Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (3 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

As demonstrated by Nanny’s surreptitious nursery cooking, what you can cook on a stove in a passage or on a staircase landing, or over a gas ring or small open fire, is fairly surprising. Granted, the will to do it, plus a spirit of enterprise and a little imagination, are necessary elements in learning to cook. You have to have a healthy appetite, too, and not worry too much over the failures or shortcomings of your kitchen and its equipment.

During the war years in Egypt, when I ran a reference library for the British Ministry of Information, I lived in a ground floor flat located in a car park for the vehicles used by one of the secret service organisations whose offices, in a nearby building, were known to every cab driver in Cairo as The Secret House. My cook, a Sudanese called Suleiman, performed minor miracles with two Primus stoves and an oven which was little more than a tin box perched on top of them. His soufflés were never less than successful, and with the aid of a portable charcoal grill carried across the road to the Nile bank opposite (the kitchen was so small it didn’t even have a window, and if he had used charcoal he’d have been asphyxiated), he produced perfectly good lamb kebabs. The rice pilaff I named after him and the recipe for it which I published in my first book in 1950, became part of quite a few people’s lives at that time. When something was lacking in my kitchen, which was just about every time anyone came to dinner, Suleiman would borrow it from some grander establishment. All Cairo cooks did likewise. Thus a dinner guest was quite likely to recognise his own plates, cutlery or serving dishes on my table. Nobody commented on this familiar custom.

In Cairo and Alexandria, ice was easy to come by – although I never thought, in those days, to ask where it came from, I now know that there were flourishing ice factories in Egypt – and so

from an old hand-cranked churn on loan for the evening, Suleiman would produce delectable ice-creams. At that time, Groppi’s, the famous Cairo café, was well known for its ices, although those at Baudrot’s in Alexandria were even better, and many of the hospitable local families employed cooks who made fine ices, so there was plenty of competition. All the same, it would have been hard to beat Suleiman’s home-made

mish-mish

or apricot ice-cream. The only drawback was the cranking of the churn, which made so much noise that it tended to bring dinner-table conversation to a standstill.

My Cairo kitchen, absurdly inadequate though it was, is one I remember with some affection. I couldn’t now contemplate cooking in such a hole in the wall, nor indeed did I then, except on rare occasions when I took it into my head to show Suliman how to cook something I had learned in France or Greece before the war, but all the same some memorable food came out of that kitchen, including one year even a Christmas pudding. This pudding Suleiman, too hastily briefed by me, very understandably supposed was a main course to be served after the soup, and bore it in flaming according to my instructions. Crestfallen, he took it away, but brought it back again at the appropriate moment, in undiminished style, once more drenched in rum and distinctly more alcoholic than was quite orthodox.

After the war, when I returned to a drastically rationed and chilly England, my first kitchen was in a furnished flat in Kensington. It was one of those in which the table was also the cover of the bath. There was a gas cooker, a very small Electrolux fridge – a blessing which I certainly appreciated, given that such things were then in very short supply – and a sink. There wasn’t much room for equipment, but I didn’t have much because most of my belongings, including my big, old fridge, had been destroyed in a store which had been hit by a bomb. Still, with such ingredients as I could find, rationed and unrationed, I cooked a lot. In those days there weren’t many London restaurants one wanted to go to or indeed could afford, and I was thankful to have learned a little about cooking foods such as lentils and beans which weren’t either rationed or totally unobtainable. Rice, alas, was one of the latter commodities, and was not to return for another year. Lemons were still scarce, but after a long absence tomatoes reappeared, and the Italian shops in Soho began to sell real spaghetti and olive oil. Butter, eggs and milk remained on ration for many

years, but there was bootleg cream and butter from Ireland, and eggs from a farm in Wales. We all learned to make the best of what we could get.

As for that squalid kitchen/bathroom arrangement, it did at least keep clutter at bay. If you have to clear your kitchen table every morning before you can have a bath, you do tend to put things back in their proper places. I hate clutter in the kitchen. Not that that means I don’t live with it. There are some people, and I have to recognise that I’m one of them, who if they had a kitchen the size of the Albert Hall would still contrive to be surrounded by clutter. But as long as I have plenty of cupboards, spacious wooden draining-boards, a deep, roomy sink – porcelain, none of your tinny stainless steel – and a wooden, not a plastic, plate rack which takes serving dishes as well as plates and cups and saucers, oh, and of course a large fridge (actually I have two), I suppose I don’t have any excuse for clutter. I am not advising anyone to follow my example. It’s not a good one.

