Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (14 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

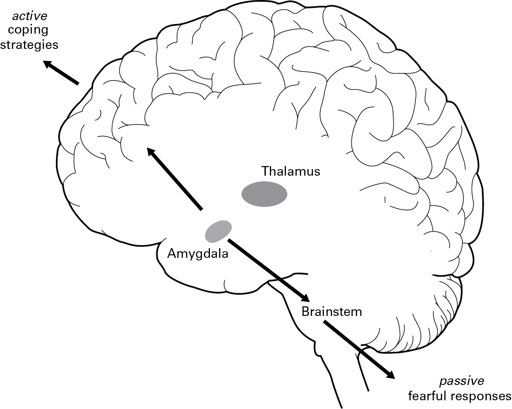

Fig. 8 Anatomy of fear and anxiety

The main region involved is the amygdala, the name being a Greek word which means almond. Appropriately shaped, the amygdala is located at the base of the brain, in the temporal lobe (Fig. 8). To have a better idea of where the amygdala is, imagine an arrow that goes straight through your eye and another that goes through your ear: their point of intersection is the position of the amygdala. The amygdala lies at the core of our emotional life, especially our fearful reactions. If we didn’t have it, we would probably not be scared of anything! Similarly, an impairment in amygdala function prevents us from perceiving emotion. Indeed, a patient with rare lesions in both her amygdalas (we have one in each of our two brain hemispheres) just could not recognize fearful expressions in others’ faces.

20

Despite its small size (about that of your thumbnail), the amygdala has an intricate structure and consists of different parts, each with a different function. For now, just bear in mind that it has a core, called the central nucleus (CeA), and a more external part called the basolateral complex. A conditioned stimulus from the external environment – like the buzzing tone in the fear-conditioning paradigm – first reaches the thalamus, the part of the brain which serves as an integration centre between the outside world and our perception of it. From the thalamus, it travels to the audio-visual cortex where it is processed. But the signal can also follow a shortcut that leads directly to our emotional centres. Indeed, the thalamus has a direct connection to the amygdala, and to be exact, to the basolateral complex. It is here in the amygdala that the emotional memory of the buzzing tone, or whatever our own emotional trigger may be, is stored. From the amygdala, a danger signal is then relayed to the brainstem, which activates your anxious responses.

• • •

Uncovering some of the brain mechanisms underlying an emotion as complex as anxiety is a fascinating endeavour. The fact that we can describe anxiety in terms of neurochemical levels or patterns of neuronal firing in distinct brain regions is the result of inspired, dedicated experiments and a step towards the development of improved diagnostic and therapeutic tools to counter anxiety.

However, much as these experiments on animals serve to dissect a few of its universal components, the lived experience of anxiety, that which seeps deep through our existence as human beings, remains thereby unexplored.

The rats’ freezing reaction is comparable to a condition of paralysis and inaction in humans, but the sense of anguish and impotence, the horrid sensation of helplessness, the feeling that our future is uncertain and unpredictable are difficult to grasp molecularly and reproduce in an experiment. Let alone in a rat! Ultimately, anxiety is also the manifestation of a tacit awareness that something is missing or wrong in our lives, or that our values and aspirations are out of focus or under threat.

Such contrast between scientific investigation and experience is central to the study of emotions. Science provides an outer picture of the scaffolding of emotions, constructed from universal, measurable and reproducible facts, whereas our direct experience of emotions is much akin to living inside the building behind the scaffolding. It is the fruit of our consciousness, or what is otherwise known as phenomenology, and is not entirely amenable to the scrutiny of science.

The wind of anxiety

Knowing the limits of science in exploring anxiety as an internal human condition, I was still in search of ideas and experiences I could identify with, in order to make sense of it. Eventually, I turned to philosophy, and particularly to the field of existential philosophy. This branch of philosophy is concerned with how we, as human beings, act, feel and live in search of meaning for our existence. For existential philosophers, there is no rigid, unconditional theory that defines us. Existence prevails over any kind of essence. Indeed, existentialists reject the primacy of universal laws, such as those of science, believing that we are born to seek and choose purpose in a world which is often messy and disorienting. Similarly, we constantly need to find our own values and our own meaning for our lives.

Of all existential thinkers, German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) is the one who had the biggest impact on me. Heidegger is best known for having written

Being and Time

(1927),

21

which is considered one of the most influential works of philosophy of the twentieth century. The relevance of Heidegger’s thought to the understanding of emotions becomes apparent if we consider the distinction he makes between two main ways of looking at the world, for which he adopted two interesting and innovative terms:

Vorhandenheit

and

Zuhandenheit. Vorhandenheit

, which roughly translates as present-at-hand, is a theoretical understanding of reality. It is how we observe and theorize about things, and how we come to know facts about the world through disinterested examination – the way a scientist would.

Zuhandenheit

, or ready-to-hand, is about how we engage with the world – how we are connected to it through our interactions with objects and people in various circumstances. Heidegger accorded the latter greater power, which is to say that our experience of the world overshadows our scientific knowledge of it. It is what comes first, how we initially get to know the world. Likewise, one could say, our experience of our emotional life prevails over our theoretical grasp of it. Heidegger believed that science cannot fully grasp the lived experience of anxiety.

The idea that anxiety and fear are distinct was clear to him. As he wrote, fear and anxiety are ‘kindred phenomena’ that are often mixed up, but need to be distinguished. Something threatening is ‘fearsome’ if it is encountered as a definite and real entity. By contrast, ‘that in the face of which one is anxious is completely indefinite’. Anxiety does not know what it is anxious about, because the threat is ‘nowhere’ in particular and has no identifiable source.

