It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation (24 page)

Read It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation Online

Authors: M.K. Asante Jr

It’s important for the new generation to keep in the forefront of our minds that all struggles against oppression and exploitation are connected. We cannot take a position of spectator or watch from the sidelines. Imagine yourself stumbling upon an innocent person being brutally beaten. Would you try to stop the beating? Run? Call for help? Or be neutral in the matter? In this situation, which is happening now, anything less than full commitment to the victim is aiding the oppressor. We must listen to Elie Wiesel, the Romanian Holocaust

survivor, when he demands, “Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

Take a look around and be for or against

but you can’t do shit if you ridin’ the fence

.—

THE COUP, “RIDE THE FENCE

,”

PARTY MUSIC

Oppressed peoples of the world: I have seen your face in the mirror and so have my brothers and sisters. For we know, as James Baldwin told us, “We must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is—and render impassable with our bodies the corridor to the gas chamber. For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.”

To you, we shout:

El pueblo unido jamás será vencido.

El pueblo unido jamás será vencido

.

As long as someone controls your history,

the truth shall remain just a mystery.—

BEN HARPER

When you control a man’s thinking you do not

have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell

him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his “proper

place” and will stay in it. You do not need to send him to

the back door, he will cut one for his special benefit.

His education makes it necessary.—

CARTER G. WOODSON

The only thing about the future we don’t already

know is the history we haven’t already read.—

HARRY S

.

TRUMAN

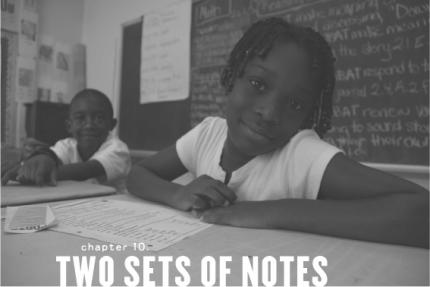

King Drew Magnet High School

, located in the heart of Compton, was known as one of the better schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Founded in 1982 to address the underrepresentation of Blacks and Latinos in the health care professions, King Drew had

a reputation for providing students from the Watts community with hands-on experience in the fields of science and medicine. Given King Drew’s brief yet propitious history, I was more than happy to accept an invitation to speak to the entire school about my work as an artivist. A series of dramatic, disturbing events, however, would drastically change our collective agendas.

Then they tellin y’all lies on the news, the white people

smiling like everythin’ cool

But

I

know people that died in that pool

, I

know people

that died in them schools

.—

LIL’ WAYNE, “GEORGIA BUSH

,”

DJ DRAMA

The voyeuristic images of downtrodden, displaced, and disillusioned Black folks in New Orleans coupled with impromptu comments like Kanye West’s “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people” were, albeit temporarily, news items. So much so that I received a call the morning I was scheduled to speak at King Drew from a reporter at BET.

“I’m working on a story about the Katrina aftermath and wanted to ask you a few questions,” the reporter queried in a bare baritone.

Time itself is neutral and can either be used in a constructive or destructive manner. I decided to use time as constructively as possible by agreeing to be interviewed about two hours before my talk at King Drew High School. We’d meet at 5th Street Dick’s Coffeehouse, a Black-owned community staple just off Crenshaw Boulevard.

Because of the clogged commuter chaos that is L.A. traffic, I arrived for the interview about forty-five minutes late. This meant, unfortunately, I could only afford to rap for a

minute

.

“I’m speaking at a high school in about an hour,” I told the genial reporter as I joined him at a table that was pressed against a colorful wall that held a sun-tinged poster, cornered in a wiry black frame, of a

preaching Malcolm X. Below his fiery figure, the searing adage

Only a fool would let an enemy educate his children

rested like the limestone base of a Nubian step pyramid.

“No problem,” he replied hastily before diving in: “Okay. What, if anything, has the whole Katrina

*

aftermath showed you?”

“What has it showed me?” I repeated as I thought about a New Orleans woman who exclaimed that she was “one sunrise from being consumed by flies and maggots.”

“It showed us, in gross reality, that the U.S. government

still

doesn’t value Black life at all and, in fact, has been one of the greatest threats to Black life. It showed us that what our ancestors—Truth and Tubman, DuBois and Douglass, Huey and Hampton—fought and died for: freedom and human rights, are things we

still

don’t have today. And, perhaps most of all, it showed us why we cannot fully depend on the U.S. government for our well-being. And still more, why we must look after each other. We are a great and noble people and the price of our greatness and nobility is that we have to be responsible for each other, because clearly we can’t depend on them.”

“Who is them?” he challenged.

“Them

is the individuals and institutions that can fight a war abroad, spending billions daily, but can’t get my people food and water after six days; the individuals and institutions that degrade and dehumanize Black life; the individuals and institutions that locked my people in the Superdome; that shot Black boys on bridges; that dubbed survival ‘looting’; that profit from our loss. They know who they are and so do we.” And with that, I was out.

These blocks are a jungle, and the police are the beast!

