Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

John Aubrey: My Own Life (19 page)

My stammer has been troublesome since these mishaps.

. . .

April

I have gone

105

with Mr Hobbes’s brother Edmund to visit the house where my friend the eminent philosopher of Malmesbury was born. I hope to prevent mistakes or doubts hereafter as to the birthplace of this famous man. So we went into the very chamber where his brother says Mr Hobbes was born, in their father’s house in Westport, which points into (or faces) the horse fair, the farthest house on the left as you go to Tedbury, leaving the church on your right. It is a firm house, stone-built and tiled: one room (with a buttery or the like within) and two chambers above. It was in the innermost of these chambers that Mr Hobbes first drew breath on Good Friday 5 April 1588. It is said his mother took fright at the invasion of the Spanish Armada and went into labour early.

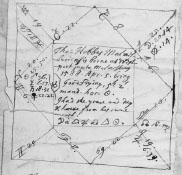

Mr Hobbes’s horoscope

106

is Taurus with a satellitium of five of the seven planets in it. It is a maxim of astrology that a person who has a satellitium in his ascendant becomes more eminent in his life than an ordinary person who does not. Oliver Cromwell had this, same as Mr Hobbes.

. . .

May

After less than nine months as Lord Protector, Richard Cromwell has fallen from power. He had no confidence in the army, and the army had none in him. Now one of the army’s factions has undone him. He refused the army’s demand to dissolve the recently elected Parliament, so troops assembled at St James’s Palace to force his hand. The recent Parliament has been dissolved and the Parliament of 1648 has been recalled. The Parliament of 1648 is called the Rump Parliament because it is what was left after the Long Parliament was purged of all members hostile to putting the late King on trial for high treason.

. . .

25 May

On this day the Rump Parliament agreed to pay Richard Cromwell’s debts and give him a pension in return for his resignation as Lord Protector.

. . .

I have made my will and settled my estate on trustees, and intend to leave the country to see the antiquities of Rome and Italy. When I return, I will marry, since I am now thirty-three years old and I must secure my fortune in this world.

. . .

July

Mr Stafford Tyndale

107

has written to me from Alençon. He urges me to join him in Paris. He says I should come abroad now while times are favourable and travel cheap: it will be much cheaper and safer to travel in company than alone. He says that if I allow myself just 200 li. a year I can live and travel like a prince in the company he will introduce me to. Convinced I will have a rambling fit before I die, he insists that if I do not take this opportunity I will never have so good a one again. He sends his respects and services to my mother.

. . .

My mother, to my inexpressible grief and ruin, has hindered my plan to travel abroad. She simply forbids me to go, and I feel I cannot disregard her wishes.

Dis aliter visum

(it seemed otherwise to the Gods).

. . .

I have sold the old manor

108

of Burleton in Herefordshire, which I inherited from my father, to Dr Willis for 1,200 li.

. . .

I have sold the smaller manor of Stretford, which I inherited from my father, to Herbert Croft, Lord Bishop of Hereford. I sold it to pay debts, but in part I am glad to be free of another property: ownership comes accompanied by weighty responsibilities that keep me from my studies.

. . .

I am taking a course of lessons with the Danish mathematician Nicolas Mercator, but truly my life is dominated by debts and lawsuits –

opus et usus

– borrowing of money and perpetual riding. I have no time to settle to my studies.

. . .

I am sharing lodgings

109

in London with my friend Tom Mariett, of Whitchurch in Warwickshire. He is in correspondence with Prince Charles in exile and I have seen letters in the Prince’s own hand in our rooms. Tom and Colonel Edward Massey are tampering daily with General Monck, commander-in-chief of the Parliamentary forces, to see if he will be instrumental in bringing the Prince back to England, but they cannot find any inclination or propensity to this purpose in General Monck. Late every night in bed I hear an account of all these transactions. Sometimes I think I should commit these accounts to writing while they are still fresh in my memory.

. . .

Michaelmas

I am an auditor

110

, or listener, at Mr Harrington’s new Rota Club, which is a coffee club that meets every night in the Turk’s Head in the New Palace Yard, at one Mr Miles’s house next to the stairs. Here there is an oval table with a hole cut in one side for Mr Miles to stand and serve the coffee. These meetings are a forum for exchanging republican views, and the discourses I have listened to at them are the most ingenious and smart that I have ever heard, or expect to hear.

After the meetings we often repair to the Rhenish-wine house.

At our meetings we have a formal balloting box and we ballot about how things should be carried by tentamens or experiment. The room is crammed full every evening, as full as it can be, with gentlemen diverting themselves with philosophical or political discussions.

