Just 2 Seconds (6 page)

Authors: Gavin de Becker,Thomas A. Taylor,Jeff Marquart

- When the protector is 15 feet from the attacker, there's not much contest; the attacker is likely to prevail.

- At 7 feet, there's a contest; either person could prevail.

- At zero feet (arm's reach), there's no contest --

protectors will almost always prevail.

Each round of the TAD exercise offers different lessons:

Round One (protector positioned 15 feet from attacker) teaches that the five steps it takes to reach the shooter take a lot of time when you're racing against gunfire. Every person who goes through this training develops a lasting respect for those 15 feet.

Round Two (protector 7 feet from attacker) teaches the benefit of being closer. Because most protective details require that each protector observe many bystanders, some distance from bystanders is necessary. The more people one wishes to take in and assess, the farther back from them you must be. Fifteen feet allows a protector to take in many bystanders, which is great -- but the distance limits one's ability to respond quickly enough to any of the people being observed, which is not great. Closer is better, but since we can't afford to assign one protector to every bystander, a middle ground must be chosen -- and 7 feet emerges as that middle ground. At 7 feet, each protector can take in many bystanders and yet still have a viable chance of reaching an attacker in time. Nevertheless, while much better than 15 feet, 7 feet doesn't ensure success.

Round Three (protector positioned directly next to attacker) teaches that when you can position yourself so that the suspect is within your arm's reach, you will prevail virtually every time. Your closeness by itself might deter a suspect from attacking, but even if it doesn't, you'll still likely prevail.

Round Four (protector positioned directly next to attacker, hands pre-positioned) teaches that if your hands are already in position when the attacker tries to present the gun, you actually have less moving to do than he does. It will take you less time to interfere with him than it would take him to do harm.

Photo by Lee Celano/

WireImage.com

Co-author Tom Taylor on protective assignments with hands pre-positioned.

Photo by Lee Celano/

WireImage.com

Note: Gavin de Becker & Associates does not disclose the identity of clients. The public figure in these photos has been named and identified as a client in financial disclosure reports made public by the political campaign as required by law. Subsequently, the information appeared in other public reports.

Experienced protectors often pre-position arms and hands while working a crowd on a protective assignment because at arm's reach with hands pre-positioned,

you've actually started the race before he has.

A suspect who sees he is within arm's reach of an attentive protector whose hands are pre-positioned at the ready, will likely be deterred from attacking. And he is almost certainly prevented from success if he does try an attack. Deterrence persuades a person not to act, but prevention does much more: It works on the mind and the body.

An important note about training: Because it is critical that the experience of prevailing over an attacker is imprinted more often than the experience of failing, we run more rounds with each trainee at 7 feet and at arm's reach than we do at 15 feet.

Overlaying TAD concepts onto real attacks, the success rate for protectors would be even higher than in the exercises. That's not just because TAD attackers are more capable than most actual attackers, but also because TAD grants them some benefits few real attackers get:

- They have the ability to practice -- a lot.

- They are firing at an unobstructed target that cannot move.

- They know the precise location and attention level of protectors.

- In stark contrast to an actual attack, our attackers have relatively little stress because the stakes for them are fairly low.

Given the many conditions that favor the TAD attacker, it's all the more impressive that protectors can win the race some of the time from 15 feet, about half the time from 7 feet, and virtually all the time when within arm's reach.

In TAD, it's reasonable to consider lower-body hits as a partial success because almost all lower body hits occur when the gun is being pushed down by the protector, not when it is on its way up for the initial shot. In other words, protector intervention is responsible for turning potentially lethal upper-body hits into quite survivable lower-body hits.

