Invisible Romans (31 page)

Authors: Robert C. Knapp

While elsewhere we find freedmen related to the cult of the Vestal Virgins:

Decimus Licinius Astragalus, freedman of Decimus, priest of the Vestal Virgins [dedicated this]. (

CIL

6.2150, Rome)

And to Ceres:

Publius Valerius Alexa, freedman of Publius, lived piously 70 years, a priest of Ceres; he lies here. (

ILTun

1063, Carthage)

Helvia Quarta, freedwoman, priestess of Ceres and Venus while alive set up this monument for herself. (

CIL

9.3089, Sulmona, Italy)

Thus freedmen were active in many cults. Of the approximately 250 Latin inscriptions indicating vows to gods I examined, over half, leaving aside clearly local divinities, are to gods of Roman religion: Jupiter in his many guises, Hercules, Mercury, Silvanus, Juno, Diana, Apollo, and Fortuna. Isis is the only ‘foreign’ religion represented, although other evidence makes it clear that another ‘foreign’ cult, that of the Phrygian Great Mother (

Magna Mater),

was also much used by freedmen, some of whom are attested as priests. This spread of traditional and newer

gods is typical of the record of devotion for the population in general. Once again, freedmen do not stand out from their free counterparts in the religious aspect of their social and cultural lives.

Nor do they in death. There is a cemetery filled with the graves of ordinary Romans at Isola Sacra between Rome and Ostia. In this cemetery the graves of freedmen and freeborn Romans are indistinguishable and are intermixed. There is neither ‘freedman art’ nor ‘freedman habit’ nor a ‘freedman section’ which would separate freedman’s tombs from others. As in other aspects of religion, honoring the dead was done in conformity with general standards and habits of the population. Freedmen single themselves out on grave monuments in being especially proud of their families and their freedom, but otherwise they acted just like those they had associated with while living.

Conclusion

A freedman lived with the constant incubus of a previous servile existence hovering over him. Or so we are told: The general view is that they lived under a stigmatic cloud because of their formerly servile status, and that this stigma stayed with them for life, no matter how successful. To the elite, fixated on a ‘free’ life as the only one worth living – i.e. a life ideally, if not really, free from subjection to another – the mere fact of servile origin seemed an ineradicable mark of Cain, one that doomed the bearer to a life of angst and insecurity, if not self-loathing. But the evidence does not indicate that this was, in fact, the case at all. Freedmen seemingly without blush and often with evident pride declare themselves ‘ex-slaves’ on their tombstones. While the elite might emphasize the servile origins, the freedman rather would find pride in his success as a good slave that had earned him his freedom. He had, in fact, in most cases been promoted (i.e. freed) because he was good at what his master wanted done. His previous servile condition was no fault of his, and his progression out of it a sure sign of his qualities as a human being, for he had made the most of the situation. His servile life had been his home; he normally retained good feelings for his former slave community after ‘promotion’ and once free moved easily between the two worlds, a liminal figure but not a conflicted one. Likewise, as presumably his freedom owed some if not all to a good relationship with his owner, he

could also navigate in the world of the masters, knowing when to be obsequious, when to offer advice, when to hold back, and when/how to push, whether in relations with elites or subelites, or merely with powerful freeborn foremen or other freedmen. Selected for a variety of survival and success skills, the typical freedman was multifaceted, socially savvy, and economically prepared. He was a dynamic player in the world of ordinary Romans.

6

A LIVING AT ARMS: SOLDIERS

LEGIONS MASSED TO CRUSH THE SLAVE REVOLT

of Spartacus; a fiery charge against shrieking barbarians: images of the Roman soldier are inextricably linked to the visuals of novels, film, and television. But aside from the brief moments of battle discipline, carnage, bravery, and death, what was it like to live the life of a Roman legionary? The sources, however broadly tapped, do not allow the story of the common soldier to be told at any single time during the first three centuries

AD

. However, it is possible to construct a composite picture based on material from this entire period. Massed legions, screaming barbarian hordes, bravery in battle all existed, but I will lay out the rest of the legionary’s existence in all its limitations, promise, banality, and excitement.

The legionary soldier, like other invisibles, is virtually never noted individually by the main classical sources. He appears in a mass – ‘the army’ or ‘a legion’, or some other grouping; only in exceptional and frequently semi-fictionalized situations does a soldier appear as an individual in elite writers. For these authors, the army below the command level is except in very rare situations an undifferentiated mass playing a role in the elite drama that they called history. When the elite deigned to think about common soldiers, they liked to spotlight heroic efforts, but in the end saw mostly a dangerous body, ignorant, low born, and motivated by base instincts. Looked at from the social, economic, and cultural level of the common soldier, however, his life, although it could

be hard and even at times deadly, was in many ways privileged with a stability and benefits that few other ordinary men could hope to find. This becomes clear as I look at the soldier on his own terms.

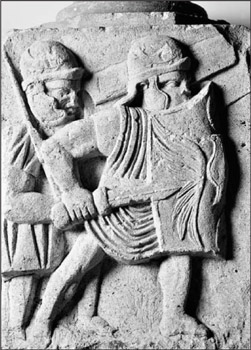

16. The army at war. Here two soldiers advance, one with the short sword (

gladius)

at ready, the other with his spear (

pilum).

