Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (11 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

• • •

Let’s go back to Caravaggio’s solemn painting. Although the picture taken on its own suggests something sinister, knowing about the artist’s turbulent past, or the murder he had committed, would help you discern the presence of guilt. You would indeed probably need that background information. As Darwin noted, guilt is not the easiest emotion to read on a face. He thought we could detect complex emotions like guilt with our eyes, but when doing so ‘we are often guided in a much greater degree than we suppose by our previous knowledge of the persons or circumstances’.

34

As usual, the great naturalist had a point. When you look at brain scans, unless you know what you are supposed to be seeing and are familiar with the nature of the study, the intensity of the light and its position are rather meaningless.

Guilt has many shadings, and there are very many different scenarios and behavioural conditions in which it could be measured. The question remains as to whether all these different types of guilt are processed in the same location and by similar processes. This is why if you compare brain scans originating from several separate studies you will find the results differ, sometimes only marginally, but on occasion to a noticeable degree. This brings me to a general observation about the measurement of emotions in fMRI.

When your emotions are being measured inside a scanner, you are often asked to perform a distinct task, for example watching images, remembering events or, as we have seen in studies of morality, making ethical choices such as whether to save a child’s life. However realistic these tasks may be in their approach, they can only ever be experimental reproductions of situations that are much more complex, but also more direct and urgent, when they happen in real life. The tasks in the scanner are convenient substitutes for authentic fragments of life. There remains a gap between the two and so far we don’t know what the brain activity of the real version of the emotion looks like. Moreover, the blob in the brain scan is actually a representation of the

average

result computed from measurements taken in dozens of individuals recruited for a study. The final image you see is not the oxygen flow of one brain, but the statistically significant oxygen flow across all the participants in the study. Yet guilt works at the level of the individual. It is such a personal, uniquely private emotion that it is hard to imagine it diluted with the guilt of others. Not everyone feels guilt with the same intensity. There are individuals who, without being psychopaths, are simply less prone to guilt.

Finally, there is another analogy I like using when I try to describe what we are effectively seeing when we gaze at an fMRI scan. I think it’s like being at the top of the Empire State Building and having a 360-degree night view of the illuminated New York skyline without binoculars. We can appreciate the contour of Manhattan, see more or less where Queens ends and Brooklyn begins, point at New Jersey across the Hudson. Our eyes can perhaps follow the dividing line of Broadway and the rushing trail of cars and spot the dark hole of Central Park. We see the lights of New York life flickering on and off in different areas of the city at different times, and can identify its busiest periods and when things are quieter. Given a pair of attentive eyes and good knowledge of the streetmap we could pinpoint the origin of the glow. We might recognize the lights as coming from a loft somewhere between Canal Street and Washington Square, or up in Harlem and the Upper East Side.

But what we can’t see is what actually goes on inside the buildings, the lives and motivations of the people turning on those lights and giving colour and movement to the city. We have no idea if the light is a lamp, a candle or a chandelier or whether it is coming from a bedroom, a kitchen or a living room. We also don’t know who turned it on and why: it might be illuminating an intimate dinner or a party or a serious family conversation; it might be on because a child is afraid to sleep in the dark, or because somebody simply forgot to turn it off. So, from on top of the Empire State Building and through an fMRI scan alike, the view is spectacular, but not fully revealing. Right now, the view achieved through an fMRI is crude and approximate. With time, the technique will be refined, giving greater precision and detail on a smaller scale, allowing its potential to be realized.

In sum, when you read expressions like ‘this region of the brain

lights up

when you feel fear’ (or anger or any other emotion), it is only popular, overused parlance aiming to simplify the complicated underpinnings of magnetic resonance. For me at least, there’s no way gazing at an fMRI image can help draw definite conclusions about the sense of guilt, nor map its exact locus, let alone find out how to assuage it.

The moral brain

At the beginning of the chapter, I explained how guilt appeared to me in disguise in a dream and how the inspiration of Freud’s theory on the interpretation of dreams came to him the morning after having had a guilt-themed dream himself, the dream about his patient Irma and the injection.

Psychoanalysis enthusiasts have for a long time tried to find confirmation of Freud’s ideas in current neuroscience research. They point out that present-day studies of lesions and modern visualization techniques are drawing a map of the brain that approximately coincides with Freud’s structural theory of the mind.

35

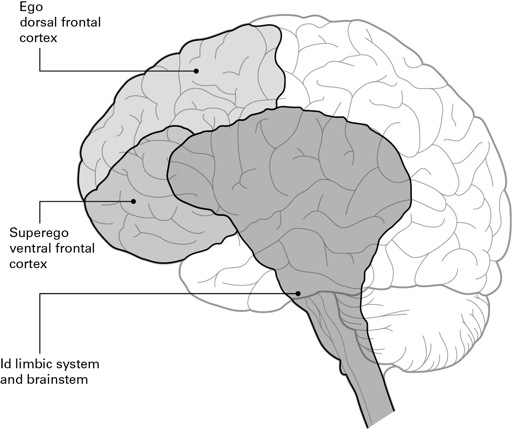

The id, the ego and the superego postulated by the Viennese physician are finding their neuro-anatomical seats. By comparing Freud’s diagram with today’s collected data on the role of brain regions, psychoanalysts have sketched the following general map (Fig. 6). As previously thought, the id would comprise the most internal parts of the brain, such as the stem areas and the limbic system. The ego would lie in the most dorsal part of the prefrontal cortex, and in the rest of the somato-sensory cortex, areas which provide a sense of self and enable perception of the outer world. The ventromedial frontal part of the brain – which overlaps with the areas mapped by the imaging studies on guilt – corresponds to Freud’s concept of the superego, the moral apparatus that constrains and prohibits the most instinctual drives. Within this framework, it is not surprising that guilt, as a moral sentinel guarding against or preventing inappropriate conduct, would sit somewhere in areas overlapping the orbitofrontal cortex.

