It's a Don's Life (19 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

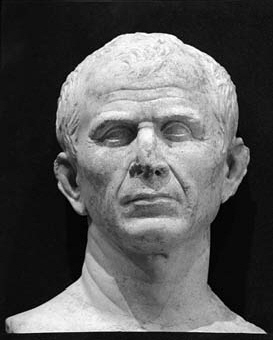

The face of Julius Caesar? Come off it!

14 May 2008

What do you do if you are an archaeologist and you find a nice Roman portrait bust in the bottom of a river?

The answer is simple. You go through every book of Roman portraits and coins until you find some famous figure in Roman history

who looks vaguely likely your man. It is laborious and time-consuming. But the principles are simple – it’s like a game of

snap.

Why bother? Because almost every newspaper in the Western world will be interested in your find if you say confidently that

it is Cleopatra or Nero or Julius Caesar (and even more interested if you say that this is the earliest statue or the only

one really taken from life – which is also a useful cover-up for the fact that your statue doesn’t look quite like all the

others supposed to represent the famous figure).

However beautiful or important your find, no newspaper will be searching you out if you have only found Marcus Cornelius Nonentito.

There’s a long tradition to this game. Heinrich Schliemann tried to convince the world that he had gazed upon the face of

Agamemnon. Almost every local archaeological society in England was certain that the tiny little Roman villa they were digging

up was actually the governor’s residence – and they labelled the plans accordingly, ‘Governor’s wife’s bedroom’ and so on.

Now we have the story of the only surviving statue of Julius Caesar to be sculpted from life dragged out of the river at Arles.

Right?

This sculpture is, I should say, a very nice piece of work – and looks remarkably good for something that has been at the

bottom of the Rhône for a couple of thousand years. There is, I suppose, a remote possibility that it does represent Julius

Caesar, but no particular reason at all to think that it does – still less to think that it was done from life.

The game of art-historical snap is a risky business, and honestly you could find hundreds of Romans who, with the eye of faith,

look pretty much like this. Besides – despite all you get told about the style of the portrait pinning it down to a few years

– this style of portraiture lasted for centuries at Rome. There is nothing at all to suggest that it came from 49–46 BC.

The desperate archaeologist in this case has, of course, found a nice reason for imagining how a made-from-life portrait of

Julius Caesar might have ended up at the bottom of the Rhône. It was chucked there after Caesar had been assassinated and

so had fallen from favour.

Has he forgotten that that was the very moment when Caesar was turned into a god?

Well, he might respond, the burghers of southern France took a dim view of such flummery. OK, so why did they throw that nice

statue of Neptune, apparently found in the same haul, into the river too?

I’m afraid it’s ‘start again’ time on the explanations for this one.

Comments

Plenty more suggestions for the identification of the mystery man were made by commentators. There were votes for, amongst

others: Mel Gibson, Augustus, Mark Antony, Sid James, Tiberius Claudius Nero, George Bush, Claudius ... and some longer comments.

How do we even know that it wasn’t thrown into the river ‘yesterday’? The handling of the nasal-labial folds doesn’t look

very Roman to me.

EILEEN

As you say, it’s not a new phenomenon and I can’t help thinking ‘I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon’ was a rather good

line. Back in the 18th century, Alexander Pope, in his ‘Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot’ was satirising wealthy collectors typified

by Bufo, in whose library ‘a true Pindar stood without a head’.

KATH

It’s the closeness and beadiness of his eyes that make him resemble George Bush, features he shares with the Tivoli General.

I disagree with the suggestion that it was meant for insertion into a statue-body. There is too much shoulder and chest for

that. Insertable heads have only a neck.

What exactly is the problem with the handling of the nasolabial lines? They look to me like many other republican examples.

Perhaps their doubling here is unusual, but an unusual stylistic feature is, as we all know, not a reason to assume a forgery.

LIZ MARLOWE

I think that what can happen with these ‘

plus éminents spécialistes

’ is that Prof. X has a theory, as it might be the identification of the subject of a portrait, and bounces up to another

professor, full of excitement, and runs it past him. If Prof. Y believes that it is complete hogwash he will say, ‘Well, of

course you might be right, but I wouldn’t like to bet on it; have you considered factors a, b and c?’ If, as might be the

case here, Prof. Y believes that the theory is dubious, while not complete hogwash, he will probably say, ‘What a brilliant

idea! Quite probably you are right, though I suppose that a sceptic might want to be convinced on point a’, or something like

that.

