Invisible Romans (32 page)

Authors: Robert C. Knapp

This sailor’s implicit experience that service raised him from poverty was certainly shared by soldiers:

Lucius Trebius, son of Titus, father [dedicated this monument]. I, Lucius Trebius Ruso, son of Lucius, was born into abject poverty. I then served as a marine at the side of the emperor for seventeen years. I was discharged honorably. (

CIL

5.938 =

ILS

2905, Augusta Bagiennorum, Italy)

Being a soldier was considered a profession both by the soldier himself and by the civilian world. When Paul wishes to give examples of people who work at a job and deserve to be paid for it, he includes soldiers.

Who serves as a soldier at his own expense? Who plants a vineyard and does not eat of its grapes? Who tends a flock and does not drink of the milk? (1 Corinthians 9:7)

A soldier appears in Horace,

Satires

2.23–40, alongside a farmer, innkeeper, and sailor as an example of someone who works hard, looking forward to a retirement. And the possibilities for material gain were manifold. First of all there was the paid salary. A soldier made about a good daily wage for a laborer in the civilian world – but he made this every day of the year whereas the civilian laborer was often unemployed, underemployment being the norm for the ancient world as a whole at all times. Despite stoppages of various sorts and spending by soldiers, documents from Egypt indicate that as much as 25 percent of annual pay was saved. As a soldier continued in service he might well advance in grade, and with such advancement came higher salary – usually 1.5 times and sometimes twice the common soldier’s pay; if one was promoted to be a centurion – admittedly a rare event – pay was perhaps fifteen times the raw recruit’s. In addition, under the emperor Septimius Severus, all soldiers’ pay doubled. If soldiers were transferred, they received a travel allowance (

viaticum);

if they were led on a long march, they got ‘boot nail money’ (

clavarium),

the residue of which would also be put into the savings bank. Then there were the periodic liberalities from the reigning emperor. These donatives were paid directly to the soldiers on a pro rata basis determined by the grade in the army. In addition, upon the death of an emperor, soldiers could expect a bequest to reach them. Finally, at discharge the soldier was paid a bonus. At first this bonus was paid in land, but the combination

of a lack of suitable land and complaints from soldiers about being, in essence, cheated through distribution of poor and distant land led to the substitution of a monetary bonus. This deposited money and bonus were not under the control of the soldier’s father according to a rule going all the way back to Augustus. In fact, the jurists were very clear that being a soldier meant that the most important aspect of a father’s power over his son was severely attenuated: whatever money a soldier acquired through being a soldier was not subject to control by his father. Not only could a father not have access to it, it could also be bequeathed independently of a father’s wishes. This provided a soldier with an economic freedom unheard of in the civilian population.

Besides monetary gain, the soldier looked forward to special privileges at law. In his private life, the soldier could, as I noted, make a will independent of his father’s wishes. In interpersonal relations, the essence of those privileges was that the soldier was always favored both by the circumstances of trial and legal procedures. Military courts had sole jurisdiction over soldiers; this included soldier-on-soldier crime and any acts a soldier might commit as a soldier. If a civilian made an accusation against a soldier, it was tried in the camp by a military tribunal made up of centurions. In addition, any civilian wishing to charge a soldier had to follow him; a soldier could not be charged

in absentia.

Neither could he be called to a distant venue to act as a witness. And if a soldier were away on army business, he could not be sued. If a soldier made an accusation against a civilian, it was tried in a civil court. But a soldier’s suit had precedence and had to be heard on a date set by the soldier. If a soldier were unfortunate enough to be convicted of a serious crime, he was exempt from torture, or condemnation to the mines, or hard labor; if of a capital crime, he could not be executed as a common criminal – no hanging, crucifixion, or being thrown to the wild beasts.

Considering all of this, it is not surprising that some thought of the army as a way to evade legal problems in their civilian life; after all, it would be easier to pursue a suit or fight one if enjoying military privileges. A third-century jurist addresses this sort of scam:

Not everyone who joins the army because he has a lawsuit pending should then be cashiered, but rather only those who join up having the court case specifically in mind, doing so to make himself more formidable to his adversary through military privileges. A person who enlists while engaged in litigation should be carefully scrutinized: If he gives up the litigation, leniency is in order, however. (Arrius Menander,

On Military Matters

1 =

Digest

49.16.4.8)

Such shenanigans were only to be expected; faking the privileged position of soldiers was a tempting route to success at law.

There were also disabilities at law that a soldier suffered, for example he could not accept gifts of items that were in litigation; he could not act as an agent for third parties; and he could not purchase land in the province where he was serving (a prohibition evidently evaded with regularity). But these were minor indeed compared to the advantages. It is easy to see why recruits were not hard to find.

Enrollment and training

Upon presentation to the recruitment officers, a recruit’s vital record was taken. This was simply his first name, family name, father’s first name, surname (

cognomen)

if he had one, voting district, place of birth or origin, and the date of enlistment. It is notable that age was not taken down. The date of enlistment was crucial, however, for from that date was figured the years of service required before discharge. That date must have been a part of the permanent record that followed the soldier, for dead servicemen much more regularly give the number of their

stipendia

– years of service – on their tombstones than they do their age.

Finding a mind uncontaminated by fancy ideas (

simplicitas)

as well as steeped in ignorance (

imperitia)

was relatively easy. Finding recruits with a useful skill was another matter. Smiths, carpenters, butchers, and huntsmen were, according to Vegetius 1.7, examples of the sort of expertise the army could use; men coming into service already trained were highly valued.

