John Aubrey: My Own Life (23 page)

Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

. . .

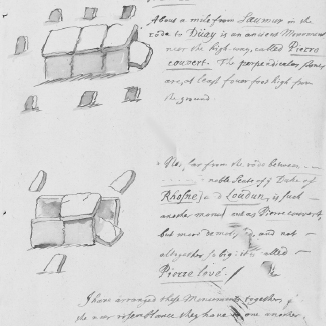

About a mile

3

from Saumur on the road to Doué-la-Fontaine is an ancient monument near the highway called Pierre Couverte. The perpendicular stones are at least four foot high from the ground.

. . .

Not far from the road

4

between the noble seat of the Duke of Rhône and Loudon is another monument like Pierre Couverte, but more demolished and not altogether so big. It is called Pierre Levée.

. . .

October

I have paid

5

for my passage from Dieppe and will return to England.

. . .

I am back in England.

I hear that Mr Hooke’s

6

position as the Royal Society’s Curator of Experiments has been confirmed for life, and that he has been chosen as Professor of Geometry at Gresham College. This is excellent news, since his head lies much more to geometry than arithmetic.

I have seen Mr Hobbes

7

and encouraged him to write about the Law. I said I think it a pity that he who has such a clear reason and working head has never taken into consideration the learning of the laws. At first he said he did not think he was likely to live long enough for such a difficult task – he is now seventy-six years – but I presented him with Lord Bacon’s

Elements of the Law

, to inspire him. He was pleased with the book and is reading it.

. . .

I have seen Mr Hobbes again and he showed me two clear paralogisms in Lord Bacon’s

Elements of the Law

, one of them on the second page, but whether or not he will write his own treatise on law I cannot tell.

Mr Hobbes always has

8

very few books in his chamber. I have never seen more than half a dozen there when I visit him. Homer and Virgil are commonly on his table, sometimes Xenophon. He has described to me how he works. He sets about thinking and researching one thing at a time (sometimes for a week or fortnight). He rises about seven, has his breakfast of bread and butter, then takes a walk meditating until ten. In the afternoon he writes down his thoughts.

. . .

My friend Mr George Ent

9

, who is still in Paris, writes to say he might have found a suitable French-speaking boy servant for me named Robert, to replace the one I brought back from Paris myself, who is no good. He will send me a copy of Andrea Palladio’s

I quattro libri dell’architettura

(

The Four Books of Architecture

), which was first published in Venice in 1570, as soon as he can. Book I was published in English last year.

. . .

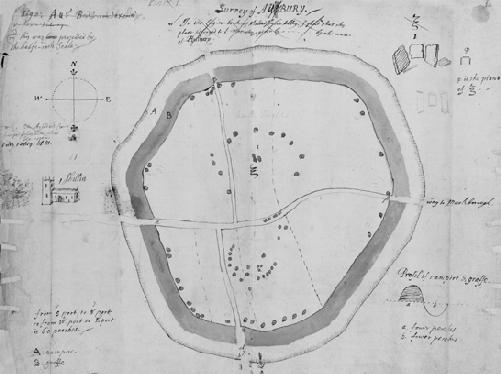

I have made a survey of Avebury with a plane table (helped exceedingly by my neighbour Sir James Long). The plane table provides a solid, level surface on which to make drawings.

. . .

I have written

10

upon the spot about the stones at Avebury, because there is no way to retrieve their meaning except through comparative antiquities. History is good however made (

Historia quoquo modo facta bona est

). I have written, as I rode, at a gallop. I hope the faithfulness and novelty of my words will make some amends for any incorrectness in style.

The hinge for my discourse on Avebury is Mr Camden’s description of Kerrig y Druid (or Druid-Stones) in his

Britannia

, published in 1586. I wish I could journey to north Wales to see the stones Mr Camden writes about, and compare them with what I have seen and written about at Avebury.

The similarity between

11

the name ‘Avebury’ – ‘Aubury’ (as it is written in the ledger book of Malmesbury Abbey) – and my own ‘Aubrey’ does not escape my notice. ‘Au’ or ‘Aub’ in old French means white and is a translation of the Latin

albus

. The whiteness of the soil about Avebury seems to countenance this etymology. But here in my mind’s eye I can see the reader of my diary smiling to himself, thinking how I have stretched the place name to be my own, not heeding that there is a letter’s difference, which quite alters the signification of the words. I see my reader’s scornful smile. I must obviate it with arguments from etymology. I hope no one could think me so vain! I have a conceit that ‘Aubury’ is a corruption of Albury (meaning old-bury, or the old borough).

. . .

I have made a close study

12

of Walter Charleton’s

Chorea Gigantum, or the Most Famous Antiquity of Great Britain, Vulgarly Called STONE-HENG, Standing on Salisbury Plain, Restored to the Danes

, which was printed at the Anchor in the New Exchange last year (1663). He is mistaken in his claim that the stones are ‘unhewen as they came from the quarry’. They are hewn!

Mr Charleton claims

13

that Stonehenge was built by the Danes as a court of election. He imagines that persons of honourable condition gave their votes in the election of their king, standing in a circle on the columns of stones. But this is a monstrous height for the grandees to stand! They would have needed to be very sober, have good heads, and not be vertiginous to stand on those upended stones! I cannot believe Mr Charleton is right.