The school system is tall trees, designed

to keep the fruit out of reach

.—

EM SEA WATER, “BALTIMORE

,”

L.I.V.E: THE LOVE LIFE

King Drew High School, sprawled on the corner of 120th and Compton Boulevard, was a modern mix of terra-cotta bricks, glass slits, alabaster cylinders, and tiny prisonlike windows. A sign boasted to passersby:

KING/DREW MAGNET HIGH SCHOOL

OF MEDICINE AND SCIENCE

Both the American and the California Republic flags trembled on stiff poles high above the school’s capstone. I wondered if the sizable Mexican student population knew that the California Republic flag (or bear flag) was designed by American settlers on a piece of fresh southern cotton when they were in a revolt against Mexico. That, in essence, this blazing flag, hoisted high above their heads, was a symbol of Mexican defeat.

Guess it’s the same as the American flag for me, though

, I reasoned.

Jews don’t salute the fuckin’ swastika

But niggaz pledge allegiance to the flag that accosted ya

.—

RAS KASS, “NATURED OF THE THREAT

,”

SOUL ON ICE

I was a few minutes early and decided to take a seat in the hallway and get my notes together. Moments later, I was joined by Lisa, an eleventh-grader whose skin was as dark and smooth as the glossy shells of Spanish chestnuts. She sat across from me and I noticed that her eyes, masked in blue contacts, wouldn’t lift high enough to meet mine so I spoke first:

“ ’Sup.”

Her face, one half hidden behind tracks of strawberry-blond weave, rose.

“Hi,” she whispered, her eyes wandering before finally landing on the book in my hand.

“You reading that?” she chased.

“Yeah,” I said, glancing at the cover—

The Wretched of the Earth—

and offering her a look at the book. “Here, wanna check it out.” She didn’t budge, then finally—

“I don’t read nothin’.”

“Nothin’?” I asked to be sure.

“Nope, nothin’, ‘less it’s for school,” she confirmed.

“That’s not cool, you know,” I said, not really knowing what to say. “See, this book I’m reading right here is interesting because it breaks down a lot of information—information we should know as African-Americans,” I said, to which she sprung a chuckle.

“What?” I questioned. “What’s funny?”

“African?” she quizzed.

“Yeah. African,” I said with a curious authority.

“I ain’t African,” she swore.

“Where are your ancestors from, then?” I pushed back.

“I

dunno

, Europe or somewhere,” she said, straight-faced.

I scanned her face, searching for signs she was just joking.

She wasn’t.

“African refers to our ethnic origin, American refers to our nationality, that’s why I called you ‘African-American.’”

“I told you I ain’t African,” she snapped.

I breathed as deeply as my lungs would allow.

“Marcus Garvey said people who don’t know their history are like trees without roots.”

“Who?”

“Marcus Garvey was a very influential and important Black man.”

“Umph

. I hate Black people,” she said spitefully.

“Hate?” I said, shocked.

“Yeah, ’cause they ignorant. Not like white people—they sophisticated,” she explained to me.

As I looked into the windows of Lisa’s soul, I saw the eyes of Pecola Breedlove, the main character in Toni Morrison’s 1970 novel

The Bluest Eye. The Bluest Eye

, Morrison’s first novel, is set in her hometown of Lorain, Ohio, and focuses on Pecola’s hostile childhood. What’s painfully clear throughout the novel, as we watch little Pecola fall in love with the ivory image of Shirley Temple and hear her nightly prayers to God for blue eyes, is that Pecola’s world has been molded by the narrow and unattainable standards of white American culture.

Each night Pecola prayed for blue eyes. In her eleven years, no one had ever noticed Pecola. But with blue eyes, she thought, everything would be different. She would be so pretty that her parents would stop fighting. Her father would stop drinking. Her brother would stop running away. If only she could be beautiful. If only people would look at her

.

Morrison’s ideas were undoubtedly influenced by Malcolm X who warned us that “black people will never value themselves as long as they subscribe to a standard of valuation that devalues them.” Afrocentrists followed this up with the idea that Africans should view the world through their own eyes and certainly not through the spectacles of people who view them as inferior.

I thought of the BET interview I’d just done and I realized that Lisa, a victim of the American school system, was no different than the victims of Katrina. The government had failed her, just as it had failed the people of New Orleans (before and after the storm hit). We must ask ourselves: If we can’t depend on the local, state, or federal governments to provide water and food to the Black victims of Katrina, can we—should we—depend on

them

to fully educate us?

The answer, as I thought back on my experiences in the public, private, and alternative school systems in Philadelphia, in college and graduate school, and now as a professor, is absolutely not—especially if one wishes to come out alive.

If no historian, as Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz points out, “would accept accounts of Nazi officials as to what happened in Nazi Germany because those accounts were written to justify that regime,” why in the world are Black children, Latino children, Asian children being taught their history from accounts written by those who enslaved them, committed acts of genocide against them, tortured them, and put them in interment camps?

And it is in this question that we begin to realize the power of education, the power of how and why we learn what we learned. We begin to understand why David Walker, who was born to an enslaved African, quizzed, “For colored people to acquire learning in this country, makes tyrants quake and tremble on their sandy foundation. Why, what is the matter? Why, they know that their infernal deeds of

cruelty will be known to the world.” And why Elijah Muhammad, more than a century later, responded, “The slave master will not teach you knowledge of self, as there would not be a master-slave relationship any longer.” In this, we also see that we cannot leave the educational process up to those whose purposes and objectives are different from ours and expect us to walk in the footsteps of our ancestors. How can we follow the examples of Ella Baker or Robert Williams if we don’t learn about them?