Smallbone of Devizes’ catalogue, Summer 1989

Elizabeth David’s ‘Dream’ Kitchen

So frequently do dream kitchens figure in the popular newspaper competitions, in the pages of shiny magazines and in department store advertising that one almost begins to believe women really do spend half their days dreaming about laminated work-tops, louvered cupboard doors and sheaves of gladioli standing on top of the dishwasher. Why of all rooms in the house does the kitchen have to be a dream? Is it because in the past kitchens have mostly been so underprivileged, so dingy and inconvenient? We don’t, for example, hear much of dream drawing-rooms, dream bedrooms, dream garages, dream boxrooms (I could do with a couple of those). No. It’s a dream kitchen or nothing. My own kitchen is rather more of a nightmare than a dream, but I’m stuck with it. However, I’ll stretch a point and make it a good dream for a change. Here goes.

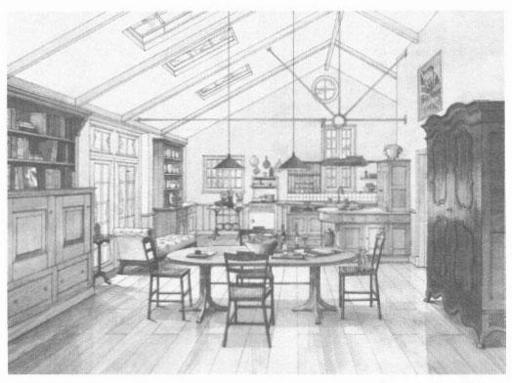

This fantasy kitchen will be large, very light, very airy, calm and warm. There will be the minimum of paraphernalia in sight.

It will start off and will remain rigorously orderly. That takes care of just a few desirable attributes my present kitchen doesn’t have. Naturally there’ll be, as now, a few of those implements in constant use – ladles, a sieve or two, whisks, tasting spoons – hanging by the cooker, essential knives accessible in a rack, and wooden spoons in a jar. But half a dozen would be enough, not thirty-five as there are now. Cookery writers are particularly vulnerable to the acquisition of unnecessary clutter. I’d love to rid myself of it.

The sink will be a double one, with a solid wooden draining-board on each side. It will be (in fact, is) set 760 mm (30 in) from the ground, about 152 mm (6 in) higher than usual. I’m tall, and I didn’t want to be prematurely bent double as a result of leaning over a knee-high sink. Along the wall above the sink I envisage a continuous wooden plate rack designed to hold serving dishes as well as plates, cups and other crockery in normal use. This saves a great deal of space, and much time spent getting out and putting away. Talking of space, suspended from the ceiling would be a wooden rack or slatted shelves – such as farmhouses and even quite small cottages in parts of Wales and the Midland counties used to have for storing bread or drying out oatcakes. Here would be the parking place for papers, notebooks, magazines – all the things that usually get piled on chairs when the table has to be cleared. The table itself is, of course, crucial. It’s for writing at and for meals, as well as for kitchen tasks, so it has to have comfortable leg room. This time round I’d like it to be oval, one massive piece of scrubbable wood, on a central pedestal. Like the sink, it has to be a little higher than the average.

Outside the kitchen is my refrigerator and there it will stay. I keep it at the lowest temperature, about 4°C (40°F). I’m still amazed at the way so-called model kitchens have refrigerators next to the cooking stove. This seems to me almost as mad as having a wine rack above it. Then, failing a separate larder – in a crammed London house that’s carrying optimism a bit too far – there would be a second and fairly large refrigerator to be used for the cool storage of a variety of commodities such as coffee beans, spices, butter, cheese and eggs, which benefit from a constant temperature of say 10°C (50°F).

