It's a Don's Life (16 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

30 January 2008

I shall be rather sad if Britannia does indeed, as the Prime Minister plans, disappear from British coins. After all, it’s

part of the point of a modern coin design that it should include some hoary old symbol that is simultaneously easily recognisable

and also not fully comprehensible (or not comprehensible without a bit of research, anyway).

One of the Greek euros has the Rape of Europa on it: a frisky bull about to run off with – and worse – an innocent young maid.

(Imagine what the New Labour moral police would have done with that one.) And what on earth was that little bird on the old

farthing? Was it a wren or a robin? And why?

So Britannia fits the bill rather nicely. An appropriately antique goddess, invented by the Romans, as a symbol of their new

province, and used on British coins since the seventeenth century. If she goes, I don’t hold out much hope, long term, for

that nice bit of Virgil (‘

decus et tutamen’, ‘an ornament and a safeguard’ –

from

Aeneid

Book V) around the pound coin. I have a sneaking suspicion that Mr Brown isn’t much of a fan of Latin.

But while the traditionalists lament Britannia’s disappearance, they might like to reflect on her first appearance in Roman

art. As rape victim of the doddery old emperor Claudius.

She is first used on a coin under the emperor Hadrian in the second century ad, sitting on her usual rock. But her premiere,

so far as we know, was on a large building put up in the town of Aphrodisias (in modern Turkey, not all that far from Ephesus):

the so-called ‘Sebasteion’, a building complex of temple and porticoes, probably finished in the reign of the emperor Nero,

and dedicated to Aphrodite and the Roman emperors/gods (the ‘

sebastoi

’ in Greek).

It’s loaded with sculpture (in fact, Aphrodisias, which is still being excavated, is the place where some of the best ancient

sculpture has been discovered over the last few decades). There are personifications of the tribes and peoples of the Roman

empire, scenes from myth (from Leda and the Swan to Orestes at Delphi). And then there are more specifically Roman images.

One panel shows a heroically nude emperor Claudius shaking hands with his wife (and murderess, if you believe the stories),

Agrippina. Another has Agrippina crowning her son Nero with a laurel wreath.

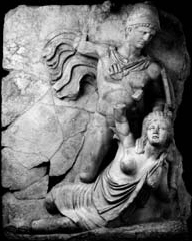

Yet another is the Britannia panel. Claudius, naked again apart from a bit of weaponry, is about to do something very nasty

to a sprawling Britannia, whom he’s pulling back by her flowing hair. She’s dressed in a tunic already falling away from her

breasts, and some little barbarian boots. We know it’s Claudius and Britannia because there’s an inscription going with it

that names them both.

As a commemoration of Claudius’ conquest of Britain, it’s about as classic a version of the erotics of military victory as

you could wish for. And it goes with another panel from the monument, which is an even more titillating picture of Nero having

his way with Armenia.

It’s a useful antidote to the confident, bellicose Britannia ruling the waves on British coins. She who is victor was once

victim; empires rise and fall; power comes and goes.

Of course, it’s exactly these ambivalences and mixed messages that make such old classical symbols so good for the coinage.

Pity we can’t celebrate that, rather than just chuck them out.

Comments

I’ve sometimes wondered who proposed ‘

decus et tutamen

’ for the pound coin. Was it some wit at the Bank of England with a good knowledge of the

Aeneid

? For the phrase refers to a breastplate that two attendants could hardly lift on their shoulders and carry away. Was the

idea that this chunky new pound coin would weigh down your pocket or make your purse too heavy to carry?

MICHAEL BULLEY

The question of ‘

decus et tutamen

’ on the pound coin is even more intriguing: the breastplate in question is awarded as

second

prize, and the narrator comments that the Trojan attendants can barely carry it between two of them – yet when it had belonged

to the Greek Demoleos, he could run about the battlefield at Troy in it. (

Aeneid

5.258ff.)

So – is the message that history is too great a burden for Britain and we will always be inferior to the heroic past and the

weight of Eastern and Mediterranean tradition we carry?

RICHARD

Surely ‘

decus et tutamen

’ on the Thatcher (brassy and thinks it’s a sovereign) was a motto used on coins at the time of the Restoration of Charles

II (who also had Britannia modelled on one of his lady friends). God knows the meaning of the twiddles on the Blair (gilded

on the edges, but base metal in the middle).

OLIVER NICHOLSON

Boudicca, Godiva, Matilda, Castlemaine, Emily Brontë, Eleanor Marx and Christine Keeler on future coins and notes, please!

