It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation (20 page)

Read It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation Online

Authors: M.K. Asante Jr

Most of the African-Americans in prison today are political prisoners. The War on Drugs and mandatory sentencing, responsible for the explosion of incarceration we see today, takes the power of release from parole authorities and discretion from judges and allows for legislatures to set sentencing policies. Franklin Zimring, a criminologist at the University of California, Berkeley, says, “Punishment became a political decision.” Even conservative Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist acknowledges that sentencing is politically motivated, remarking that “mandatory minimums are frequently the result of floor amendments to demonstrate emphatically that legislators want to get tough on crime.”

The result of this politicization leads to an increasing number of people, organizations, and institutions that benefit significantly from the policies that not only mass-police, but mass-incarcerate and keep people in prison for lengthy amounts of time.

The prison industrial complex, in subtle ways and in overt ways, is political. Consider for example that Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), the largest private prison operator, was started by a major investment from Honey Alexander, the wife of then Tennessee governor Lamar Alexander, and Ned McWherter, then speaker of the Tennessee house, and later governor.

“CCA has been one of the most successful companies on Wall Street,” says Harmon Wray of Restorative Justice. CCA now builds prisons based on speculation. This intimacy between prison and politics means that there are many with great financial stakes in the current structure—interest groups that have incentives to ensure their prisons can stay full. On top of that, you have other companies that reap hundreds of millions of dollars annually by providing health care, phones, food, and other services to the new prisons. Many small

white rural towns depend on the influx of imprisoned Black urbanites to survive economically. And private prison companies, including CCA, contribute huge sums of money to the American Legislative Exchange Council, a policy group that has helped draft tougher sentencing laws, and the California prison guards union doles out millions every election to tough-on-crime candidates—or, put another way, candidates who will ensure their livelihoods at the expense of entire communities.

Political elements not only determine who goes in, but who comes back. Former prison inmates are punished even after they have served time. “Laws deny welfare payments, veterans benefits and food stamps to anyone in detention for more than 60 days,” writes Berkeley sociologist Loïc Wacquant. “The Work Opportunity and Personal Responsibility Act of 1996 further banishes most ex-convicts from Medicaid, public housing, Section 8 vouchers and related forms of assistance.” Bill Clinton, in particular, “proudly launched ‘unprecedented federal, state, and local cooperation as well as new, innovative incentive programs’… to weed out any inmate who still received benefits,” writes Wacquant. In addition, convicted felons are further disenfranchised because they cannot vote or participate in political elections. It should be noted that the only states that allow prisoners convicted of felonies to vote after their release are Maine, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island—states with very small African-American populations.

While recognizing

the institutional racism that creates and maintains these laws, the new generation does not simply treat this as a Black issue. Rather, they see it “as a challenge for all of us, for humanity,” Ahmed Artis tells me as he relaxes on a charter bus that motors him back home to Los Angeles after a monumental day in Jena, Louisiana. “This is something that affects all of us, and you could feel that

today; Black people, Latino, white, Asian, Pacific Islander, everybody was united.”

James Baldwin once reminded us that “We live in an age in which silence is not only criminal but suicidal… for if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.” And indeed they already have. Alisa Solomon writes in

The Village Voice

that “the only incarcerated populations sustaining reliable growth now are INS detainees and federal prisoners, many of them noncitizens.” Starting in 2001, the Federal Bureau of Prisons began directing prison contractors to “build prisons that meet a new category called Criminal Alien Requirements.” According to the Justice Department, between 1995 and 2003, convictions for immigration offenses rose by 394 percent. Additionally, between 1980 and 2005, the number of women in state and federal prisons jumped by 873 percent—from 12,300 to 107,500.

Poverty has always been the defining feature of who is imprisoned in the richest country on earth. Today is no exception. As of 2005, approximately 37 percent of women and 28 percent of men in prison

had monthly incomes of less than six hundred dollars prior to their arrest. The law—a political institution in itself—provides the framework for the war of social control against oppressed people, working classes, and noncompliant women. The vast majority of prisoners are not imprisoned because they are “criminals,” but rather because they have been criminalized. Although challenging, this great dilemma represents, for the post-hip-hop generation, a way to unify. What is increasingly clear is that the racialized and politicized prison industrial complex is one of the great moral and political challenges of our time. Indeed, it is our cultural assignment.

Assata Shakur

was sentenced to spend the rest of her life rotting in a super-maximum-security prison. However, her spirit and the spirit of her community wouldn’t allow that to happen. “Love is the acid that eats away bars,” she reflects on her great escape, adding, “I have been

locked by the lawless. Handcuffed by the haters. Gagged by the greedy. And, if I know anything at all, it’s that a wall is just a wall and nothing more at all. It can be broken down.”

