Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (17 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

Rilke is encouraging us to embrace uncertainties. Accepting and learning to cope with that fundamental and intrinsic aspect of existence is the best approach to living with and through anxiety.

4

Grief: Presence in the Absence

Your absence surrounds me,

like a rope around the throat,

like the sea in which one sinks

JORGE LUIS BORGES

1

Happiness is good for the body, but it is grief which develops the strengths of the mind

MARCEL PROUST

O

ne by one, in a corner of her house-garden, Nonna Lucia, my maternal grandmother, plucks the best fruits off an old fig tree and places them in a straw basket. September is when figs are ripest here in the south-east of Sicily and Nonna has promised me jam to take back to London. I am paying her a visit and I am in charge of reaching to the fruit on the tallest branches, those same branches that I used to climb when I was a child. The fig tree is more or less as old as I am. Like everything else in the garden, it was planted by my grandfather when he and Lucia left their home town to come and live here by the sea. All these years, besides delivering its annual harvest, that tree has also provided the perfect corner of shade for everyone at family gatherings during sultry summer afternoons.

The basket full, when we return inside the house I proceed to peel the crop, eating one or two of those delicious fruits, while Nonna takes a moment to look out to the sea. A strip of water is visible from her kitchen window. Granddad once bought her a telescope and placed it pointing at the sea so that she could spot him as he passed by in his boat during his weekend fishing trips. Always around noon. All Grandma had to do to see him was to peer into it to catch the boat coming into sight.

After all these years I still don’t know if the telescope was there to reassure her, or if Granddad secretly didn’t mind having a private coastguard, checking that everything was all right. In either case, his passage was also a signal that he was on his way back home and about to reach the pier, and that it was time to crush the herbs, boil some water and, when the grandchildren were around, to summon us to lay the table and go and pick fresh parsley, lemons and sage from the garden.

The telescope is still there, but the boat no longer comes into sight, except in the crosshairs of her memory, the memory of a life spent together that lasted for sixty years. Now, there is no more freshly caught fish to bone, neither is there a packed breakfast to prepare for Granddad’s dawn fishing expeditions. Only a proud portrait of him at the helm of the boat hanging on the wall. Underneath it, fresh flowers and a candle. Nonno Nino died in June 2007 at the age of eighty. He lost his life to stomach cancer, after a battle that lasted a little over a year and involved two surgical operations, a lot of bargaining with hope, and a lot of courage. The entire family was saddened by his departure, but for Lucia, his spouse, the separation was tougher because she lost her life companion. When my grandmother stares at the sea from the window, she reaches a place known only to her. ‘Grief makes an hour ten,’ said Shakespeare. ‘Suffering is one very long moment,’ echoed Oscar Wilde in his

De Profundis

. For those in grief, time proceeds at a different pace, the seasons, days, hours and minutes lagging as if the earth itself had slowed in its rotations. Loss tilts the plane of our existence. It is a disorienting experience, an emotional earthquake, capable of upsetting our compass points of reference as we navigate through what remains of life in the absence of that loved one.

When we grieve, we relive memories of moments shared with the person who has died. At first, memories, even the most joyful, are intrusive and can be extremely painful. The ancient playwright Aeschylus once said: ‘There is no pain so great as the memory of joy in grief.’ Memories prompt yearning, and a desire for reunion that cannot be met. At best we try to avoid circumstances, places or activities that remind us of the lost one. Over time, however, acceptance of the reality contributes to coping better and memories are what most preciously helps us bring the lost ones close. Proverbially, time is a cure for grief and sadness.

Grief is an intense emotion which can also be regarded as a process, a trajectory that involves other emotions, like knots to untangle in a chain. Grief ages. It is first young and insistent, then calmer and more discreet. Although there is no prescribed or typical reaction to loss, a large number of bereaved individuals share the experience of a few common stages.