XJY

It looks as if Britain could keep ‘

decus et tutamen

’ if it wanted to, when it finally takes the plunge and adopts the euro. I’ve just spread my loose change in front of me and

I see that, whereas the French 2 euro has no writing on the rim, the Netherlands one has. I also notice that, among these

30 or so coins, at least two nations are represented for each denomination. So that’s another good thing about the euro: it

puts internationalism into practice. I can go out tomorrow and buy things in the town with the solid metal currency of half

a dozen countries all mixed together.

Pax Romana

the second!

MICHAEL BULLEY

11 February 2008

This is my new project, which I’m soon going to be working on full time and full speed. But, as I was down to give a lecture

to a group of ‘lifelong learners’ on Saturday night (they were spending their weekend reading Latin at the University’s Continuing

Education Centre at Madingley Hall), I decided to give them a first taster.

So we spent an hour looking at Roman jokes. It’s a richer subject than you might imagine, though it’s a shame that some of

the best texts haven’t survived. Just think what you could have done with the 150 volumes of joke anthologies by one Melissus,

a contemporary of the emperor Augustus.

Still, I tried out some of those we do still have, curious to see how they went down.

The winner, I think, wasn’t exactly a joke, but a bit of Roman imperial sit-com. It’s a story about the bonkers emperor Elagabalus,

recounted in the hugely unreliable late imperial series of biographies known as the

Historia Augusta

. It still had them laughing on Saturday:

He had the custom of asking to dinner eight bald men, or else eight one-eyed men or eight men who suffered from gout, or eight

deaf men, or eight men of dark complexion, or eight tall men or eight fat men – his purpose being in the case of these last,

since they could not be accompanied on one couch, to call forth general laughter.

Elagabalus had a strong suit in practical jokes, and can be credited with the invention of a Roman version of the whoopee

cushion. But they had a dangerous side, too. He was the emperor (again according to the

Historia Augusta

) who showered his guests with so many rose petals they suffocated and died.

But as for jokes proper, the winner was an ancient version of a ‘nutty professor’ joke.

The source for this is a curious compilation of about 250 jokes in Greek, probably put together in the fifth or sixth century

ad, but including a good number of – even by then – very old chestnuts. It’s called

‘Philogelos

’ in Greek, or ‘Laughter Lover’ (and there’s a 1980s translation still available by Barry Baldwin).

The first hundred or so are all ‘nutty professor’ jokes (

scholastikos

in the Greek). Saturday’s favourite was this one:

‘That slave you sold me died,’ a man complained to a nutty professor.

‘Well, I swear by all the gods, he never did anything like that when I had him.’

Also raising quite a smile was one of the ‘Abderite’ jokes (that’s, I’m afraid, the ancient equivalent of the Irishman or

Belgian joke):

Seeing a eunuch chatting with a woman, an Abderite asked him if it was his wife.

The eunuch replied that people like him could not have wives.

‘Ah then, she must be your daughter.’

And finally, in third place, was one of a category not so familiar from our own repertoire – that is, jokes about blokes with

bad breath:

A man with bad breath went to the doctor and said, ‘Look, Doctor, my uvula is lower than it should be [a regular anxiety among

the ancients, ed.].’

‘Phew!’ gasped the doctor, as the man opened his mouth to show him. ‘It’s not your uvula that has gone down, it’s your arsehole

that has come up.’

No, don’t ask me to explain, if you didn’t get it.

Comments

What makes people laugh is very culturally and no doubt historically various. It is certainly not equivalent to finding something

funny. In central Africa, laughter expresses, or attempts to conceal embarrassment. For example, in a traffic accident, the

culprit may well laugh and the foreign victim is liable to misinterpret this as not caring, or even as an added insult ...

I was once at a performance of

Romeo and Juliet

in Lesotho. At the suicide of Romeo, the junior Basotho audience laughed uproariously, much to the obvious demoralisation

of the British performers.

PAUL POTTS

Eight fat men on a sofa: accompanied by whom?

I think people in Lesotho are not the only ones who laugh to conceal their embarrassment.

ANTHONY ALCOCK

13 February 2008

Valentine’s Day comes with a sense of relief for the middle-aged. At least you are not on tenterhooks about what might, or

might not, come in the mail. Truth to tell, apart from welcome tokens of affection from the husband, I don’t think I have

ever received a Valentine – of the traditional, unexpected, ‘wonder who it is’ sort.