Following the marches in Jena, young people began the process of breaking down those walls. Not satisfied with a single day of protests, students, once again taking the lead, organized a post-Jena meeting where they not only explored the problems that create and foster Jenas around the county, but identified solutions as well. They came up with a plan to put pressure on local, state, and national officials to end mandatory minimum sentencing and revise federal sentencing guidelines. They also recognized that the current War on Drugs spends the bulk of its resources locking up users. A year of treatment costs much less than a year of incarceration and it would allow a person to work and support a family. Pushing for drug rehabilitation, thus changing the approach to the War on Drugs, was a vital part of the discussion. Also, they proposed to radically change the structure of probation. Two-thirds of people on probation are rearrested, mostly on technical violations. Probation policies should provide resources to help people stay out of jail, not be a force to put them back in. In Baltimore, where they’ve seen unemployment rates soar as ex-offenders are released, they knew it was essential to put an end to the legal discrimination of people who have served time. We can do this by restoring full access to public housing, welfare, food stamps, student financial aid, driver’s licenses, state-licensed professions, and voting rights.

It is important for the new generation to understand that there is nothing inherently unique about the situation in Jena. Around the country, in each state, one can find an abundance of equally unjust cases involving young African-Americans. Jena is important; however, it is only because young people have made it important. It is news because young people have made it news. This new generation, spurred by innovative

grassroots organizations like Color of Change, which utilize “the organizing power of the internet” to call to action, has shone a spotlight on Jena—one whose gleam has been effective both in raising national awareness and in amending the case itself.

“The walls

, the bars, the guns and the guards can never hold down the idea of the people,” Huey P. Newton, cofounder of the Black Panthers, once said. The idea of the people, today, is the same as it was yesterday. The idea is, has always been, freedom. Simple.

George Jackson, one of the most well-known political prisoners, who published a collection of letters entitled

Soledad Brother

while incarcerated at Soledad Prison, remembered that,

Down here we hear relaxed, matter-of-fact conversations centering around how best to kill all the nation’s niggers and in what order. It’s not the fact that they consider killing me that upsets… The upsetting thing is that they never take into consideration the fact that I am going to resist

.

The only sane thing we can do, given the situation we all find ourselves in today, is resist. According to Amnesty International’s definition, the vast majority of African-Americans imprisoned today are political prisoners. If our government refuses to recognize this fact, then we must take it to the international level. Following World War II, the Nuremberg Trials, and in fact the world, agreed that:

Individuals have international duties which transcend the national obligations of obedience. Therefore [individual citizens] have the duty to violate domestic laws to prevent crimes against peace and humanity from occurring

.

Contrary to popular belief, the most terrible occurrences (slavery, war, genocide) occur only when there is no resistance; when we, in essence, allow them to. What is happening today is only happening because we are allowing it to. The time has never been more just, the hour never more right to act, than now.

Regardless of the outcome in Jena, it is imperative that we claim no easy victories. The injustice in Jena must be looked upon as a symbol of the problem, but not the problem. If this generation is to truly be successful in making America live up to its promise of freedom and equality, we cannot simply move from here to the next Jena. Instead we must use this momentum to educate each other about the systemic issues that allow Jenas to happen and then do what each generation is called to do: change the world.

If you try to tell the people in most Negro communities

that the police are their friends, they just laugh at you.—

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR

.

Fuck the police.

—

TRADITIONAL SAYING

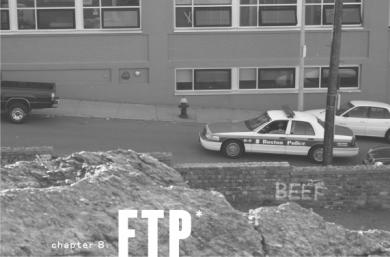

SAMO was the graffiti

name artist and pop icon Jean-Michel Basquiat spray-painted on lower Manhattan walls in the early eighties. When asked what his tag meant, he’d sigh, “same ol’ shit.” Regardless of the time period or generation, from the iron shackles of bondage to the platinum ones of today, African-Americans’ relationship to the police has been nothing short of the SAMO—a consistent, involuntary arrangement of fear, hostility, violence, and overall distrust. It is this relationship, built upon centuries of unspeakable acts, that gives a grassroots campaign like “stop snitchin’,” a national code of silence

among young Blacks, its proper context. The questions we must concern ourselves with now, however, revolve around our ability to trek beyond the usual castigations and FTP rhetoric, and instead, employ our collective imaginations to achieving something new, if for no other reason than because our very lives depend on doing so. While the hip-hop generation has been steady at voicing our frustration with the current system of policing, it has failed in its ability to imagine anything that might supplant it. If the next generation—us—is to be successful, we must, as one young man told me after he’d witnessed his friend assaulted by the police, “stop talking about it and be about it.” Or, as it goes, be subject to the SAMO.