2

First comes denial. You just can’t believe, nor accept, what has happened to you and that the life of someone you love has been snatched away. The loss is unbearably traumatic and denial works like a convenient filter that only lets in what you are able to handle. Then ensues anger, at yourself or others, for not doing enough, for not being able to prevent the death. Turned inward, the anger at yourself often transforms itself into guilt. Finally, we learn how to live with the loss, we frame it, putting into a more distant perspective, we learn how to deal with memories, reaching a level of acceptance. But before that point, which may take a long time to achieve, there is perhaps the slowest, most painful and fragile stage to go through. That is deep sadness.

Down in the mouth

The title of this section is a common idiom, in use in the English language since the mid seventeenth century,

3

to label the feeling of being dispirited, dejected, discouraged, disappointed. All these terms express an emotional transformation involving a theft, a subtraction of some sort.

But there is another familiar set of metaphors denoting sadness that involve motion. We sink, we fall, we descend into low spirits or into the doldrums. We feel down, everything loses vigour and declines, as if at the mercy of a faceless gravity. It’s a downward movement. An overall contrition, and an inward shrivelling. In his chapter on ‘low spirits’, Darwin describes sadness as a state characterized by languid blood circulation, pallor and flaccid muscles. ‘The head hangs on the contracted chest,’ he writes, and ‘lips, cheeks and lower jaw all sink downwards from their own weight’.

4

Indeed, the expression ‘down in the mouth’ finds its tangible correspondence in the micro-movements of our facial expressions. One of the first perceptible signs of sadness is the drawing down of the corners of the lips, operated by tiny muscles known as the depressores anguli oris. This downward curve of the lips is then accompanied by something else going on in the upper area of your face, which Darwin calls a degree of ‘obliquity in the eyebrows’.

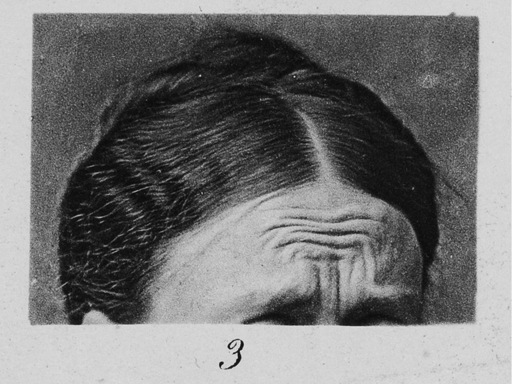

A contraction in the orbiculars, the corrugators and in the pyramidals of your nose raises the inner ends of your eyebrows and draws them together, giving rise to a small ‘lump’. Even the upper part of your eyelids is raised, assuming a pointed triangular shape. Darwin underlined the power of this particular piece of muscular contraction in the overall delineation of a sad expression. In some, but not all people, the most dramatic effect of such muscle contraction is the formation of deep furrows across the forehead which almost look like a horseshoe.

5

Darwin wrote that these muscles might as well have been named the ‘grief-muscles’.

What I find most remarkable about these and all outward physical signs of emotion is their unique, distinctive overall outcome. As we have seen in the preceding chapters, all emotions pervade us with a whole programme of spontaneous bodily changes, facial ones in particular, that come into play as appropriate. It’s not easy to fake sadness. The movement of the muscles arching the inner points of your eyebrows is hard to achieve voluntarily, even for actors.

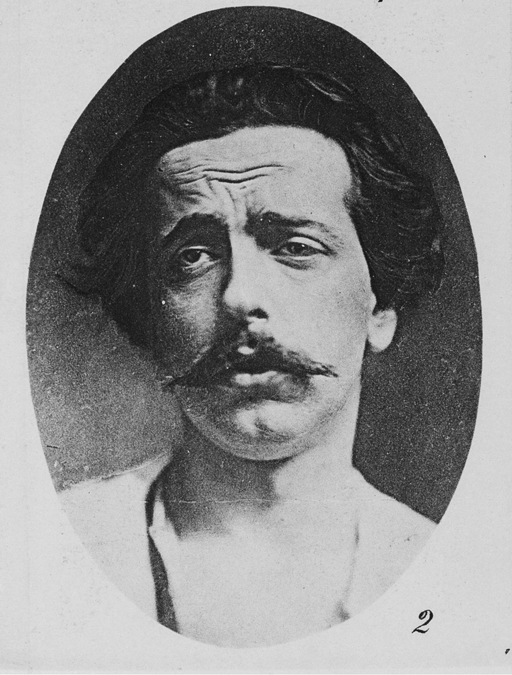

Fig. 10 Pictures of actors simulating grief. Only the man (above) gets the effect on the inner ends of his eyebrows correct. (Wellcome Library, London)