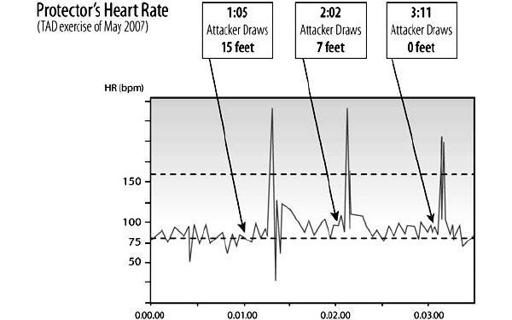

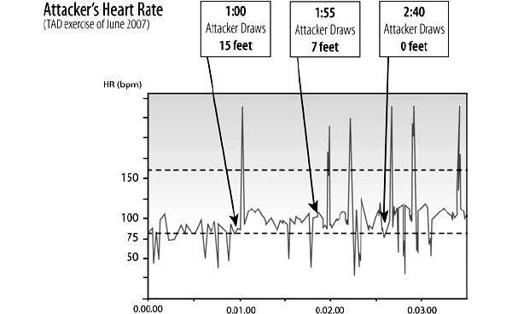

Protector and Attacker Heart-Rates

We've placed heart-rate monitors on TAD students to observe the points at which heart rates spike. With protectors, the big spike occurs at the moment they task their bodies to move very quickly toward the attacker, having seen the attacker draw the gun. No surprises there.

Attackers don't really have to move much at all, so their heart rates remain normal and stable prior to the attack. The heart rates increase as the protector bears down on them, and immediately before the collision. Because it all happens in a second or less, it isn't possible to break down precisely which aspect of the event is causing the attacker's stress and increased heart rate. The main insight gained from monitoring is that attackers are calm pre-attack, and their heart rates do not staircase (climb steadily upward) prior to the attack. Based on interviews with TAD attackers, we glean that the heart rate spike has little to do with their physical actions in the attack (drawing and firing); rather, the spike is associated with muscular tensing, girding the body to resist being pushed over, thoughts of failing, and the general stress caused by time running out as the protector bears down on them. While actual attackers surely have more stress than TAD attackers, what's clear in either instance is this: Having a protector charging toward you has a destabilizing effect on your ability to perform. The teaching here for protectors is that even before the collision, your movement toward the attacker (and calling out "Gun!") is already bringing benefit to your mission. That's because the attacker becomes less and less capable of maintaining accurate aim as his heart rate increases. So, even if a protector is unable to collide with an attacker prior to all shots being fired, the effort itself can still have benefit. For an example, the accuracy of Hinckley's fifth shot was destroyed not by any collision or tackle, but by Hinckley's awareness of and reaction to Dennis McCarthy bearing down on him.

The Physical Power of Information

The charts and statistics from TAD have an inherent power you can harvest right now if you're willing to take this knowledge deep into your cells: Just knowing that you can prevail -- just knowing what the body can do -- enhances what the body can do.

A global example of this truth occurred when Sir Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile. Prior to that, it was widely believed that the four-minute mile was the limit of human possibility, but after Bannister did it, runners all over the world were suddenly able to do it. Just knowing it was possible made it possible -- and you now know that protectors can prevail over attackers.

| Right now and forever, banish the false belief that all attackers have advantages that make them too difficult to defeat. |

TAD has provided an excellent opportunity to assess which strategies are associated with protector success and which are associated with attacker success. Moving out of the small details, we'll now describe specifically how the lessons can be applied in day-to-day protective work, which is better thought of as moment-to-moment protective work.

DATTS (Down And To The Side)

Our studies have shown that the best way to approach and interfere with an attacker who has already drawn a weapon (or is already firing it) is to push the gun arm Down And To The Side (DATTS). There are several reasons:

- Ergonomically, the shooter has less ability to resist a downward push of his shooting arm than an upward push. If you try to push someone's arm up, you have a mechanical and muscular disadvantage, and they are likely to prevail. If you try to push someone's arm downward, you will prevail, even over a much stronger person.

- As the DATTS diagram shows, sideways is the fastest route out of the lethal target zone. But, if you go sideways only, and don't also push down, you might be moving the gun into someone else's lethal target zone.

- You do not want your actions to move the gun upward into position for a head shot that otherwise might not have occurred.

- Your goal is to control both the gun and the attacker, and both tasks are more difficult if the gun is above your head.

- In a crowd situation, a motion of yours coming from below is more likely to encounter interference from the arms and bodies of others.

Though the DATTS acronym helps keep the best approach in mind, anyone who completes TAD training will already have the information firmly embedded in muscle memory.