22

Heidegger granted anxiety high importance. In much the same way that we need to be able to experience fear in the presence of real danger in order to survive, for Heidegger we need anxiety in order to ‘exist at all’ in the world. How is that? Daily we navigate in the world enmeshed in its net of things, people, actions and circumstances. We get up, take our kids to school, go to work, meet our colleagues and friends, go to the gym or the pub, plan a holiday, buy a new piece of furniture for our home, a new CD or the latest phone, and play with our iPad. We are completely absorbed by all this. Heidegger calls this absorption into the world ‘falling’. In simple terms, we ‘fall’ into our routines and, so doing, we tend to overlook, and to stop searching for, the authentic meaning of our lives. Lodged in the ‘inertia of falling’, we turn away from ourselves. We flee from a meaningful life, because it’s easier to do so. We repress anxiety, but ‘anxiety is there. It is only sleeping.’

When it awakes, though, our symbiotic rapport with the world fades. In anxiety, those same things, circumstances and people in the world become irrelevant and disappear. Everything ‘sinks away’. Any previous connection with the world, and any interpretation of it, is put into doubt. It is no wonder that to convey the disquieting feeling of anxiety, Heidegger also used the word

unheimlich

, which means to be out of home, or ‘estranged’ from home.

23

In a bout of anxiety, we are forced to become more self-aware and, in so doing, we reconsider the importance of some of the things that we used to hold so dear and our engagement with them. We question ourselves. Anxiety discloses the world and our condition in it as they are, void of superfluous adornments.

Our anxiety also connects to the future. We are human beings who exist in time, Heidegger insisted. Indeed, we are not anxious about what has happened, or what is about to happen. Instead we become anxious primarily about what

may

happen. Worry often creeps in when we think about the endless chances that we may or may not seize in life. Anxiety is rooted in the realization of our freedom to choose who we want to be and how we want to live. For Heidegger, choice comes with a substantial difficulty, because it is, profoundly, about the type of life that makes us more authentic. It is not simply about what job to take, which house to buy or with whom to share a life. It is about the job, the house and the individual that bring out the highest potentiality for our being, upon which we rely for the achievement of our happiness, one could say. There is no fixed recipe. Only we can understand what is best for us. It is about choosing something for its meaning for us alone and not because it conforms to society’s norms or anyone else’s values.

How many times have we had to face important decisions and been baffled by the possibilities? Sometimes the decision is relatively simple and there are only a couple of options from which to pick. On other occasions there is a lot at stake and the possibilities are less clear. So, for example, think about the time when, on reaching adulthood, you had to settle on a career to follow.

If you were lucky, you may have had a single passion ever since you were a child, a passion you were always able to cultivate. For some, choosing what to be and becoming it involves a more tortuous path. Understanding your true inclinations and following them may be a stressful process.

In truth, being authentic to oneself is an endless challenge that we face, with varying degrees of awareness, day after day. Anxiety is always around the corner; we are in constant negotiation with it.

So, anxiety is simultaneously the starting point on our journey to become our true selves and the awareness that we are alone in an ocean of life possibilities. Dreadful, isn’t it?

When I approached Heidegger, I realized that his description of anxiety paralleled my own personal metaphor of anxiety as a robust wind. The wind that had swept everything away, dislodged me from the carousel of life and left me on an empty, shadowy stage, with just one spotlight, directed at me. His words spoke to me as no experiment could. Ideas and philosophy matched my personal feeling of anxiety more closely than did the laboratory and science.

Take the alternative route

Heidegger definitely made me see the neuroscience of fear and anxiety in a new light, and the consequence was that I began seeking out studies that somehow supported anxiety’s useful role in life and offered practical clues as to how to manage it.

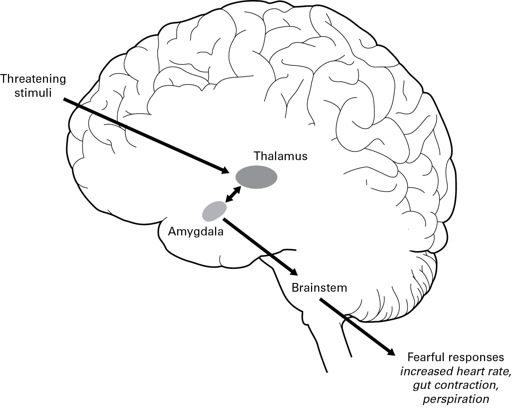

Going back to those rats, I found an interesting series of experiments that refined the original ones, taking them a step further. In one, conducted by the neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux and his colleagues at New York University, rats conditioned to the buzzing tone were given the opportunity to move to another room while the tone was being emitted. If they chose to enter the new room, the tone stopped and the shock did not ensue. After a few such repetitions, the animals learnt the advantage of their new behaviour – choosing to change rooms – and that discovery in turn altered their fear responses. The danger signal stored in the amygdala did not reach the brainstem and did not trigger the freezing reaction. It went instead to motor circuits and incited the rat to take novel actions.

24

What is indeed remarkable in this set of experiments is that the flow of information is effectively rerouted only if the rats take action, and not if they remain passive. It is clear that there are two distinct neural outputs from the amygdala that mediate the impact of the tone, one triggering passive fear reactions, the other facilitating novel actions (Fig. 9). In rodents and humans alike, both pathways are available, but the second one has to be learnt. By engaging this alternative pathway, passive fear is replaced with action, what in the field is known as an active coping strategy.