Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (13 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

As Jane Grigson reminds us, to make good potato cakes we need floury potatoes, and in our islands, even in the other one, they’re rarities now. All the same, at the Kundan restaurant in Horseferry Road, Westminster, admirably cooked and wonderfully spiced potato cakes are always to be had, and I don’t believe the kitchen there has any potatoes we can’t all buy. Admittedly, to order Kundan’s potato cakes you ask for vegetable kebabs, but the point is that they

can

be ordered, that they will arrive freshly made, sizzling in an iron pan, and you may eat them on their own. You aren’t expected to have them

with

something.

I didn’t intend to give the impression that Jane Grigson’s

British Cookery

is exclusively concerned with potatoes – indeed I rather wish she’d given more space to the subject, potatoes being, after all, of nearly as much national interest as grain and bread – because what this new book is really about is not so much British cooking as its essential materials and the heroic efforts currently being made by British market-gardeners, fruit growers, poultry and livestock-breeders – one success there is the rearing of veal calves in decent, humane conditions – British dairy farmers and British cheesemakers. With the very properly acknowledged assistance of Major Patrick Rance of cheese-shop fame, and with the co-operation of a handful of conscientious restaurateurs and retailers, Jane Grigson has sought out dedicated small-scale producers who are constructively fighting the familiar ogres of factory farming, unworkable EEC regulations, the bureaucrats of the Milk Marketing Board and all those who push the just acceptable at the expense of the best. An appendix lists relevant addresses.

When it comes to honourable British specialities Jane Grigson knocks spots off our feeble Taste of Britain campaigns with their make-believe food and phoney regional recipes. Here, for a start, is that legendary rarity, the Lincolnshire chine of salt pork stuffed with a basinful of fresh green herbs of all sorts. Tied in a cloth, boiled, pressed, eaten cold, the Lincoln chine was described, with much relish, by the poet Verlaine when a schoolmaster in the locality in the 1870s. I suppose you could say it is England’s reply to the Burgundian

jambon persillé

. An appetising photograph of

this appetising speciality accompanies the recipe, and Mrs Grigson gives the address of the Lincoln butcher from whom it may be ordered, May to December.

Inevitably, in a book with origins in a chopped-up Sunday supplement series, the photographs of sheep farmers, cheesemakers, shopkeepers, seaweed gatherers tend to look folksy and contrived as though the subjects were posing for postcards. Come to that, the

Observer

could do worse than go into the food postcard business – I’ve often thought of doing it myself – donating a proportion of the profits to the support of some worthy cause. How about a campaign to outlaw the use of dye in the cure of smoked haddock and kippers? Or promotion of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, a body helping for one thing, to bring back real ham pigs such as the Tamworths and Gloucester Old Spots reared by Anne Petch of Heal Farm, King’s Nympton, Devon? From these pigs Mrs Petch cures hams described by Mrs Grigson as glorious, no less.

Tatler

, March 1985

In the 1980s Jane Grigson, and other writers and broadcasters like Jeremy Round and Derek Cooper did their utmost to raise awareness of and promote the best of British produce. The Consumers’ Association published its

Good Food Directory

, edited by Drew Smith and David Mabey, in 1986. In 1993 appeared the first edition of Henrietta Green’s influential

Food Lover’s Guide to Britain

, and by then Randolph Hodgson and his colleagues at Neal’s Yard Dairy had further developed the market for prime British cheeses. At the end of the 1990s farmers’ markets were being established across Britain, and specialist and organic producers of meat, fish, fruit and vegetables are doing booming business by mail order as well as through supermarkets and independent shops.

JN

The Great English Aphrodisiac

It was a subject awaiting an author. The potato, its history as a member of the botanical family

Solanaceae

, its adoption by man as a cultivated plant, and the record of its spread throughout the

world, found a very remarkable author. He was a young doctor, whose active career in medicine had been cut short by illness while still in his twenties. By the time he was thirty-two, living a life of ease in a beautiful Hertfordshire village, happily married, free from financial worries, Redcliffe Salaman found himself completely restored to health and able once more to lead a physically active life. His winters were sufficiently taken up with fox-hunting but, lacking enthusiasm for golf, tennis and cricket, he found his summers empty of interesting occupation. After a false start in the field of Mendelian research and the study of the heredity of butterflies, hairless mice, guinea pigs and the like, this singular young man turned to his gardener for advice as to a suitable subject for research. Something ordinary, such as a common kitchen garden vegetable, Dr Salaman stipulated.