Fig. 6 A brain-map view of Freud’s structure of the mind (diagram adapted from Solms, 2004)

In the past ten years or so, the number of brain-imaging studies attempting to address the neural basis of morality or moral emotions has been impressive. From regret to guilt and shame, a whole list of moral emotions and concepts have been under scrutiny in a brain scanner. Even social comparison emotions such as envy and

Schadenfreude –

the former being displeasure at someone else’s good fortune, the latter the relief or joy we feel when the envied person falls from grace – have been investigated.

36

A few moral psychologists have proposed the idea that all human beings share a basic, universal sense of morality – a concept reminiscent of philosopher Immanuel Kant’s ‘innate morality’ –

and that the brain may even be the seat of a ‘moral organ’ that helps us choose what is right and what is wrong relying upon unconscious intuitions.

37

The question arises: is morality something ingrained in our biological constitution, or is it something that manifests in society as a direct consequence of behaviour patterns that demand some sort of regulation or norm? Do values have their origin in the brain? Brain-imaging studies of emotions as complex as guilt and concepts as multifaceted as morality are definitely exciting, but in most cases only explorative. What does it actually mean that guilt sits in the orbitofrontal cortex or overlaps with the ventromedial PFC? Are regret and guilt similar because of overlapping fMRI data?

What imaging studies do is delimit by trial and error the area engaged in that emotion.

There is another issue to raise. The idea that the brain works by the operation of distinct modules, each in place for the execution or adjustment of a particular function, is irresistible, but not consistent with what we know of its actual

modus operandi

. From the moment the first connections were made between certain areas of brain tissue and function – for example the discovery of the language region – it was assumed that more and more specialized regions would be identified. But even though the brain displays a fair degree of specialization, the way the brain works is by the integration of connecting pathways and their interactive nature. The case of the emotions is no exception. One region may play a part in several emotions and the neural activity related to each emotion is spread across several regions. Research is moving towards the discovery of

networks

for emotions, consisting of regions working in parallel. One region is, say, specialized for or more strongly involved in one emotion, but plays simultaneously a less prominent role in other emotions.

38

Over time, the scale and definition of brain imaging will improve. We will also come to redefine and improve the way we observe and measure guilt. For now, we need to accept and take for granted that the exact, confined location of guilt, or any other emotion, is still an estimate: how good an estimate being dependent on the sophistication of current technology and the scientist’s knowledge, skill and interpretative judgement.

39

Coda

In his

Recipes for Sad Women

, Hector Abad notes with resignation the impossibility of finding dinosaur meat nowadays.

40

He does so because dinosaur meat, together with mammoth’s milk, he says, is the only effective remedy to assuage an insistent sense of guilt. It doesn’t take long to grasp the irony of such culinary analogy. The chances of getting hold of that prehistoric flesh are so remote that the possibility of assuaging guilt fades as soon as it has been glimpsed.

Abad offers an alternative. Another remedy for guilt is the flesh of a coelacanth, a very rare fish that everyone had thought extinct since the dinosaur era. He reports having come across one himself while fishing in the Indian Ocean in 1946. After some research, he found out its taxonomic name: Latimeria chalumnae, after Ms Marjorie Latimer from East London, South Africa, who had made the initial discovery eight years earlier. A marinated fillet of this rare fish does wonders in fighting guilt, says Abad, its effect lasting about thirty-eight months. Even just a bite is effective.

Apart from these improbable recipes, there are other ways to try to assuage guilt. In the legal system, as we have seen, the perpetrators of a crime may find their punishment and rehabilitation serve to redeem them from guilt (though this will not be the case for psychopaths). But forgiveness remains perhaps the best antidote to guilt: the forgiveness we receive from others, and the forgiveness we may afford to grant ourselves. Caravaggio painted his request for forgiveness. After my museum visit, having absorbed the meaning of Caravaggio’s life and painting, I rushed to my room. I had been extremely apologetic when cancelling my acceptance of Esra’s invitation, but I felt something had been left undone. So, I decided to write a new letter to her. I reckoned it was the best and only way for me to try to make reparation for my act of negligence and attain some form of forgiveness for myself. ‘There is a luxury in self-reproach,’ wrote Oscar Wilde in

The Picture of Dorian Gray

, in which he makes the protagonist write a letter to his lover in search of forgiveness for his cruelly abandoning her after she had given a very bad performance as Juliet. ‘When we blame ourselves we feel that no one else has a right to blame us.’

41

I was completely engrossed in the act of writing that letter. I wasn’t trying to escape judgement or to sweep my guilt under the carpet. Neither did I expect my feeling of guilt to recede fully. I was simply looking for understanding. Instead of letting my guilt sit inside me, it made sense to give space to it in words. I offered again my apologies and explained my reasons as best as I could. I did feel better afterwards.

After filling page upon page, I went out for dinner. It was the last night of my trip. No coelacanth at hand, but very good wine. Then at midnight, I went to bed, in hopes not to face another bad dream. I was ready for a return to London.

3

Anxiety: Fear of the Unknown

Anxiety is the interest paid on trouble before it is due

WILLIAM RALPH INGE

Anxiety is the handmaiden of creativity