. . .

I went back to Stanton Drew to see the stone monument there that I knew as a child. The stones stand in plough land. The corn was ripe and ready for harvest at this time of year, so I could not measure the stones properly as I wished. The villagers break them with sledges because they encumber their fertile land. The stones have been diminishing fast these past few years. I must stop this if I can.

The diameter of the stone circle is about ninety paces. I could not find any trench surrounding it, as at Avebury and Stonehenge.

. . .

Southward from Avebury

14

, in the ploughed field near Kynnet, stand three huge upright stones perpendicularly, like the stones at Avebury. They are called the Devil’s Coytes.

. . .

I have been to visit Mr Thomas Bushell at his house in Lambeth. He is about seventy now, but looks hardly sixty and is still a handsome proper gentleman. He has a perfect healthy constitution: fresh, ruddy face and hawk nose. He is a temperate man. He always had the art of running in debt, but money troubles oppress him now. He has never been repaid for the money he spent in the King’s cause during our late wars, and he has been in flight from his creditors ever since.

How well I remember

15

my visit to his grotto at Enstone in 1643. I hear the Earl of Rochester has the statue of Neptune that used to be there now, and that he looks after it very well. I should ask old Jack Sydenham, who was once Mr Bushell’s servant, for the collection of remarks of several parts of England that Mr Bushell prepared. They may help my own collection.

. . .

6 November

The weather today has been terrible: very stormy.

I missed seeing

16

my friend Mr Tyndale, who has been in London these past few days. He did not realise I was here until the day before he had to leave, and I was remiss in not contacting him. He had letters and a box to deliver to me, which he wishes me to pass on to his sister.

. . .

December

This Christmas I have seen again at Wilton, in Mr Hinton’s private garden, blossoms on the thorn bush that he grew from a bud of the Glastonbury Thorn, before it was cut down and burnt by Parliamentarian soldiers in the civil war.

Men say that the Glastonbury Thorn grew when Joseph of Arimathea visited Glastonbury with the Holy Grail and thrust his staff into Wearyall Hill. The tree flowered twice a year: in winter as well as in spring. Before it was destroyed, one of its budding branches was sent to the monarch each Christmas.

The bush in Mr Hinton’s garden

17

gives out enough blossoms to fill a flowerpot, and I have sent some to my mother as a present. In this small way I keep memory of the ancient custom alive.

. . .

Monday after Christmas

My horse almost killed me, and I have lacerated my testicle, which is likely to be fatal! My stammer has been terrible since.

. . .

My testicle is healing.

. . .

The widow of

18

the Oxford mathematical instrument maker, Christopher Brookes, has given me a copy of the pamphlet he printed in 1649, ‘A new quadrant of more natural ease and manifold performance than any other heretofore extant’.

. . .

Anno 1665

Candlemas Eve

Looking on a serene sky

19

this evening, I suddenly noticed a nubecula, much brighter than any part of the

via lacteal

, and about five times as big as Sirius. I shall show it to my neighbour Sir James Long tomorrow night. When the moon shines not too bright, it is very easily seen. It lies almost in the right line, between the bright star of the little dog and the constellation of Cancer.

. . .

15 February

Mr Samuel Pepys

20

, proposed at the last meeting, was unanimously elected and admitted as a Fellow of the Royal Society today.

. . .

March

Sir John Hoskyns

21

has been offered some three or four of the late Mr William Dobson’s paintings for sale by Mr Gander, which he knows I might be interested in buying. One of them is of the clerk of the Oxford Parliament, good, but somewhat defaced. He says if I will pay 10 li. the portraits can be reserved for me until I go and see them and agree a price, or else have my deposit returned.

. . .

The poet Sir John Denham

22

has married for the second time. His wife, Margaret Brookes, is a beautiful young lady, but Sir John is ancient and limping.

. . .

4 March

On this day England declared war on the Netherlands. The cause is mercantile competition.

. . .

June

I have been to see

23

young Lord Rochester, currently imprisoned in the Tower, for attempting to abduct the heiress Elizabeth Malet. Sometimes his actions are extravagant, but he is generally civil enough. He reads all manner of books and is a wonderful satirist.

. . .

The Royal Society has suspended its Wednesday meetings because so many members have left London fearful of the plague.

. . .

August

Mr Wenceslaus Hollar

24

has now finished engraving the portrait of Mr Hobbes I lent him. He has shown it to some of his acquaintances, and it is a very good likeness. The printer demurs at taking it, so Mr Hollar feels all his labour lies dead within him, but he has made a dozen copies for me.

. . .

There is plague in London.

In Mr Camden’s

Britannia

25

there is a remarkable astrological observation, namely, that when Saturn is in Capricornus, a great plague is a certainty in London. Mr Camden, who died in 1623, observed this in his own time, as had others before him. This year, 1665, Saturn is so positioned, as it was during the London plague of 1625.

. . .

November

I have made my first address to Joan Sumner, whom I hope I shall marry and thereby rescue my finances. She is thirty years old and comes from a family of clothiers who live near mine, at Sutton Benger and Seend, which are both close to Kington St Michael.