Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (34 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

garlic press should not be used for this sauce. Garlic is obviously a potent ingredient. It should not be an acrid one, which it becomes when the juices only are extracted by the crushing action of the garlic press.

Marinate chicken legs or breasts for 2 hours. Legs will require 30–40 minutes to cook through, boned breasts 10–15 minutes. Cubes of pork fillet marinaded in the same mixture and grilled on skewers are perhaps even more successful than chicken. Grill for 20 minutes.

Twelve cloves of garlic may sound overpowering. Curiously enough, by the time the sauce has been, as it were, distributed among the pieces of meat or chicken, it is by no means too strong, and meat with a tendency to dryness is much benefited by the

combined flavours as well as by the action on it of the constituents of the marinade.

Unpublished, 1970s

POULET ROBERT

This is a Norman chicken dish – one for a special treat for 2 or 3 people – and although it comes from only just across the Channel it has a wonderfully unfamiliar flavour.

For a roasting chicken weighing approximately 1.2 kg (2½ lb), the other ingredients are 45 g (1½ oz) butter, 2 tablespoons olive oil, 1 onion, 60 g (2 oz) ham, a teaspoon of chopped tarragon or celery leaves, 150 ml (¼ pint) of white table wine or medium dry still cider, a teaspoon of strong yellow mustard, salt, freshly milled pepper, and 4 tablespoons of Calvados. This last is the celebrated and potent Norman spirit distilled from cider, but our own native whisky can be used instead – it’s a better substitute in this case than cognac.

In a heavy cast-iron pot in which the chicken will fit neatly, heat the butter and oil and in it melt the sliced onion with the chopped ham. Add the neck, heart and gizzard and then the chicken, seasoned inside with salt, pepper and the tarragon or celery. Let it brown gently on both sides.

In a soup ladle or small saucepan warm the Calvados or whisky and set light to it. Pour it blazing over the chicken, at the same time turning up the heat and tilting the pot from side to side until the flames have burned out. Then add the wine or cider. Let it bubble for two or three minutes. Cover the pot with its lid. Simmer steadily, not too fast, for 20 minutes. Turn the chicken over. Cook another 20 minutes. Remove the chicken. Extract the giblets. Let the remaining sauce boil fast while you quickly joint the bird.

Finally, having stirred the mustard into the sauce, pour it with all its delicious little bits of ham and onion, into a warmed serving dish, which should be about as deep as an old-fashioned soup plate – there isn’t a lot of sauce but what there is has an intense and rich flavour – and put the pieces of chicken on top. Scatter a little parsley over it. The accompaniment to this dish should be either 2 dessert apples, peeled, cubed and fried in butter; or plain little new potatoes; or 250 g (½ lb) of small sliced mushrooms

cooked in butter. No green vegetable – but most decidedly a fresh crisp green salad.

If you have to keep the chicken waiting while a first course is being eaten, then place your dish, covered, over a saucepan of gently simmering water. This is a better system than putting it into the oven, where the sauce would go on cooking and the butter and liquid would separate, leaving rather a messy mixture.

From a pamphlet written for Le Creuset, late 1960s

BIANCO-MANGIARE

A kind of cold chicken pâté.

300–375 g (10–12 oz) cooked chicken, weighed without skin and bone

60 g (2 oz) almonds, skinned

2 eggs

150 ml (¼ pint) cream

2 tablespoons rosewater

3 tiny slices green ginger

salt, sugar

for decorating

: pine nuts or split almonds

Almonds to be ground very fine.

Chicken in grinder with rosewater, ginger, sugar, very little salt.

Stir in almonds.

Beat in eggs. Fold in cream. Add more salt if necessary.

Turn into non-stick loaf tin. Cover with foil.

Cook in a bain-marie, 170°C/325°F/gas mark 3, below the centre, for 50 minutes.

Cool and put into the fridge.

Next day turn out. Stand the tin in a little cold water for a few minutes before inverting it on to the dish. After a sharp tap or two with a knife handle the pâté should slide out easily.

Stick toasted pine nuts or almond slivers upright all over, like a hedgehog.

This is a manuscript recipe, written in note form, for Elizabeth’s friend Lesley O’Malley, probably in the 1970s. The information is indeed brief, but to the point; you are told when to add each ingredient, and

how. Most importantly, you are told at what temperature and for how long to cook the bianco-mangiare. JN

DUCK BAKED IN CIDER

Rub a 3 kg (6 lb) duck thoroughly with about 125 g (¼ lb) of coarse salt; leave it with its salt in a deep dish for 24 hours, turning it once or twice and rubbing the salt well in. To cook it, wash off the salt with cold water.