The gardener, whose name was Evan Jones, was that archetype, the omniscient one known ever since Adam vacated Eden. Jones had no hesitation in advising Dr Salaman that if he wanted to spend his spare time in the study of vegetables, then he had better choose the potato. Because, said Jones, ‘I know more about the potato than any man living.’ It was then 1906. Forty-three years later, in 1949, Redcliffe Salaman’s extraordinary study,

The History and Social Influence of the Potato

, was published by the Cambridge University Press. ‘A work of profound and accurate scholarship’, commented the scientific journal

Nature

. ‘A great, in many respects a noble work’ was the

Spectator

’s verdict. Reprinted in 1970, and again last November, with a new introduction and corrections by J. G. Hawkes, the book remains a major work of reference on its subject.

With the exception of recipes, no aspect of the potato story was neglected by Salaman. He traces its origins in the Andes, and its deep significance in the lives of the Incas, to its arrival and reception in Europe in the second part of the sixteenth century, its fatal planting and all too rapid spread in Ireland, its entirely mythical connection with Virginia, the long unresolved confusion of identity between the tubers of the sweet potato,

Ipomoea batatas

, and those of the totally unrelated common potato,

Solanum tuberosum

, further complicated by the late arrival in Europe of a red herring in the shape of

Helianthus tuberosus

, known to us as the Jerusalem artichoke, to the French as

topinambour

, and to the Germans as

Erdbirn

or earth pear. In France arose an even odder confusion created apparently by the French horticulturalist

Olivier de Serres who, in 1600, published his

Théâtre d’Agriculture

in which he offered a description of the potato plant comparing its tubers to truffles, saying that it was often called by the same name,

cartouffles

. As to the taste, said de Serres, ‘The cook so dresses all of them that one can recognise but little difference between them.’

Olivier de Serres was not alone in likening potatoes to truffles. To the Italians at the same period, common potato tubers were

tartuffoli

or

taratouffli

, and under the latter name two were sent by a correspondent to the famous Belgian-born botanist Charles de L’Ecluse in Vienna, where in 1588 he was employed working on the Emperor Maximilian’s gardens. A few years later, in 1595, L’Ecluse, or Clusius as he called himself in Latin, accepted a professorship at Leyden University, and from then until his death in 1609 one of his many preoccupations was the encouragement of potato cultivation – of the common potato, that is – throughout Europe.

At the same time – although Salaman does not specifically point this out – to most Italian contemporaries of Olivier de Serres and Charles de L’Ecluse, potatoes undoubtedly meant

patatas

or sweet potatoes, not the common potato. In Spain, particularly around Seville and Malaga,

patatas

had been established early in the sixteenth century. It was probably from Spain, therefore, that they reached Italy. In both countries they were appreciated for their sweetness and the resemblance of their flesh to that of sweet chestnuts, which at the time were commonly served with the dessert fruits. Roasted in the ashes, peeled, sugared, sliced into white wine, or into a sugar-syrup, potatoes were also candied, as in those days was almost every fruit, vegetable and flower in sight, from primroses to pumpkins, lettuce stalks to wild cherries. In 1557, a Spanish writer, G. F. Oviedo y Valdes, giving an account of Hispaniola (Haiti), compared

patatas

favourably to marzipan. A higher recommendation you could not give.