Why? Well, Prof. X is full of the joys of spring and the exhilaration of discovery, and Prof. Y doesn’t want to rain on his

parade. And he knows that he hasn’t spent as much time thinking about it as Prof. X has, and is likely to be disinclined to

disagree with somebody who has done the donkey work when he hasn’t.

I think the same thing happens with papyri. Prof. A thinks he can read something, and asks Prof. B for a second opinion. Prof.

B has a quick look, and says, ‘I think you may well be right.’ When Prof. A advocates his theory to somebody else at the pub,

he says that Prof. B agreed with him: but Prof. B didn’t really agree, he just made encouraging noises ...

If you are an eminent specialist and not being named, you are not putting your own reputation on the line, and may well prefer

to be polite and encouraging. What counts is whether somebody agrees with you in print with their name at the bottom of the

article ...

RICHARD

Richard’s eirenic explanation of professorial psychology reminds me of a friend’s explanation of the notorious (and often

misquoted) observation of Bishop Jenkins of Durham that the Resurrection was ‘not just a conjuring trick with old bones’.

The bishop was previously a professor; ‘the trouble is’, said my friend, ‘he thinks that the Gentlemen of the Press are bright

undergraduates who need stimulating’.

OLIVER NICHOLSON

After reading this piece, I tore open the plastic wrapping from today’s just-delivered

Le Monde

. The subheading says: ‘“

C’est le seul buste connu de César réalisé de son vivant,

”

annonce Luc Long.

’ What worries me about M. Long is that when someone asks him at a party what he does for a living, he has to say, ‘I am the

principal heritage curator at the department of subaquatic and undersea research of the Ministry of Culture.’

MICHAEL BULLEY

I recently received the following letter from my old friend Hercule Poirot and in view of its importance in this matter I

feel it should be made public.

My Dear Friend,

I ‘av been reading the enormous number of comments concerning this discovery and am surprised that no one – no one –including

the esteemed lady professor, has made, what to me is the most instantly obvious observation concerning it.

I ask you,

mesdames et messieurs

, to look carefully at this portrait bust and ask yourselves one simple question.

If I had a face like that, would I want it immortalised in stone for all time? Would my wife–colleagues–friends, on passing

it each time they came to dinner, look on it reverently and say in hushed tones, ‘What a great–noble–handsome–sensitive man

your husband–senator etc. was’?

The answer

mes amis

is clearly, No!

Only if – only if –

mes amis

, the person depicted was so immensely, so enormously important that they agreed – indeed, that it was demanded of them –

that they must be portrayed for all time for history as similarly as your Oliver Cromwell indicated, warts and naso-labials

and all ...

This can therefore only be a bust of a very, very, very great man. And I am sure that my friends in the various French archaeology

departments with their computerised facio-cranial measurements etc., will have confirmed that this is indeed Julius Caesar.

Some people have protested that no soldier would follow a man with such a face, but

messieurs

, the extreme depth of those naso-labials indicates a man of great endurance and ruthlessness, as Caesar was known to be.

Finally, may I suggest to the commenters, perhaps, a little less all-night raving and a little more use of those little grey

cells.

Your Friend Hercule Poirot

LORD TRUTH

22 May 2008

I am on sabbatical leave and taking off to give a lecture in Chicago while our students hone their skills by translating Barack

Obama and Milan Kundera into Latin and Greek. I kid you not. In our day it was Macaulay or Churchill if you were lucky (he

was easier). But I guess that the effect of the Latin is to make Obama sound much like Macaulay anyway.

It’s hard to live through a summer term here without a little nagging doubt about what exactly we are putting them through

the exam routine FOR. It’s nowhere near as bad as the school examining business which is currently getting itself tied up

in knots about accuracy and objectivity.

Their double bind is quite simple. The more kids you examine, the more examiners you need. In the bad old days, when we had

only a small number of kids doing A level, then we could afford to have wise and experienced examiners evaluating exam answers

about the relative merits of Gladstone and Disraeli – with confidence.