Nor for that matter have I ever sent one, so far as I can remember. Except years ago as a joke to a senior colleague, who

was instantly convinced that it was from someone else. The less said about this the better.

None of which stops me being curious about the Roman history of all this. In fact, for all of you wondering if there was ever

a real Saint Valentinus, the good news is that there was not just one, but three.

The bad news is that we know almost nothing reliable about him/them. Earnest and detailed articles about his true history

have, I am afraid, fallen for some very unreliable parts of Valentine’s myth.

The ‘facts’ are these.

There are three possible Valentines for our purposes (leaving out the tens of other saints also known by that name – a common

one in the Roman empire):

A stray North African

A bishop of Terni (in Italy)

A priest in Rome

So far Wiki is reliable, but then – though it’s actually better than most accounts – it gets a bit dodgier.

The stray North African doesn’t actually get you very far. The second two were both supposed to have been martyred on 14 February,

though not necessarily in the same year, and may indeed have been the same person (if they ever existed, that is).

We don’t have any contemporary accounts of the martyrdom of this pair (?one). But there is a sixth- or seventh-century version

which gives them their separate stories. Here the Roman Valentine is said to have been martyred under the emperor Claudius

– Claudius Gothicus (268–70). Only trouble is that Claudius Gothicus was a tolerator of Christians, and was hardly in Rome

to persecute Christians anyway. The other Valentine, of Terni, may have been martyred in the 270s (no firm date is given),

but his story and miracles are not unlike his Roman namesake – more reason for wondering if they are the same. No sign, in

either case, of being a patron saint of lovers.

According to the most rigorous modern scholar of our saint (Jack B. Oruch, who wrote a famous article on the subject in

Speculum

for 1981), that particular element was not actually invented until Chaucer – who was looking for a lovers’ saint to mark the

start of spring. (February, start of spring before global warming? Well, it was helped, apparently, by the calendar being

out of synch with the seasons in the fourteenth century.)

But there is another ingenious twist, which appeals to me – although it is, almost certainly, quite wrong. One smart scholar

of the eighteenth century shrewdly asked what the pagan Romans would have been doing on 14 February. Answer: in Rome itself,

they were in the middle of the weird festival of the Lupercalia (in which naked young men raced round the city, beating with

thongs any woman lucky enough to get in their way). One thing we know is that in the late fifth century ad Pope Gelasius was

angry to find his flock still enjoying this pagan festival, when they should have been being good Christians. So what does

he do? He invents St Valentine’s day, to give his wayward people a fun, but Christian, festival to replace the Lupercalia.

Lovely idea, but not a shred of evidence.

Comments

I’m not sure which of the many Valentines it is, but what are claimed to be the bones of St Valentine are at present in the

Carmelite church in Whitefriars Street, Dublin. An Irish Carmelite preacher so impressed Pope Gregory XVI by his preaching

when he visited Rome in 1836 that he was given a casket containing the saint’s bones when he left to return to Ireland. Accompanying

them was a papal certificate of authenticity. However, in the current Roman calendar February 14th is the feast of Sts Cyril

and Methodius, apostles to the Slavs and supposed originators of the Cyrillic alphabet. Perhaps St Valentine has been silently

disavowed.

DAVID KIRWAN

I would like to think that Valentine was the gnostic thinker of the 2nd cent. AD responsible for the Sophia myth recounted

in a couple of Nag Hammadi texts. Sophia, an outer aeon, ‘fell’ and was responsible for the creation of the material (

hylic

) world, but was ultimately restored to her former status by her

syzygy

, Christ, who gave the

hylic

world a fighting chance of survival. Basically, a boy meets girl story.

ANTHONY ALCOCK

I am shocked on reading David Kirwan’s post that the Roman calendar still has a feast of St Cyril. Wasn’t he the bishop of

Alexandria who had Hypatia murdered so tragically?

ARINDAM BANDYOPADHAYA

Cyril seems to have been a fairly unscrupulous ecclesiastical politician, who was very probably deeply engaged in a power

struggle with the Prefect of the city, Orestes. Hypatia, who seems to have been friendly with Orestes, may have got in the

way. Kingsley’s account may not be so far from the truth, assuming of course that there is such a thing. Socrates, in his

Church History

, accuses Cyril of plundering the Novatian churches and expelling the Jews from Alexandria. Cyril certainly seems to have

had a fairly shrewd idea of how to control the hairy hooligans who inhabited the desert in various parts of Egypt.

ANTHONY ALCOCK