and a couple of no-name singers. There was no shortage of food, and a huge orange-coloured wedding cake that my father wouldn’t eat. In another example of the gap between my parents, my mother asked the waiters to put the leftovers in boxes to take home—to the mortification of my father, who wanted no reminder of that evening.

Looking back at this wedding in 1981, I now realize that it was the last time my parents and all of their children were under the same roof. Mohamed could no longer allow his family to live in a society that restricted his freedom and theirs to seek work and make a living. After a couple of exploratory visits to Sana’a—visits that he never enjoyed—he decided to move the family headquarters there gradually over the next year or two.

Helmi volunteered himself as a canary. He was the first to leave Cairo behind, in the fall of 1982, and start a new life in Sana’a. He had some friends to fall back on, and my uncle Hussein, my father’s younger brother, had already established himself somewhat. I can’t say that I was all that sad to see Helmi go. He was becoming erratic in his observance—sometimes hardline and sometimes permissive when it suited his needs. He had one set of religious rules for himself and another for his sisters. His friends had too much influence on his thinking and often made me feel self-conscious about my perceived femininity or, to put it in the proper Egyptian context, lack of manly aggression. Well before “man up” became a catchphrase in American politics, I heard its Arabic equivalent from his friends. My mother had a harder time with his departure and cried for days on end. Not only was he to go to Yemen, but he had to start his life there by fulfilling the obligatory one-year military service in President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s armed forces. My sisters breathed a sigh of relief, at least temporarily, for they knew they’d follow in his footsteps soon enough.

STILL, FOR ABOUT A YEAR

or so the mood in the house became relaxed and we got to enjoy the old Cairo that we loved. Two years after the assassination of Sadat, and two into Mubarak’s regime, Cairo was settling into a kind of stability. Yes, incidents of terrorism took place—attacks on government buildings or Christian churches—and the streets got more dangerous late at night because of increased crime and poverty, but we felt safer than we had in Beirut and knew Cairo was a lot more modern and tolerant than Sana’a.

By the time I turned eighteen I was a high-school graduate. Unlike most of my friends and even my own siblings I had no firm plans or any real ambition to go to university. All I wanted was to get more comfortable in my skin. After floundering for a year, I applied to Ain Shams University, a left-leaning alternative institution in Cairo, to study business and economics. I didn’t have the confidence to enrol in the English program after going over the first-year reading list. To me, English wasn’t about literature but a gateway to life as a gay man. I even read up on the gay liberation movement in New York and San Francisco, two cities I made a pilgrimage to in 1991 just to see all the places—Christopher Street, the Castro—I’d read about as a teen in Cairo. I obtained my information about gay life in the West from second-hand weekly news and entertainment magazines like

Newsweek

and, of all titles,

People.

Once a week I went to the market in downtown Cairo, the Azbakia, where they were sold. Many American expatriates sold their old magazines, which were then lapped up by Western-media-hungry people like me. To save money I’d walk all the way there and back—an hour in each direction—and spend all I had on magazines. You got the best deals and the widest selection on Mondays, as the expatriates would clean up their apartments on Sunday and get rid of magazines they didn’t want. My sisters loved looking at the ads more than the content. We couldn’t believe how available and attractive everything seemed in America. We’d see ads for food and clothes and assume that was how everybody in the West must have lived. In Cairo, the idea of a supermarket was novel. A handful of them popped up in more upscale neighbourhoods in the late 1970s and early ‘80s. Up to that point, all the food we consumed came from the open markets or local convenience stores that sold the staples: sugar, milk, cheese and so on. The idea of buying bread (and not buying it fresh daily) anywhere but at a bakery would have been laughable to my mother.

As we flipped through those magazines, my sisters and I wanted to sample the same types of food. We thought of the newly opened and relatively expensive McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken as treats for special occasions—as did most of our circle of friends. In the hierarchy of foreign foods, however, pizza occupied the top slot. It was like nothing we ever ate, and whenever we visited friends or other families where they served it, we considered it a sign of sophistication. Most Egyptian families adapted the toppings to suit local palates, so they didn’t use much pepperoni or oregano and instead opted for minced meat, hot pepper and tuna.

Raja’a and I, however, wanted to try the original pizza as we saw it in the American ads. So she and I went to a supermarket on Mousadak Street, not very far from our new family home, and searched in the frozen-food section until we found a pizza that looked most like the ones in the magazines. We first had to make sure that the pepperoni was made of beef and not ham, and when we established that, we rushed home to allow it to defrost. The instructions were in English, so I did my best to translate to Raja’a and my mother, who regarded with suspicion the idea of a frozen meal that came inside a cardboard box. To the best of our ability we followed all the instructions—including taking off the cellophane wrapping—and stuck it in the oven for forty to fifty minutes. (We didn’t realize that was for cooking from frozen.) When my mother began to suspect the pizza was getting burnt, she took it out of the oven, removed the scorched crusts, cut it into slices and gathered whoever was at home to try it. She wouldn’t accept it as the main meal and categorized it for now as a snack. We all took one bite and stopped. It tasted awful. I insisted that it was meant to taste that way, but my mother would have none of it. She collected all the slices, put them in a garbage bag and threw it down the chute. It was the taste of oregano that must have thrown us off. From then on, whenever we craved pizza, we had to go out or follow my mother’s traditional recipe. To me it wasn’t pizza; just everyday food on dough.