In a deep baking dish or enamelled tin with a cover (such as a self-basting roasting pan) put a couple of carrots, an unpeeled onion, a clove of garlic, a bouquet of herbs, and the giblets but not the liver of the duck. Place the duck on top of the vegetables, pour over about 450 ml (¾ pint) of dry vintage cider, and then fill up with water barely to cover the duck. Put the lid on the pan, stand this pan in a tin of water, cook in a very slow oven (150°C/300°F/gas mark 2) for just about 2 hours.

If to be served hot, take the cover off the pan during the final 15 minutes cooking, so that the skin of the duck is baked a beautiful pale golden-brown. If to be served cold, which is perhaps even better, leave it to cool for half an hour or so in its cooking liquid before taking it out.

The flavour of this duck is so good that only the simplest of salads is required to go with it.

The stock, strained, with fat removed, makes a splendid basis for mushroom or lentil soup, or for onion soup.

Unpublished, 1960s

PARTRIDGES STEWED IN MILK

For 4 stewing partridges the other ingredients are 90 g (3 oz) of butter, 750 ml (1¼ pints) of milk, 600 ml (1 pint) of water, 3 level tablespoons of flour, seasonings.

Brown the birds gently in the butter in a heavy and fairly deep stewing pot. Over them pour 600 ml (1 pint) of the milk, hot, and the water, also hot. When the liquid reaches simmering point, cover the pot, transfer it to a very low oven (150°C/300°F/gas mark 2) and leave it for a minimum of 3½–4 hours. At this stage the birds should be tender, but as a matter of fact old partridges

are often so incredibly tough that I have before now left them as long as 7 hours without them coming to the slightest harm.

To make the sauce, mix the flour and the rest of the milk (cold) to a smooth paste in a saucepan. Put it over very gentle heat and gradually add some of the hot liquid from the partridges, stirring all the time until the sauce is thick and smooth. To give the sauce an extra lift, a couple of tablespoons of brandy, Calvados or Armagnac could be added at this point. The sauce should not be too thick – just about the consistency of thick cream.

Discard any liquid remaining in the pot. Pour the sauce (through a strainer if by any chance it has turned lumpy) over the partridges and return the pot, covered, to the oven for at least another half hour. Serve with plain boiled potatoes and french beans.

This is simply the basic method of making the dish and small variations can be made by anyone with a bit of imagination.

With mushrooms or celery

250 g (½ lb) of mushrooms – sliced or quartered, cooked a minute or two in butter, well seasoned, and added to the sauce when it is thickened – make a big improvement. Alternatively, a couple of tablespoons of chopped celery or watercress or a seasoning of half a dozen crushed juniper berries.

Sunday Dispatch

, 1950s

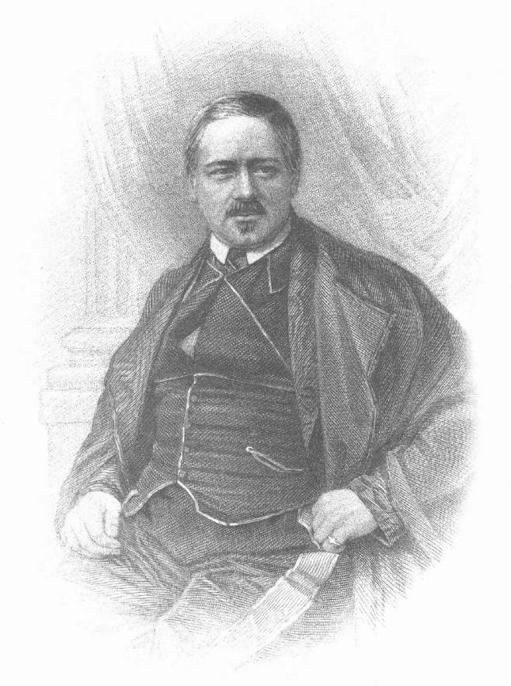

Alexis Soyer

Head chef in charge of a brigade of twelve undercooks in a Paris restaurant at the age of seventeen, Alexis Soyer came to England in 1831. In five years, working first under the aegis of his brother Philippe, chef to the Duke of Cambridge, subsequently in the kitchens of the Duke of Sutherland, the Marquess of Waterford, and for four years at Aston Hall, Oswestry, seat of a gentleman called Lloyd, he had made his mark among the London aristocracy and the landed gentry as a chef of great flair with a brilliant gift for organisation.