Recruitment

The actual number of new recruits each year was fairly small. Thinking about the legions scattered over the empire, it is easy to forget that the term of service was long, and loss by war minimal; around 7500–10,000 or so new soldiers each year would have sufficed to keep the legions up to strength. All had to be freeborn Roman citizens; freedmen were recruited to only a few specific units, and slaves were completely ineligible during the empire – indeed, as Artemidorus states, for a slave to dream that he is a soldier means that he will be freed, because only free men could be in the legions (

Dreams

1.5). But the number of necessary recruits is not large assuming a citizen general population of around

9 million. Legions were not kept at their full ‘paper’ strength of 6000 men, but this was for financial reasons, not because there is any evidence that it was difficult finding the necessary number of recruits. The evidence for forcible recruitment, conscription, during the empire is scattered and slight. As the

Digest

16.4.10 notes, ‘Mostly the number of soldiers is supplied by volunteers.’

Almost all were between seventeen and twenty-four years of age; twenty was probably the usual age at enlistment. Elite sources liked to imagine that they all were down-and-outers. As Queen Elizabeth referred to her impressed soldiers as ‘thieves who ought to hang,’ so Tacitus talks about the needy and homeless that represent the dregs of society entering the army (

Annals

4.4). To the elite, the rough world of the ordinary and the poor could only be painted in disdainful strokes. In fact, most if not all these were young men who had grown up with their families, had learned a trade, even if this was only farming, and had now determined to set out on a new life. As the normal cultural habit was for women to marry young, in their teens, and men to marry old, in their late twenties, few recruits had started a family of their own.

Simplicitas

(simple-mindedness) and

imperitia

(ignorance) were desired qualities. Clearly, idiots were not sought out – but a person with few ideas of his own could better be molded in the appropriate ways. There were exceptions, of course. Even at the level of the common soldier, some literacy might be desired in a subgroup of recruits since these men would more easily rise to the positions of clerks in the legion (Vegetius 2.19).

Both ancients and moderns have chosen to emphasize the arduous-ness of service. But a picture of hard life is misleading if taken at face value by moderns. Once any thought of comparison between the living conditions of the Romano-Grecian world and the Western world since 1800 is put out of mind, it is clear that a soldier had a good life by ancient standards. Even if the peasant recruit went from his hard farm life to a hard soldier’s life, he labored in much better, more promising conditions than he ever could have experienced had he stayed on the farm, because in major ways the soldier’s life ameliorated the harshest aspects of that life.

In light of this, it is not surprising that recruits were not wanting. As one document from Egypt puts it, ‘If Aion wants to be a soldier, he

only need come, since everyone is becoming a soldier’ (

BGU

7.1680). Although some parents might object, most would agree with these Jewish parents who in a Talmudic story seem eager to have their son enlist:

A man came to conscript someone’s son. His father said: look at my son, what a fellow, what a hero, how tall he is. His mother too said: look at our son, how tall he is. The other answered: in your eyes he is a hero and he is tall. I do not know. Let us see whether he is tall. They measured and he proved to be small and was rejected. (

Aggadat Genesis

40.4/Isaac)

The general assumption is that parents wanting a son in the army were unusual. But there is no reason to suppose that these parents’ attitude is weird or rare – indeed, the source misses the opportunity to inform us of this, if true. On the contrary. This random mention clearly shows that service was something that could be and was sought after by parents for their children. Both parent and child realized that prospects in civilian life were overall extremely bleak, and that the army was a bright possibility in the midst of that bleakness.

So many a young man was easily attracted by the possibility of military service. Of course, such a choice would not be for everyone. Leaving the family farm or business could have its disadvantages as the known was traded for the unknown, the stability and support of a family for a new life in a different environment. The family might object. In a letter from Egypt a wife scolds her husband for encouraging a son to become a soldier:

Concerning Sarapas my son, he has not stayed with me at all, but went off to the camp to join the army. You did not do well counseling him to join the army. For when I said to him not to join, he said to me, ‘My father said to me to join the army.’ (

BGU

4.1097/Bagnall & Cribiore)

Not only was there the factor of emotional loss of a son; there was also the practical difficulty of the loss of manpower in the home in the short term, and the loss in the long term of support in old age by a grown

son. There could be (although not necessarily would be, especially later in the empire) travel distant from home. There certainly would be separation from the physical support of family, and even from news of any immediacy, given the slowness of correspondence. Letters from Egypt show that soldiers posted to distant locales continued to maintain those family ties. Presumably separation from home and kin was often not easy at the beginning, or even throughout the years of service. Apion, an Egyptian enlisting and posted to the fleet at Misenum, in Italy, although not a legionary, expressed this situation well:

Apion to Epimachus his father and lord, very many greetings. First of all I pray for your good health and that you may always be strong and fortunate, along with my sister, her daughter, and my brother … Everything is going well for me. So, I ask you, my lord and father, to write me a letter, first about your welfare, secondly about that of my brother and sister, and thirdly so that I can do reverence to your handwriting, since you educated me well … Give all my best wishes to Capiton and my brother and sister and Serenilla and my friends. I have sent you through Euctemon a portrait of myself … (

BGU

2.423 = Campbell, no. 10)

The psychological links of family probably kept many a young man from enlisting. But the rewards awaiting were potentially great, and many others left family for a new life. In a world of chronic underemployment, a dearth of food during late winter months, and the hazards of physical disaster which could seriously disrupt the rhythm of life, the army offered the only full-time, fully employed, regularly salaried opportunity. Artemidorus took this reality and used it in his dream interpretation:

Taking up a career as a soldier portends business and employment for the unemployed and needy, for a soldier is neither unemployed, nor in want (

Dreams

2.31)