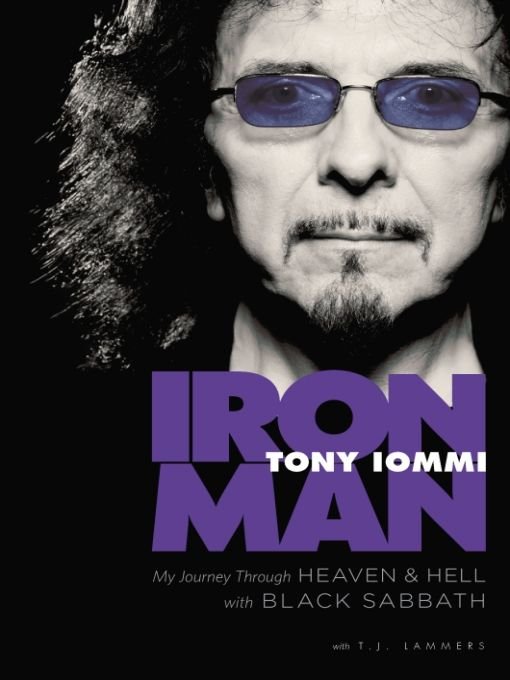

Iron Man

Authors: Tony Iommi

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

I dedicate this book to Maria; my wife and soulmate.

My daughter Toni, for being the best daughter

any man could ever have.

any man could ever have.

My late Mom and Dad, for giving me life.

Introduction:

The Sound of Heavy Metal

It was 1965, I was seventeen years old, and it was my very last day on the job. I'd done all sorts of things since leaving school at fifteen. I worked as a plumber for three or four days. Then I packed that in. I worked as a treadmiller, making rings with a screw that you put around rubber pipes to close them up, but that cut up my hands. I got a job in a music shop, because I was a guitarist and played in local bands, but they accused me of stealing. I didn't do it, but to hell with them: they had me cleaning the storeroom all day anyway. I was working as a welder at a sheet-metal factory when I got my big break: my new band, The Birds & The Bees, were booked for a tour of Europe. I hadn't actually played live with The Birds & The Bees, mind you; I'd just auditioned after my previous band, The Rockin' Chevrolets, had hoofed out their rhythm guitarist and subsequently broken up. The Rockin' Chevrolets had been my first break. We wore matching red lamé suits and played old rock 'n' roll like Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. We were popular around my hometown of Birmingham, and played regular gigs. I even got my first serious girlfriend out of that band, Margareth Meredith, the sister of the original guitarist.

The Rockin' Chevrolets were fun, but playing in Europe with

The Birds & The Bees, that was a real professional turn. So I went home for lunch on Friday, my last day as a welder, and said to my mum: âI'm not going back. I'm finished with that job.'

The Birds & The Bees, that was a real professional turn. So I went home for lunch on Friday, my last day as a welder, and said to my mum: âI'm not going back. I'm finished with that job.'

But she insisted: âIommis don't quit. You want to go back and finish the day off, finish it proper!'

So I did. I went back to work. There was a lady next to me on the line who bent pieces of metal on a machine, then sent the pieces down to me to weld together. That was my job. But the woman didn't come in that day, so they put me on her machine. It was a big guillotine press with a wobbly foot pedal. You'd pull a sheet of metal in and put your foot on the pedal and, bang, a giant industrial press would slam down and bend the metal.

I'd never used the thing before, but things went all right until I lost concentration for a moment, maybe dreaming about being on stage in Europe and, bang, the press slammed straight down on my right hand. I pulled my hand back as a reflex and the bloody press pulled the ends off my two middle fingers. I looked down and the bones were sticking out. Then I just saw blood going everywhere.

They took me to hospital, sat me down, put my hand in a bag and forgot about me. I thought I'd bleed to death. When someone thoughtfully brought my fingertips to hospital (in a matchbox) the doctors tried to graft them back on. But it was too late: they'd turned black. So instead they took skin from one of my arms and grafted it on to the tips of my wounded fingers. They fiddled around a bit more to try to ensure the skin graft would take, and that was it: rock 'n' roll history was made.