In 1837, still only twenty-five years old, Soyer was offered the post of chief cook at the recently constituted Reform Club. The

offer carried with it the opportunity to have his say in the lay-out and furnishing of the kitchens in the great new Club house planned to replace the old premises in Pall Mall. The architect was to be Charles Barry, and Soyer was to collaborate with him on the overall design of the kitchen quarters, the stoves, the equipment. For the ambitious, inventive, hyperactive young Frenchman it was the chance of a lifetime.

Soyer’s activities at the Reform are legendary. Within half a dozen years of the opening of the splendid new Club house in March 1841, he had made himself one of the three best known chefs in London. The Reform’s kitchens were the most talked of, most visited in the country. Cooking was done on a variety of fuels. There were coal, charcoal, and gas stoves – the latter a great innovation. The meat and game larder was fitted with slate dresser tops and lead-lined ice drawers, the temperature maintained at 35 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit. The fish was kept fresh on a large marble slab with three-inch high slate sides, and cooled by a constant stream of iced water. The table in the principal kitchen was made of elm, in an ingenious twelve-sided design. In the centre of the table was a cast-iron steam closet in which delicate entrées could be kept hot. On either side, the two columns supporting the kitchen ceiling passed through the table, and Soyer utilised them as supports for tin-lined copper condiment cases in which spices, salt, freshly chopped herbs, breadcrumbs and bottled fish sauces were kept. All seasonings were thus ready to hand for each cook working at the table without moving from his or her place. (Several of Soyer’s assistant cooks were young women.)

Today’s kitchen planners could do worse than make a study of Soyer’s own descriptions of his kitchen furnishings and of the illustrations supplied in his famous book

The Gastronomic Regenerator

. His gift for publicity, on the other hand, and his almost manic pursuit of it, would be difficult to emulate. It far out-classed that of any present-day Bocuse. What he might have done given television promotions, colour supplement treatments, public cookery demonstrations, chat show appearances, newspaper interviews, is scarcely to be contemplated. As an organiser of fund-raising events and famine relief he could have made Bob Geldof look like the village vicar. Even in mid nineteenth-century England, everything Soyer did was instant news. Whatever novelty he produced, from a new bottled sauce to a pair of poultry dissectors, from a six-inch portable table cooker to a gas-fired

apparatus for roasting a whole ox, every London newspaper, a good many provincial ones, and often a few Paris journals thrown in, had their say, and at length, about his latest doings. To

Punch

his whole career proved a god-sent gift.

When

The Gastronomic Regenerator

, a work of well over 700 pages, appeared in 1846,

The Times

compared the author’s labours to those of a Prime Minister or a Lord Chancellor, invoking for good measure the great names of Sir Robert Peel and the famously versatile Lord Brougham. Soyer’s book, it was revealed by

The Times

, had taken ten months to prepare, and during that time the great chef had furnished 25,000 dinners, 38 important banquets comprising 70,000 dishes, had besides provided daily for sixty Club servants, and received the visits of 15,000 strangers ‘all too eager to inspect the renowned altar of a great Apician temple’.

Impressive figures indeed. But

The Times

reviewer was quoting them from Soyer’s own foreword which he called

Description of the Composition of this Work

, in other words what would nowadays be the blurb printed on the dust-jacket. So the Thunderer’s tongue, it is to be feared, was ever so slightly in its cheek when it remarked that there was nothing to admire more in Soyer than his matchless modesty. Modesty, and matchless at that, isn’t the epithet that most immediately springs to mind in connection with Soyer. But reading the account of his life put together by his former secretaries, F. Volant and J. R. Warren, as a tribute following his death in 1858 and published in 1859, it becomes plain that, while modesty was not his strong suit – his achievements were after all something to boast about – he was at the same time an affectionate, endearing, much-loved, and rather touching character. I don’t think, in spite of his undoubted administrative genius and his marvellously inventive mind, that he ever quite grew up. Certainly he never grew out of his love of theatrical exploits, absurd practical jokes, awful puns, dressing up. His whirlwind enthusiasms and financial fecklessness were characteristics which alternately aroused the protective instincts and the exasperation of his friends.

The little volume, which his secretaries called

Memoirs of Alexis Soyer

, and in which their subject’s qualities and defects are very fairly assessed, must have been published in a small edition – surprisingly in view of Soyer’s contemporary fame – and is now a collector’s item of extreme rarity. The

Memoirs

make a valuable