Aside from magazines, radio became a lifeline. I got hooked on the BBC World Service for its music programming and Voice of America, which broadcast both in English and Arabic. Immersing myself in Western culture and art made me less self-conscious about my sexuality. The connections were being made in my mind: English offered a way out; Arabic a step backward. I remember talking to myself in English as I walked home from the movies or from magazine-shopping sprees. I refused to watch Arabic movies or TV shows. As my family gathered in the living room for their daily dose of Egyptian soap operas, I retreated to the room I shared with my two brothers and listened to the radio or watched anything in English on the second TV channel. (There were only two in Egypt, and we didn’t get a VCR until 1985.) I took great pride in not knowing what my mother and siblings were talking about when they discussed TV shows. And as for Arabic music, that was completely banished from my record collection. I erased all those tapes of my favourite Egyptian singer, Shadia, and used them to record American and British top-twenty hits from the radio. Thursdays were for the British singles chart countdown on the BBC; Fridays for the

Billboard

US one.

Three decades later, as a man in my late forties, I find it inexplicable that I turned my back on Arabic music, because I think that music is so lovely now. It comforts me and fulfils an emotional need. Maybe I’m just trying to make up for the years I rejected it. I would love to attend a concert by Shadia or Nagat El-Saghira now, both of whom retired and distanced themselves from their musical careers once they’d converted to a strict reading of Islam.

BETWEEN

1983

AND

1984, my mother, four of my sisters and my brother Khairy joined Helmi in Sana’a. It was the first time I’d lived apart from my mother, and it didn’t take me long to realize that I was indeed a mama’s boy. Even though she didn’t speak English and was not remotely interested in my choice of music and entertainment, she never stood in the way of my enjoying them and never made a value judgement about the corrupting influence of the language or the music. Every now and then, when Khairy came home from the mosque and found me watching Western music videos on TV, he’d make a comment about how it was all an American conspiracy to get Arab youth to forget about Islam and the Palestinian cause. I just wanted to watch Wham! and, my favourite English band, Spandau Ballet.

A former English high-school teacher suggested that if I liked that culture so much, I should learn more about its history and literature, and after floundering for a couple of years, I got my act together and switched programs from business to English. I didn’t necessarily think of it as a subject for a university degree but as a way to polish my English writing and as a stepping stone to finish off my education in England. Faiza was still living there and in 1984 invited me to visit.

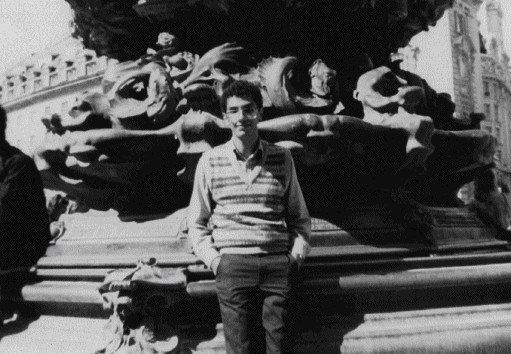

A picture of me taken by a family friend during my first visit to London in 1984. That trip changed my life and helped me come out as a gay man.

I don’t think I slept for weeks prior to my flight to Heathrow. I’d dreamed of such trip for many years. There were two small obstacles to overcome, however: getting a UK visa and my father’s approval (and some money). My first application for an entry visa was turned down because I hadn’t bought a return ticket. I was crushed, but once I re-submitted the application with the ticket (which my brother-in-law paid for in Liverpool), I was given a single-entry visa. Getting Mohamed’s approval and financial support was far more complicated. He’d made it clear that he worried about my losing my way completely if I was exposed to more Western culture. He thought I’d be brainwashed and find life back in Cairo or Yemen too restrictive. He relented only after Faiza promised she’d look after me and not let me out alone.

Finally, I thought, I was getting to go to London, not realizing that Liverpool was three hours away by train—and, more disappointingly, not knowing that Faiza and my aunt lived only in England by name. When I arrived in Liverpool, I discovered they still listened to Arabic music, watched Arabic films, cooked Arabic food and socialized only with other Arabs. Visiting my aunt’s house in the multiethnic neighbourhood of Granby felt like I had never left the Middle East—except the streets were full of Asian and black people as well, all of whom kept to themselves. Even with part of my family living in England, I had to get away from them. I wanted to see the real England, so I hit record and book stores for hours during the day and was glued to the TV at night. I bought (and hid) my first copy of a gay magazine and daydreamed about a point in my life where I didn’t have to read it secretly late at night. But it would be four years, and another summer visit to England, before that would happen.

When I returned to Cairo after that first visit, and as he’d predicted, my father and I started to argue much more. I’d tasted freedom and wanted more of it. As he travelled back and forth between Sana’a and Cairo to check in on us, he got stricter and stricter. He disapproved of me going out with friends late at night and always questioned their background. If you grew up in the Middle East, you got used to controlling parents, but Mohamed’s interference suggested one of two things: his fear that I’d be experimenting sexually in the age of AIDS or, in a more Freudian twist, resentment towards me for becoming a better speaker and writer of English, a language in which he was as good as a native speaker. With my mother and most of my sisters in Yemen now, there was no buffer between the two of us.

He was right about the sexual experimentation. The visit to England gave me a confidence boost and I found the courage to call the Liverpool gay helpline and ask for information on finding other gay men in Cairo. Much to my surprise, the helpful operator said that the international gay guide

Spartacus

listed some bars in downtown Cairo as meeting places. “Are you sure?” I asked in disbelief. It was hard for me to imagine the possibility of meeting other people publically who felt the same way that I did, given how isolated my early years as a gay teen had been. “Well, the Tavern at the Cairo Nile Hilton comes up in various guides,” he replied. I knew the hotel but had no idea where that tavern was, or what to do when I got there.