All the colours in the dream kitchen would be much as they

Perspective of the ‘dream’ kitchen

are now, but fresher and cleaner – cool silver, grey-blue, aluminium, with the various browns of earthenware pots and a lot of white provided by the perfectly plain china. I recoil from coloured tiles and beflowered surfaces and I don’t want a lot of things coloured avocado and tangerine. I’ll just settle for the avocados and tangerines in a bowl on the dresser. In other words, if the food and the cooking pots don’t provide enough visual interest and create their own changing patterns in a kitchen, then there’s something wrong. And too much equipment is if anything worse than too little. I don’t a bit covet the exotic gear dangling from hooks, the riot of clanking ironmongery, the armouries of knives, or the serried rank of sauté pans and all other carefully chosen symbols of culinary activity I see in so many photographs of chic kitchens. Pseuds corners, I’m afraid, many of them.

When it comes to the cooker I don’t think I need anything very fancy. My cooking is mostly on a small scale and of the kind for intimate friends, so I’m happy enough with an ordinary four-burner gas stove. Its oven has to be a good size, though, and it has to have a drop-down door. Given the space I’d have a second, quite separate oven just for bread, and perhaps some sort of temperature-controlled cupboard for proving the dough. On the whole though it’s probably best for cookery writers to use the same kind of domestic equipment as the majority of their readers. It doesn’t do to get too far away from the problems of everyday household cooking or take the easy way out with expensive gadgetry.

What it all amounts to is that for me – and I stress this is purely personal, because my requirements as a writing cook are rather different from those of one who cooks mainly for a succession of guests or for the daily meals of a big family – the perfect kitchen would really be more like a painter’s studio furnished with cooking equipment than anything conventionally accepted as a kitchen.

Article contributed to

The Kitchen Book

by Terence Conran, Mitchell Beazley, 1977

When Terence Conran initially asked to photograph the kitchen at Halsey Street for

The Kitchen Book

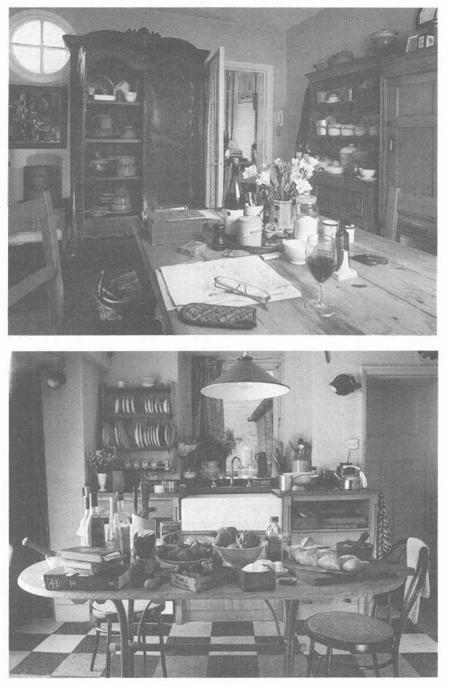

Elizabeth refused, explaining that her nephew, Johnny Grey, was designing some new furniture for the kitchen. They came up with the idea that she should write a piece for the book on her ‘dream’ kitchen. Elizabeth asked Johnny to design it with her and he drew up the plan (page 9). The kitchen she describes is in fact a larger and more orderly version of her original kitchen (upper photograph, facing); the plan shows many of the features of Elizabeth’s kitchen – the French armoire, the English dressers, the wooden plate rack next to the sink and the Cannon cooker. She also had a chaise longue in front of the French windows leading on to a small courtyard and a small round window in the opposite wall.

In the early 1980s the basement was converted into a kitchen, designed in the spirit of this plan (lower photograph, facing) and the second fridge was placed just beyond the kitchen door. The original kitchen remained as it was, but was used less.

JN

How Publishers like to have their Cake and Eat it

His glance at the typescript I had put on his desk was one of distaste, not in the least disguised.

‘It looks rather long.’

‘Does it? I suppose there was more material than I expected.’

‘You’ve certainly taken your time about it.’

‘Er, well, yes.’

Captain Eric Harvey, MC, director of the publishing firm of Macdonalds, lumbered across to his filing cabinet, extracted a folder, re-inserted himself behind his desk, scrutinised the document now before him.