Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (26 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

The live performance was a monologue, adapted from a contemporary dramatic poem,

Dionysus the Wild

.

55

The mythological being of the work’s title, half man and half divinity, is the protector of the grape harvest and winemaking and the guardian of mankind’s basic instincts, associated with madness and excess – certainly a figure well acquainted with passions and emotions. But he is, of course, a myth, a fictional character. In the play, he is bizarrely stranded on a New York subway platform in the year 2000 and tells his tumultuous life story, recounting epic travels through cities of ancient times.

The researchers and the theatre team wanted to make the act as close as possible to a real theatre performance and to re-create an environment in which the viewers would feel engaged in the story from start to finish. So, as each of the participants was being prepared to enter the scanner, an actor in the room would begin to recite the monologue. When the scanner bed was made to slide into the magnet, the actor went to act in an adjacent room, but the viewer inside the scanner continued to watch him through prismatic goggles connected to a screen where the scene was being played. When on, a brain scanner emits loud, disturbing noises. To avoid distraction and interference with the appreciation and understanding of the monologue, the researchers and the theatre team cleverly incorporated the noise of the scanner into the performance, by staging it as drones of trains reaching the subway platform where the fiction was supposed to take place.

How did the experiment identify moments of adhesion to the performance?

Prior to the experiment, the theatre director had selected twenty-four ‘events’ within the written text that were intended to elicit a shift in the viewer’s perception of reality, from the actual physical reality (that of the scanner and the experiment room) to the fictional reality of the monologue. These elements worked as adhesion-to-fiction ‘markers’ throughout the play and were highlighted to the actor and the production team as a list of direction instructions that included movements, voice tones and intonations, sound, lighting and other kinds of scenery effects.

A few of these markers corresponded to salient passages in the story of the god’s life that alternated moments of fierce rage and calmer moods, all told and staged very dramatically. For instance, at one point Dionysus recounts his own death. The rhythm of his speech is faster and the tone of his voice more solemn. Later, Dionysus comes back to life. His rebirth is symbolized by the appearance of a light in his hands, which he protects like a precious object. Charged with rage and driven by fury, he takes revenge by killing the men who slaughtered him. During these moments, Dionysus behaves more like a beast and moves quickly, speaks loudly, stares aggressively.

At the end of the scanning procedure, participants were invited to report their subjective experience of the performance while they watched a recording of it made when they were inside the scanner. They were asked to describe their thoughts and feelings about the monologue. Their comments were annotated for every five-second period of the play. After commenting on the whole play, they were also asked questions exploring their involvement in the piece, some of which were specifically intended to probe their adhesion to fiction, e.g. whether or not, and at which specific moment, they were able to disregard the experimental set-up, when they literally felt transported into another reality, or if and when they believed during the play that they were in the presence of Dionysus and not the actor.

This in-depth subjective reporting permitted the identification of moments during the play in which the viewers felt transported into another reality. Since fMRI and heart-rate data were acquired throughout the duration of the play for each of the viewers in the study, it was possible to link any moment of adhesion to fiction to relevant changes in brain activity.

56

For the purposes of the experiment, moments of adhesion to fiction were defined as instances where the spectator’s offline subjective report coincided with one of the stage director’s selected ‘marker’ passages – that were intended to solicit the adhesion – the time-point within the performance matching exactly.

Remarkably, 69 per cent of the elements in the play subjectively experienced as adhesive to fiction coincided with the elements pre-defined by the director. Of these, 40 per cent were textual elements and 60 per cent consisted of more directorial markers, such as the use of lighting or the movements and expression of the actor.

The brain regions that fired in moments when fiction blended with reality were several. One was the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), which comprises the mirror neurons, processes language and is involved in recognizing motion and in the interpretation of facial expression, things that are essential in theatre.

57

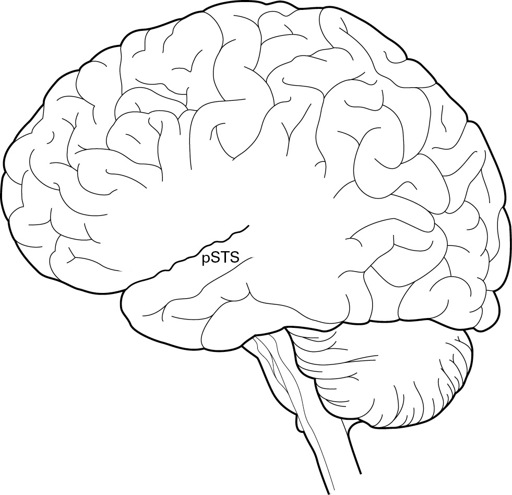

Another was the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) (Fig. 14).

Like the IFG, the pSTS plays a role in our ability to understand other people. Interestingly, when someone sustains damage to the pSTS it becomes difficult for them to accurately assess where another person is gazing or interpret what they are feeling about the object they are gazing at.

58

The pSTS also governs the comprehension of language, including text and verbal processing, specifically the ability to understand metaphor.

59

It would be surprising, therefore, if the pSTS were not active, since watching a play – one rich in text – involves a high degree of language comprehension and the appreciation of a poetic and metaphoric use of language. These same areas have also been shown to be involved in processes of social and aesthetic judgement.

60

Where theatre-watching is concerned, this function probably has a role in aesthetic appreciation of the writing style, the plot or the characters of the play, its overall staging and direction.