Or that's what some people say, anyway. They credit the loss of my fingers with the deeper, down-tuned sound of Black Sabbath, which in turn became the template for most of the heavy music created since. I admit, it hurt like hell to play guitar straight on the bones of my severed fingers, and I had to reinvent my style of

playing to accommodate the pain. In the process, Black Sabbath started to sound like no band before it â or since, really. But creating heavy metal because of my fingers? Well, that's too bloody much.

playing to accommodate the pain. In the process, Black Sabbath started to sound like no band before it â or since, really. But creating heavy metal because of my fingers? Well, that's too bloody much.

After all, there's a lot more to the story than that.

1

The birth of a Cub

Of course, I wasn't born into heavy metal. As a matter of fact, in my first years I preferred ice cream â because at the time my parents lived over my grandfather's ice cream shop: Iommi's Ices. My grandfather and his wife, who I called Papa and Nan, had moved from Italy to England, looking for a better future by opening an ice cream business over here. It was probably a little factory, but to me it was huge, all these big stainless steel barrels in which the ice cream was being churned. It was great. I could just go in and help myself. I've never tasted anything that good since.

I was born on Thursday 19 February 1948 in Heathfield Road Hospital, just outside Birmingham city centre, the only child of Anthony Frank and Sylvie Maria Iommi, née Valenti. My mother had been in hospital for two months with toxaemia before I appeared; was this a sign of things to come she might have felt! Mum was born in Palermo, in Italy, one of three children, to a family of vineyard owners. I never knew my mum's mother. Her father used to come to the house once a week, but when you're young you don't hang around sitting there with the old folks, so I never knew him that well.

Papa on the other hand was very good natured and generous

and as well as giving money to help the local kids he'd always hand me half a crown when I came to see him. And some ice cream. And salami. And pasta. So you can imagine I loved visiting him. He was also very religious. He went to church all the time and he sent flowers and supplies over there every week.

and as well as giving money to help the local kids he'd always hand me half a crown when I came to see him. And some ice cream. And salami. And pasta. So you can imagine I loved visiting him. He was also very religious. He went to church all the time and he sent flowers and supplies over there every week.

I think my nan was from Brazil. My father was born here. He had five brothers and two sisters. My parents were Catholic, but I've only seen them go to church once or twice. It's strange that my dad wasn't as religious as his father, but he was probably like me. I hardly ever go to church either. I wouldn't even know what to do there. I actually do believe in a God, but I don't go to church to press the point.

My parents worked in a shop that Papa had given them as a wedding present, in Cardigan Street in Birmingham's Italian quarter. As well as the ice-cream factory, Papa owned other shops and he used to have a fleet of mobile baking machines. They'd go into town, set up and sell baked potatoes and chestnuts, whatever was in season. My dad was also a carpenter and a very good one at that; he made all our furniture.

When I was about five or six we moved away from ice-cream heaven to a place in Bennetts Road, in an area called Washwood Heath, which is part of Saltley, which in turn is a part of Birmingham. We had a tiny living room with a staircase going up to the bedroom. One of my earliest memories is of my mother carrying me down these steep stairs. She slipped and I went flying and, of course, landed on my head. That's probably why I am like I am . . .

I was always playing with my lead soldiers. I had a set of those and little tanks and so on. As a carpenter my dad was away a lot, building Cheltenham Racecourse. Whenever he came back home he'd bring me something, like a vehicle, adding to the collection.

When I was a kid I was always frightened of things, so I'd get under the blanket and shine a little light. Like a lot of kids do. My

daughter was the same. Just like me, she couldn't sleep without the light on, and we'd have to keep her bedroom door open. Like father, like daughter.

daughter was the same. Just like me, she couldn't sleep without the light on, and we'd have to keep her bedroom door open. Like father, like daughter.

Other books

Deathless Love by Renee Rose

The Girl in the Glass Tower by Elizabeth Fremantle

Dark Homecoming by William Patterson

Malarkey by Sheila Simonson

Some Desperate Glory by Max Egremont

The Twelve Dates of Christmas by Catherine Hapka

We'll Meet Again by Mary Higgins Clark

Consenting Adult by Laura Z. Hobson

Bound, Branded, & Brazen by Jaci Burton

The Strawberry Sisters by Candy Harper