After a trial period during which the recruitment officers determined if the recruit had the proper physical and mental attitude to become a good soldier, the man was officially inducted. He was given the ‘military mark’ – an indelible brand or tattoo on the hand – and then posted to a legion, where basic training took place for the first four or five months. Initiated into the legion, the soldier began a new way of life.

If he came illiterate, and most would, he found that the life of the army was to an astonishing degree paper driven. All sorts of records were kept on a daily and annual basis and required literacy of a number of soldiers. Especially if one wanted to advance, the ability to read, write, and do sums was essential. Vegetius 2.19 notes that literate recruits were sought:

The army seeks in all its recruits tall, robust, quick-spirited men. But since there are many administrative units in the legions that need literate soldiers, those who can write, count, and calculate are preferred. For the entire record-keeping of the legion, whether of obligations or military fatigues or finances, is noted down in the daily records with even greater care than the taxes-in-kind accounts or the records of various sorts kept in the civilian world.

In Vindolanda, near Hadrian’s Wall, writing tablets were found that because of their unusual preservation environment could still be read. These tablets showed literacy among not only unit leaders such as centurions and decurions, but also rankers. One scholar even claims these show greater general literacy than in the civilian population. Even if a soldier came illiterate, he might learn on the job. For those, a rough ‘military’ literacy was probably all they ever possessed; the literate, literary, cultured world of the officer class remained inaccessible to them.

On a daily basis there was enough food to eat. There were no nonmilitary persons except, perhaps, for families of officers and of a few soldiers (see below). The prevalence of small-time thieves and hooligans that cursed civilian towns was totally absent; what little crime there was would be soldier-on-soldier. But it is perhaps in sanitary conditions, medical care, exercise, and general concern for good health that the soldier’s life benefited the most. In the army, every large encampment had a bath complex that provided a place for less-structured exercise as well as some cleanliness. Engineered latrines with flushing water flowing through got rid of the human waste, care being taken to discharge this into a river or lake away from where water was taken for the legion. Vegetius writes:

Now I will give advice about something which must at all cost be looked to: how the health of the army can be protected … The army should not use bad or swampy water, for drinking bad water is like taking poison and makes those drinking it ill. And indeed when a common soldier falls ill, all officers, from the lowest to the commander of the legion, should do his utmost to see that he is made well with proper diet and medical attention. For it will go badly for soldiers who must deal with both the demands of war and of disease. But it should be noted that military experts agree: daily exercise at arms leads more to the health of the soldiers than anything the doctors can do. (

On Military Affairs

3.2)

While the goals of Vegetius might not always have been met, the soldier was better fed, and lived in a decidedly cleaner, better-aired environment that was better equipped with sanitary facilities, than the population at large.

Life in the camp

Most of army life is a routine of sleeping, eating, fatigues (i.e. daily, menial chores around the camp), and drilling. It was crucial that the legion operate efficiently as a unit and obey commands unquestioningly. This was achieved by constant exercises. For recruits, twice-daily drills were the order; for experienced soldiers, once daily. Here the soldiers learned to move as a body through practicing marching and maneuvers; they learned how to use their weapons, the shield, the sword, and the spear; they built up endurance so they could march long distances daily with heavy packs. They also apparently took care of their own sanitation and other needs, having latrine details and such like.

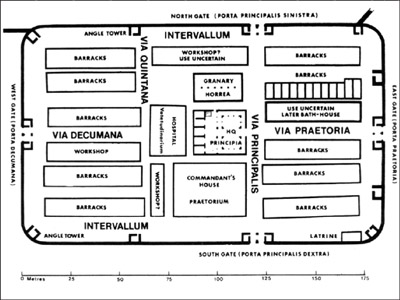

Barracks provided living space for each soldier. Soldiers lived together in their units: each barrack had a larger room with its own antechamber for the centurion, and eight to ten rooms for a

contubernium

of eight men. Each

contubernium

room was divided into an anteroom and sleeping chamber. It is certain that a centurion could have his mate (and, presumably, children) living in the camp with him; although there is evidence that some soldiers did as well in a few camps, the norm was to have only the men in the camp itself; ‘wives’ lived outside with the family, visited regularly by the soldier who had to live in the camp itself.

This living situation might seem cramped, but it was probably no less private that most civilian living conditions for ordinary folk. The sense of comradeship inherent in this dormitory life was enhanced by the fact that the unit prepared its own food and ate together – there was no mess hall and central kitchen, except, perhaps, for the ovens to bake bread.

17. A Roman fort. This plan of the Housesteads fort on Hadrian’s Wall in northern England is arranged in a typical fashion. The soldiers’ barracks are on the left and right sides, the commander’s place in the lower center.

Medical treatment for the Roman population as a whole was a rather hit-and-miss affair. The first recourse for any ailment was home cures, whether at the hands of family members or local ‘experts’ in the community. Doctors were professionals who had to be paid; although the elite used them extensively, access to them was limited for large portions of the population. In the army, though, loss of manpower through disease or injury was taken very seriously. As in armies down to modern times, more losses were incurred through physical disabilities than through warfare itself. Doctors needed to be at hand to treat wounds but also,

more regularly, diseases and injuries incurred in the line of duty outside of warfare itself. Although medical practice was a curious mixture of invasive actions (surgery, etc.), harmful procedures, home cures (diet, exercise, adequate sleep, etc.), drugs, and prayers, it constituted the best the Roman world had to offer. A well-trained doctor had at least a better chance of diagnosing properly an affliction and so increasing the chances of offering effective cure. I would suppose, although no proof is possible, that more men survived through being treated by doctors than would have if left to their own devices.