Jacky Daydream (13 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

I was sad to miss out on my imaginary conversations on the way to school, but it was companionable having Cherry to walk back home with. We’d take our time. We’d run up the old air-raid shelter in Park Road and slide right down. We’d climb little trees on the bombsite and walk along the planks crossing the trenches where new houses were being built. We’d visit the sweetshop

on

the way home and buy sherbet fountains and gob stoppers and my favourite flying saucers, cheap pastel papery sweets that exploded in your mouth into sharp lemony powder.

I’d occasionally go home with Cherry. Her mother was sometimes out, as she worked as a hospital almoner. They had a big piano in the living room. The whole family was musical. Cherry played the recorder and the violin. Her parents were keen amateur Gilbert and Sullivan performers.

‘Gilbert and Sullivan!’ said Biddy, sniffing.

She had a job now too, but it was just part time in a cake shop. Cherry’s mum tried to be friendly with my mum, but Biddy wasn’t having any. She felt they put on airs and considered themselves a cut above us. I wasn’t allowed to invite Cherry back. I wasn’t allowed to have

anyone

in to play, not unless Biddy was there. She didn’t get home till quarter to six now, but I had a key to let myself in.

Lots of the children in my class had similar keys. They wore them on strings round their necks under their vests. People called them latchkey kids. I thought

I

was a latchkey kid but Biddy soon put me right.

‘

You’re

not a latchkey kid! As if I’d let you go out with a grubby piece of string round your neck! You have a proper real leather shoulder purse for

your

key!’

I had to wear the purse slung across my chest. It banged against my hip when I ran and it was always a worry when I had to take it off for PT but I had to put up with it.

I didn’t mind letting myself in at all, though there was always an anxious moment reaching and trying to turn the key in the stiff lock, jiggling it this way and that before it would turn. But then I was in and the flat was mine. It wasn’t empty. It was full of my imaginary friends.

I wasn’t allowed to cook anything on the stove in case I burned myself, but I could help myself to bread and jam or chocolate biscuits or a hunk of cheese and a tomato – sometimes all three snacks if I was particularly starving. Then I was free to play with my friends. Sometimes they were book friends. I had a new favourite book now,

Nancy and Plum

by Betty MacDonald. Nancy was a shy, dreamy girl of ten with long red plaits, Plum was a bold, adventurous little girl of eight with stubby fair plaits. They were orphans, badly treated by horrible Mrs Monday, but they ran away and were eventually adopted by a gentle kindly farmer and his wife.

I read

Nancy and Plum

over and over again. I loved the parts where they imagined elaborate dolls for their Christmas presents or discussed their favourite books with the library lady. Nancy and Plum became my secret best friends and we played

together

all over the flat. Whenever I went on a bus or a coach ride, Nancy and Plum came too. They weren’t cramped up on the bus with me, they ran along outside, jumping over hedges, running across roofs, leaping over rivers, always keeping up with me.

When Nancy and Plum were having a well-earned rest, I’d play with some of my

own

characters. I didn’t always make them up entirely. I had a gift book of poetry called

A Book of the Seasons

with Eve Garnett illustrations. I thought her wispy-haired, delicate little children quite wonderful. I’d trace them carefully, talking to each child, giving her a name, encouraging her to talk back to me. There were three children standing in a country churchyard who were my particular favourites, especially the biggest girl with long hair, but I also loved a little girl with untidy short hair and a checked frock and plimsolls, sitting in a gutter by the gasworks.

Eve Garnett drew her children in so many different settings. I loved the drawings of children in window seats. This seemed a delightful idea, though I’d have got vertigo if I’d tried to perch on a seat in our living-room window, looking down on the very busy main road outside. I loved the Garnett bedrooms too, especially the little truckle beds with patchwork quilts. I copied these quilts for my own

pictures

and carefully coloured in each tiny patch.

I’d sometimes play with my dolls, my big dolls or my little doll’s house dolls – but perhaps the best games of all were with my paper dolls. I don’t mean the conventional dolls you buy in a book, with dresses with little white tags for you to cut out. I

had

several books like that: Woolworths sold several sorts – Baby Peggy and Little Betsy and Dolly Dimples. I scissored my fingers raw snipping out their little frocks and hats and dinky handbags and tiny toy teddies, but once every little outfit was cut out, white tags intact, I didn’t really fancy

playing

with them. I could dress them up in each natty outfit, but if I tried to walk them along the carpet or skate them across the kitchen lino, their clothes fell off all over the place. Besides, they all seemed too young and sweet and simpering for any of

my

games.

My favourite paper dolls came out of fashion books. In those days many women made their own clothes, not just my grandma. Every department store had a big haberdashery and material department, with a table where you could consult fashion pattern catalogues – Style, Butterick, Simplicity and Vogue. At the end of every season each big hefty book was replaced with an updated version but you could buy the old catalogues for sixpence. Vogue cost a shilling because their designs were more stylish, but I didn’t like them because

their

ladies weren’t drawn very realistically, and they looked too posh and haughty.

I loved the Style fashion books. Their ladies were wonderfully drawn and individualized, with elaborate hairstyles and intelligent expressions. They were usually drawn separately, with their arms and legs well-displayed. It was highly irritating finding a perfect paper lady with half her arm hidden behind a paper friend. She’d have to suffer a terrible amputation when I cut her out.

I cut out incredibly carefully, snipping out any white space showing through a bent elbow, gently guiding my sharp scissors around each long curl, every outspread finger, both elegant high heels.

I’d invent their personalities as I cut out each lady. It was such an absorbing ritual I was lost to the world. I remember one day in the summer holidays, when Biddy was out at work and Harry was

off

work for some reason, sitting at the living-room table with his horse-racing form books and his

Sporting Life

, working out which bets he was going to put on. He seemed as absorbed in his world as I was in mine. I forgot all about him until he suddenly shouted, ‘For Christ’s sake, do you have to keep snip-snip-snipping?’