The more kids take the exams, the harder it is to find enough examiners (the pay is lousy), the less experienced and qualified

they will be overall (I don’t mean individuals), and the more we need to keep a careful eye on what exactly they are getting

up to. The totally safe way out is multiple choice. Even a computer can mark that. If not multiple choice, then every question

has to come with a set of acceptable answers handed out to each examiner. This lets you put even trainee teachers into bat

– all they have to do is match up the candidate’s answer with their checklist.

The only trouble is that it stamps on imagination, independence and eccentricity, or on any poor child who has the nerve to

mention a point not on the list. ‘Not on the list’ = ‘no marks’. In the bad old days we relied on the wise and experienced

to distinguish the eccentric and silly from the eccentric and brilliant. It’s an inexact science, sometimes they made mistakes

or weren’t so wise and experienced after all, but we trusted them.

We haven’t figured out how to have mass examining without a mechanistic approach to learning which in the end equals dumbing

down.

Cambridge students are lucky by comparison.

We all accept that exams don’t test every skill, and I suspect that there is a blokeish element to success in them (whether

in women or men). So increasingly we use ‘alternative methods of assessment’ too, dissertations or portfolios of essays. But

exams do test some skills we value. I, for one, am not knocking the acquisition of knowledge, useful memory, the ability to

deploy learnt knowledge, to answer the question and to make a good argument. And our exams aren’t bad at testing those things

– as fairly as you could possibly hope.

Every exam script is marked anonymously. In the old days, you used to recognise the handwriting of the students you had taught,

however ‘anonymous’ it was. But now you have most likely never seen your students’ handwriting, so that problem has gone.

Each script is also marked by two people – first independently, then in consultation. I remember that, when I was a student,

we used to worry hugely about the ideological differences between the two examiners. Would the trendy Professor X mark you

down for what the philological Professor Y would value? In my experience, both Professor X and Y are looking for students

to answer well, under any ideological banner.

When examiners differ it is more often than not because one examiner has ‘read’ or ‘understood’ what the student was saying

in different ways. Sometimes, honestly, when you talk to your fellow examiner, you see that you have just missed the student’s

point. Or the other examiner sees that he or she has given the kid too much benefit of the doubt. If you still don’t agree,

it can all be read by the external examiner. Yes, it’s a time-consuming process.

OK, I can see that this tendency for examiners to agree might simply reflect an unspoken, unreflective collusion by a conservative

academic establishment about what counts as ‘good answers’. But I doubt it, honestly.

If any students are reading this, let me just say: stop worrying about all those arcane things that could go wrong – more

marks are lost by NOT ANSWERING THE QUESTION than by any other failing at all.

Comments

Don’t remind me about answering the question! I well remember an assignment I did some years ago. My tutor’s comments started

with ‘This would have been an excellent essay if the question had been “Why Did the Romans Get Married?”’

JACKIE

Grading to a marking scheme in A levels was one of the worst experiences of my life: if your answer isn’t there, nor are the

marks. We were also instructed to accept certain ‘wrong’ answers, because a recommended text book contained errors.

ARMCHAIR PROFESSOR

Jackie – why did the Romans get married?

RICHARD

Richard – where would you like to start?! It was a few years ago, and I can’t find the assignment (I think it’s in the loft!)

but I seem to remember the transfer of property figured quite a lot, and legitimate children. Political connections figured

highly as well. And didn’t Augustus bring in laws about people having to marry in an attempt to increase the population, and

clean up morals? Or at least offering inducements to those that did. Certainly the last thing to be considered was female

choices, though having three (I think) children gave the mother a degree of freedom which might have been tempting!

JACKIE

Exams are great. I always did well at most of the written ones. And my daughter has inherited the flair but also has a killer

instinct for arguing/bullying teachers into submission that she gets from her mum. Since ability in the subject has almost

nothing to do with it, and a good short-term memory and a bit of flash has everything, I think exams are perfect for turning

out game-show producers and/or presenters.

XJY

They also teach one of the most valuable lessons one can take into life: Focus and ATFQ.

STEVE THE NEIGHBOUR