My Trinity College friend

111

Sir John Hoskyns is a member of the Rota Club, as is the learned Dr William Petty. Dr Petty troubles Mr Harrington with his arithmetical proportions and ability to reduce politics to numbers. It seems that every day in the coffee house, Mr Harrington’s

Commonwealth of Oceana

and Henry Nevill’s discourses make new proselytes.

Mr Harrington recently printed a little pamphlet called

Divers Modells of Popular Government

, and now another called

The Rota

. His doctrine is being taken up, the more because there seems to be no possibility of restoring the monarchy. And yet the greater part of the Parliament’s men hate Mr Harrington’s design for allocating political office through rotation by balloting. The Parliament’s men are cursed tyrants in love with the power they would lose if Mr Harrington’s method of rotation came in. The model provides that a third of the senate should be replaced every year by ballot, so that it will be completely renewed every nine years, and no magistrate should continue in office more than three years. There is nothing invented that is more fair and impartial than choosing by ballot. The pride of senators appointed for life is insufferable and they can grind anyone incurring their ill will to powder. They are hated by the army and their country: their names and natures will stink for years to come.

. . .

I have often heard Mr Harrington speak of the late King at the Rota meetings, with the greatest zeal and passion imaginable. Mr Harrington was so grief-stricken by the King’s execution that he contracted a disease: never did anything touch him so closely.

PART V

Restoration

Anno 1660

3 February

ON THIS DAY

1

General Monck entered London, around 1 p.m., with none opposing him.

. . .

9 February

General Monck’s forces, on the Rump Parliament’s orders, pulled down the city gates and burnt them. This action will make him odious to the people of London.

. . .

11 February

General Monck has apologised for the destruction of the city gates.

. . .

The Rump Parliament invited General Monck to the House, where a chair was set for him, but he would not sit down, out of modesty. They invited him to a great dinner, at which Members of Parliament stayed until the early hours of the morning, but suspecting treachery, General Monck did not attend.

. . .

Someone anonymous

2

has written these words on the door of the House of Commons:

Till it be understood

What is under Monck’s hood

The citizens putt in their hornes.

Untill the ten days are out

The Speaker haz the gowt,

And the Rump, they sitt upon thornes.

. . .

Threadneedle Street was crammed all day long with multitudes crying: ‘A free Parliament! A free Parliament!’ The air was ringing with the crowds’ clamours. Around seven or eight in the evening, General Monck, after being nearly knocked from his horse, addressed them thus: ‘Pray be quiet, yee shall have a free Parliament!’ Then a loud holler went up and all the bells in the city were rung, and bonfires were lit in celebration. I saw little gibbets set up and roasted rumps of mutton and very good rumps of beef. In the streets the people drank to Prince Charles’s health, even on their knees.

. . .

The news has spread

3

to Salisbury, and on to Broad Chalke, where they made a great bonfire on the top of the hill. From there the news travelled to Shaftesbury and Blandford, and so to Land’s End: perhaps this is what it has been like all over England.

. . .

My bedfellow Tom Mariett insists that General Monck did not intend the restoration of the monarchy when he first came from Scotland to England, or to London, any more than his horse did! But shortly after finding himself at a loss, and made odious to the city by the Parliament’s ordering him to pull down the gates and burn them, he made up his mind in favour of Prince Charles becoming King.

. . .

The members of the Long Parliament who were purged in 1648 on account of their hostility to putting King Charles on trial have been readmitted under General Monck’s protection. So the Rump Parliament is no more and the Long Parliament is restored.

. . .

Mr Harrington’s Rota Club

4

has met for what I think will turn out to be the last time. Ever since General Monck’s coming in, debate on republican government and the Commonwealth has ceased abruptly. Whereas before those airy models of government were so hotly debated at the Turk’s Head, now those debates have fallen silent. Soon it will be treason to hold such meetings. At the breaking up of his club, Mr Harrington says, ‘Well, the King will come in. Let him come in and call a Parliament of the greatest Cavaliers in England, so they be men of estates, and let them sit but seven years, and they will all turn Commonwealth men.’

. . .

16 March

On this day the Long Parliament called for free elections and its own dissolution.

. . .

Mr Milton’s impassioned work

The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth

has been printed but the people have turned strongly against republicanism. Mr Milton is a spare man, of middling stature, scarcely as tall as I am.

. . .

Samuel Pordage

5

, whom I know well since he is head steward of the lands of the Earl of Pembroke, has given me his translation into English of Seneca’s

Troades

(

The Trojan Women

).