I jumped so violently I nearly snipped straight through my finger. I cut out my paper ladies in my bedroom after that, even when I was alone in the

flat

. I spread each lady out on my carpet. I cut out girls too, especially the ones with long hair, though plaits were an exceptionally fiddly job. I seldom paired them up as mothers and daughters. They were simply big girls and little girls, living in orphanages or hostels or my own kind of invented commune. There would be a couple of men too, but they were usually rather silly-looking specimens in striped pyjamas. No one sewed men’s suits from scratch, not even my grandma, so you only got nightclothes and the occasional comical underwear. I certainly didn’t want any grinning goofy fools in white underpants down to their knees and socks with suspenders hanging round

my

ladies.

I didn’t bother with the boys either, though there were more of them in short trousers. I did have a soft spot for the babies though, and cut out the prettiest. Then I could spend hours at a time whispering my games. My favourite of all my paper girls was a bold, long-haired lady called Carola, in a lacy black bra and a half-slip. She was a naughty girl and got up to all sorts of adventures. I’d carry her everywhere with me, tucking her carefully inside my book.

Which of my characters has paper girls with special flower names?

It’s April in

Dustbin Baby

.

I carefully cut out long lanky models with skinny arms and legs, my tongue sticking out as I rounded each spiky wrist and bony ankle, occasionally performing unwitting amputations as I went.

Sylvia found me an old exercise book and a stick of Pritt but I didn’t want to make a scrapbook. I wanted to keep my paper girls free. They weren’t called Naomi and Kate and Elle and Natasha. They were my girls now, so I called them Rose and Violet and Daffodil and Bluebell.

I seem overly fond of the name Bluebell. It’s also the name of Tracy Beaker’s doll and Dixie’s toy budgerigar. Sorry I keep repeating myself!

16

Mandy

I WAS TAKEN

to the cinema regularly. I didn’t go to the children’s Saturday morning pictures – Biddy thought that was too rowdy. I watched proper adult films, though the very first time I went I disgraced myself. This was at the Odeon in Surbiton, when I was three and still living at Fassett Road. All five of us – Biddy, Harry, Ga, Gongon and me – went to see some slapstick comedy. I didn’t do a lot of laughing.

I thought it was all really happening before my very eyes (remember, we didn’t have television in those days). I found it very worrying that these silly men were sometimes so big that their whole heads filled the screen. I couldn’t work out where the rest of their bodies were. I knew I didn’t want these giants coming anywhere near me. Then they shrank back small again. They were running away, pursued by even scarier men with hatchets. They dodged in and out of traffic in a demented fashion, then ran into a tall block of flats, going up and down lifts, charging along corridors, through rooms to the windows. They climbed right outside, wobbling on the edge. The camera switched so you

saw

things from their point of view, looking down down down, the cars below like little ants. The audience

laughed

. I screamed.

I had to be carted out of the cinema by Biddy and Harry, still screaming. They were cross because they’d wasted two one-and-ninepenny tickets.

‘Why did you have to make such a fuss?’ said Biddy.

‘The man was going to fall!’ I wailed.

‘It wasn’t

real

,’ said Harry.

It took me a while to grasp this, which was odd seeing as I lived in my own imaginary world so much. However, I grew to love going to the cinema, though I never liked slapstick comedy, and I still hate it whenever there’s a mad chase in any film.

We saw

Genevieve

together, and all three of us found that very funny indeed. Biddy said she thought Kay Kendall was beautiful. I thought this strange, because Kay Kendall had short dark hair. I didn’t think you could possibly be beautiful unless you had blonde fairy-princess hair way past your shoulders.

Harry quite liked musicals but Biddy couldn’t stand anything with singing, so Harry and I went to see

Carousel

and

South Pacific

together. I thought both films wondrously tragic. I don’t think I understood a lot of the story but I loved all the romantic parts and all the special songs.

When Harry was in a very good mood, he’d sing as he got dressed in the morning – silly songs like ‘Mairzie Doats an Doazie Doats’ and ‘She Wears Red Feathers and a Hooly-Hooly Skirt’, and occasionally a rude Colonel Bogey song about Hitler. But now he’d la-la-la the

Carousel

roundabout theme tune while whirling around himself, or he’d prance about in his vest and pants singing, ‘

I’m going to wash that man right out of my hair

.’

I can’t remember who took me to see

Mandy

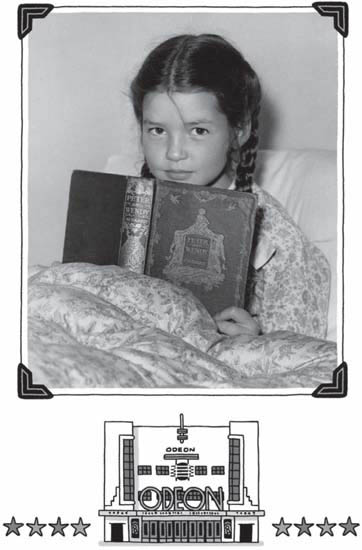

. It was such an intense experience that the cinema could have crumbled around me and I wouldn’t have noticed. I was

in

that film, suffering alongside Mandy. She was a little deaf girl who was sent away to a special boarding school to try to learn how to speak. There was a big sub-plot about her quarrelling parents and the developing relationship between Mandy’s mother and the head teacher of the school, but that didn’t interest me. I just watched Mandy, this small sad little girl with big soulful eyes and dark wispy plaits. I cried when she cried. When she mouthed ‘Man-dee’ at the end of the film, I whispered it with her.