Though skilled at reproducing emotions, even single ones, actors are not infallible at reproducing the singularity of one expression, or all of its components. The man and woman in Fig. 10 are not people in grief, but actors simulating grief, as immortalized by Oscar Rejlander, the Swedish photographer Darwin had hired to illustrate sections of his book. Darwin remarks that in the woman at the bottom of the figure the eyebrows are not engaged exactly as they would be if the sadness were indeed genuine. However, somehow she very successfully acted out the forehead wrinkles. By contrast, the man was better at arching the inner ends of his eyebrows, though not equally on each side.

In sum, it is hard to mimic emotions authentically, especially to an expert eye (I will talk about actors, facial expressions and emotions in more detail in the next chapter). On the other hand, where emotions are genuine they are also difficult to hide.

But something else makes sadness inimitable, and that is the flow of tears.

Cry me an ocean

Wounds and cuts on the skin are cleaned to avoid infection. Emotional lacerations too need rinsing. Sadness and grief are sentiments awash in emotional weeping. Tears are an excess of sensibility, a loosening balm for our feelings.

A few aspects of the physiology of tears are relatively straightforward. As part of their universal function, tears work simply as an effective saline eye lubricant. If eyes couldn’t produce tears, they would be constantly dry and defenceless against external irritants. Lubricant tears are in fact constantly produced and poured on to the surface of our corneas by the lachrymal glands, tiny almond-shaped bulbs located at the inner corner of the eye, close to the nose. To fulfil their protective function, tears also contain lysozyme, which is a natural disinfectant.

But tears are definitely more than salt and an antiseptic when they are shed to bedew our fragile dry ground of sadness – that is, when tears are

emotional

. Despite being a relatively ordinary occurrence, emotional tearing holds exceptional status in evolution as a uniquely human capacity. There is no convincing evidence that any animals cry, even our closest fellow primates the chimpanzees.

Of course it all depends on how you define crying. You can hear juvenile mice, rats or monkeys utter loud, squeaky vocalizations and observe the desperation in their eyes and body movements when they are separated, even for a short time, from their mothers or caregivers. These are clear bold indices of distress. Human babies do that, too. They lament the separation from their mother quite clearly and outspokenly. In all these cases, the crying is the externalization of a protest. But the sad discharge of tears from the eyes in response to loss, or as proof of another kind of emotional shaking, is a feature attributable exclusively to human beings, which even babies learn to do only some months after being born. And this is not just because the lachrymal glands have not developed properly or are not yet functional. Darwin noticed this in his own children. When he accidentally touched with one edge of his coat the eye of one of his children, who was aged just over two months, the child screamed loudly and the touched eye watered, but the other eye stayed dry. Tears started to run properly down the cheeks only when the baby was almost five months old.

6

What is the purpose of crying? Psychologists have wondered for a long time.

In his

Letters from the Black Sea

the Latin poet Ovid wrote: ‘tears at times have all the weight of speech’. Indeed, tears have enormous communicative power. Just as the crying vocalizations shared across various members of the animal kingdom clearly convey a baby’s distress at separation from its mother, emotional tears are for humans efficient expression signals of sadness. The psychologist and neuroscientist Robert Provine, who has researched into several behavioural oddities – things like yawning, coughing and hiccupping – put the communicative power of tears to the test. He has demonstrated that tears unequivocally underscore the emotion of sadness. He and his colleagues showed a group of eighty people several pairs of identical portraits of sad facial expressions. For each pair, one portrait had tears and the other had the tears digitally removed. Without exception the portraits with the tears were ranked sadder than their counterparts with the tears erased.

7

In addition, tears worked to cancel out any ambiguity in facial expression recognition. If you remove tears from portraits of sad faces, the same sad emotional expression is more likely to be misinterpreted and is described as disparately as contemplation, puzzlement or a feeling of awe.

8