In England, too, potatoes imported from Spain were quickly accepted as a delicacy. They wouldn’t, of course, grow in the English climate, and the price was high. Salaman cites an instance of two pounds of potatoes ‘for the Queen’s table’ costing, in 1599, 2s 6d per pound. Regardless of price, or perhaps because of it, they took the fancy of the luxury-loving Tudor gentry. Recipes for candying potatoes were tried out and written down in household receipt books, and before long the tubers were

appearing as an ingredient in expensive pie fillings. A receipt for one such found its way into print in a little book promisingly titled

The Good Huswife’s Jewell

published as early as 1596. Thomas Dawson, who claimed authorship of the book, gave the ingredients as two quinces, two or three burre roots (pears, says Salaman. But why roots?), an ounce of dates and just one ‘potaton’, cooked in wine, sieved, mixed with rosewater, sugar, spices, butter, the brains of three or four cock-sparrows and eight egg yolks, all to be cooked until thick enough to be consigned to the pastry case. If the sparrows’ brains and the potaton didn’t give the game away, the title of the receipt was clear enough. ‘To make a tarte that is a courage to a man or woman’ simply meant that the brew was an aphrodisiac, although just why sparrows’ brains were so associated I have never discovered. How the Spanish potato came to join the list of prized English aphrodisiacs is explained by Salaman in a diverting chapter, one which he himself had clearly had a good deal of fun researching.

In the works of late Elizabethan and early Jacobean dramatists, including Shakespeare, Salaman found quite a storehouse of bawdry concerning the perfectly innocent Spanish tubers. They were of course luxuries. As such they came to have the same saucy connotation as champagne, caviar, oysters and truffles to later generations. In 1617 potatoes were included among the foods dubbed ‘whetstones of venery’ by George Chapman. In the same year, John Fletcher had soldiers disguised as pedlars singing licentious songs and making impudent fun of an elderly gentleman: ‘Will your Lordship please to taste a fine potato? T’will advance your withered state. Fill your Honour full of noble itches.’

In only slightly less crude terms Fletcher, again, suggests the potato as revivifier of a woman’s lost vigour: ‘Will your Ladyship have a potato pie? T’is a good stirring dish for an old lady after a long Lent.’ Not that everyone thought it necessary to abstain from this over-stimulating food during Lent. In 1634 the prolific early Stuart letter-writer, James Howell, castigated people who while abstaining from ‘Flesh, Fowl and Fish’ on Ash Wednesday, made up for the penance by eating luxurious ‘Potatoes in a dish Done O’er with Amber, or a mess of Ringos in a Spanish dress’. Ringos were eryngoes, roots of the sea-holly, usually candied, and had long preceded the potato as a reputed aphrodisiac.

The absurdest aspect of the aphrodisiac story was that when eventually the common potato,

Solanum tuberosum

, superceded

Ipomoea batatas

in English esteem, the reputation of the exotic Spanish potato was for a time transferred to our own home-grown tuber. In continental Europe the aubergine and the tomato, both members of the same

Solanaceae

family, were in their turn attributed with the possession of aphrodisiac powers.

Tatler

, May 1985

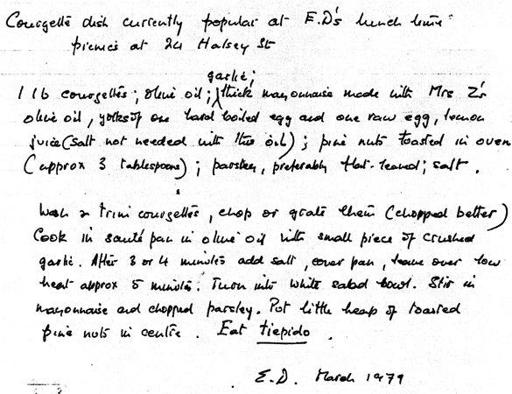

This courgette dish is one I remember eating on several occasions, and very good it was too. Elizabeth often gave typed or occasionally handwritten recipes, signed and dated, to her friends, to celebrate a birthday or as a memento of a meal. Sometimes there were different versions of a dish as she evolved and tested recipes further. In her

note to Lesley O’Malley following the Fish Loaf (

page 160

) she makes it clear that the ingredients for the dish could be varied in many ways.

The olive oil referred to above was produced by Mrs Zyw in Tuscany, and in the days of the kitchen shop, sold there, and subsequently by the wine merchants, Haynes, Hanson and Clark.

500 g (1 lb) courgettes should be used for this dish, and the instructions for making mayonnaise are on

page 122

.