Fig. 14 Posterior superior temporal sulcus

Concomitantly, during the adhesion moments there was also a decrease in heart rate and reduced activity in midline cortical areas such as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), which are normally engaged in representation of the self, also in relation to the external world (in chapter 2 I explained that in its function the dmPFC roughly corresponds to Freud’s ego). Absence of activity in these areas would blur the boundary that distances us from the reality of the story being enacted. We are helped to get closer to the fiction.

Such results point to adherence to fiction as being a sort of hypnotic state requiring the spectators’ full absorption into the staged action through temporary loss of self-reference and disconnection from the immediate sensory information – the distinct feeling of being ‘carried away’.

• • •

The fact that we can peer at what is going on in the brain when we watch a play is intriguing. But, however fascinating this research is, it seems to work principally to advance the cause of science. What is in it for theatre? Suppose we reverse the flow and channel the information acquired in the scanner into the process of theatrical composition or performance: we might use the data to identify and reproduce the specific devices of language and staging that have been shown to trigger the highest points of adhesion to fiction, increasing the audience’s immersion in the play.

Would this demand new training for actors? Might directors make more informed choices and develop new approaches that are audience-oriented? What types of movement or expression are most poignant when we try to convey grief, anger or joy? What metaphors work best to compress an action or thought? What elements of plot device, vocal emphasis or even lighting provoke an alteration in the spectator’s brain activity?

While this might sound like an exciting, novel possibility, I remain sceptical that one has to dissect a theatre piece into units and put them to the test of neuroscience and brain imaging in order to ascertain their effectiveness.

So does my friend Ben: ‘I don’t know necessarily what it is that I do that would make an audience laugh or cry, but I know how to do it. It’s a raw instinctive thing that I have been training over the years and that has been honed with skill and technique and craft. In some respects, I don’t think I want to know, because I would be worried that it would become too technical.’

Anyone who has worked in theatre knows that fMRI images and good statistics could never fully substitute for the unpredictable and revelatory power of a rehearsal room.

Writing and acting a theatre scene, or deciding whether it ‘works’ or not, is for the most part a visceral process which, despite being based on technique, craft and experience, maintains a high degree of inexplicable subliminal intuition, which has proved successful for centuries. Theatre artists will continue to exercise their metaphors and explore infinite ways of playing with them as they have in the past. Knowledge of the mechanics of mirror neurons and other brain areas can only add so much to the ability of directors and actors. Perhaps only emotions can generate emotions.

Coda

The lights go down abruptly. Darkness signals the end of the show. A few moments of hesitation, then everyone takes a breath before exploding into a loud choral applause. The lights come up again, blinding Ben’s eyes.

The end of a performance is always a sad moment. Theatre is a ritual of death as much as it is one of birth. The concentration, the involvement in the action, the height of emotion and the intensity of the invisible communication between the audience and the cast across the footlights all gradually vanish. The magic evaporates. I don’t like letting the characters go. I wonder how it must be for the cast to let go of them when a production ends.

There was really no moment during the play when I thought about my brain and what it was doing. When I am moved by an actor on stage, I know that his or her captivating performance is altering my cerebral activity, but the thought of such alteration will neither enhance nor weaken my emotional status.

But I do remember moments when my eyes thinned when I smiled, when I jumped in response to a shout, when my throat began to close when I saw grief. And I remember the moments when I forgot my surroundings.

Peter Brook condenses the magic of theatre into one sentence: ‘In everyday life, “if” is an evasion, in the theatre “if” is the truth.’

61

It’s really about being exalted, about dreaming, falling prey to an illusion. It is about living in constant evasion.

6

Joy: Fragments of Bliss

Nothing is funnier than unhappiness, I grant you that

SAMUEL BECKETT

Count your age by friends, not years

Count your life by smiles, not tears

JOHN LENNON

M

anhattan, five o’clock in the morning. After hours of burning the midnight oil, I finally put the pen down. This time not because I didn’t know how to carry on, but because I was actually done with the writing. I wasn’t abandoning the page with frustration, hoping for a better season. I was finally harvesting the crop.

A source of pleasure for me is to write a poem every now and then. I use verse to condense pieces of my life into short cherishable fragments, ornate strings of words I can easily look back to, repeat to myself and share with others to make sense of changes in the way I look at life. Occasionally, it is a strategy to dress a sore experience in a comfortable disguise – even mishaps assume beauty in poetic form. But in general, it’s just a way to keep my passion for language alive and challenge my skill at transforming emotions into words, mental understanding into written discourse.

My favourite form of poetry is the sonnet and when I landed in New York, a city that infallibly puts me in a good mood, I was right in the middle of creating one. For a week, I had laboured over rendering into this old form of writing the evolution of feelings I entertained for someone. I wasn’t at all sure where our mutual infatuation was leading, but I was sensing some kind of transition, an elevation of some sort: from an insecure ground to a plane of optimism. I could see the emergence of some confidence, the tip of something joyful, and I wanted to celebrate that.

I was determined to finish it, feeling I was close to something, but who can command the creative process? I had worked on the sonnet on the plane – I usually get good ideas when I fly – writing the lines across two pages in my notebook, marking the tonic syllables of each word boldly. I had composed the first eight lines, but the remaining parts of the sonnet were still a chaotic set of ideas that needed to find space to fit into this fixed structure, with rhyme and everything. Anyone attempting to create something knows well that moments of success alternate with moments of frustration. On the page, the broken lines looked like this: