Kate Berridge (20 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

How plausible is the substantial claim that the public display of this tableau served as the principal reference for David's most famous painting? Some art historians have speculated that the links between the two works are more formal, and that David collaborated with Marie on the composition of her tableau, and instructed her on the exact pose of the body in the bath. Unquestionably the two works

are remarkably similar. The art historian Roger Fry, writing on David's style, refers to âa highly polished Madame Tussaud surface', and there is indeed something waxy about Marat in this painting. In fact the perfect skin is but one aspect of this classically idealized representation of a youthful body that bore no relation to the putrefying green-tinged cadaver of the older Marat that was processed through Paris caked in white make-up in the elaborate funerary celebration orchestrated by David. But an alternative theory is that Curtius and Marie may have copied David's work, and that when his secular pietà was eventually hung in the court of the Louvre its impact was so great that they updated their own earlier Marat ânews story' to emulate his work. Later, in England, the Tussauds were open about copying work by David, specifically his

Coronation of Napoleon

, so this may have been an early example of this practice. Whatever, it is a fascinating chicken-and-egg conundrum, and it is hard to prove or disprove Marie's claims that it was because of the value of her talent as a source for David that she was treated leniently later in the Terror.

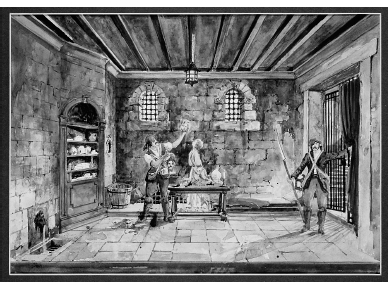

As for Charlotte Corday, Marie claims that she made two portraits of her, one âfrom life' in the Conciergerie prison, and the second after her execution on 17 July, when âthe remains were conveyed to the Madeleine, where Madame Tussaud took a cast from her face.' Marie recalls her prison visit almost in a spirit of admiration for the assassin, whom she found âa most interesting personage'. As well as admiring her physical attributesââbeautiful colour', graceful deportment, clear complexionâshe found her engaging. âShe conversed freely with Madame Tussaud, and even cheerfully, and ever with a countenance of the purest serenity.' If Marie was admitted to see Corday in prison, the visit is not recorded. However, the historical record does include details of her portrait being taken by other artists who had formal sittings with the fetching assassin, who captured the imagination of the public both with her looks and with her self-memorializing. She clearly had a grasp of her allure as a murderer, as is evident in a letter to the Committee of Public Safety in which she requested permission for her portrait to be taken: âJust as one cherishes the image of good citizens, curiosity sometimes seeks out those of great criminals, which serves to perpetrate horror at their crimes.' This would have chimed

with Marie's own views, as it underpinned the voyeuristic appeal of the Caverne des Grand Voleurs and, later, the Chamber of Horrors.

Charlotte Corday's request for a portrait was granted to the painter and draughtsman Pierre-Alexandre Willie. She had spotted another artist, Citizen Hauer, sketching her at her trial, but, although she admired the likeness, the subsequent work by Willie is judged the better. Whether she met Marie is uncertain, but she would no doubt have been gratified by her place in the exhibition, and the praise heaped on her by Marie in early catalogue listings when the exhibition came to England, where Marat's assassin was widely regarded as a heroine.

After the assassination of Marat the political situation deteriorated rapidly. Two weeks later Robespierre was elected to the Committee of Public Safety, a group that combined the role of war cabinet and foreign office. By this time France was at war with most of Europe, and civil war with particularly fierce fighting in the Vendée was a further destabilizing factor. Measures introduced by the Convention became increasingly radical, and citizens found themselves living in a state of hyper-vigilance. A wrong decision by an innocent person could be lethal; even laughing loud or arguing in public was dangerous. After the Law of Suspects was passed in September, the prisons started filling up and the guillotines got busy. On 2 September 1793 Jacques-René Hébert, editor of the inflammatory anti-royalist newspaper Le

Père Duchesne

, announced to the Committee of Public Safety, âI have promised the head of Antoinette. I will go and cut it off myself if there is any delay in giving it to me.' On 16 October his promise was fulfilled, and the Queen was the star billing at the scaffold. Unlike the King, she was not even permitted a closed carriage, but was fully exposed to public humiliation in an open car and without corset, wig and false teethâan emaciated and prematurely aged shadow of her former self.

Marie did not witness her execution, for, as related in her memoirs, âas soon as the dreadful cavalcade came in sight Madame Tussaud fainted and saw no more.' This squeamishness is out of character. It is also at odds with the bizarre legend that she made her way directly to the Madeleine cemetery, where she found the head and body of the Queen lying unattended in the grass, and immediately

made a model. In fact Marie would have had plenty of time to do this, for various versions of the events surrounding the Queen's burial are consistent in maintaining that there was a delay. Unlike the speed and care of her husband's dispatch, there was apparently no hurry to bury her. The time the gravediggers took to get round to it ranges from an unfeasibly long fifteen days to a story that confirms the Continental rule of everything stopping for lunch, which has it that it was during their lunch break that the royal remains were left unattended, giving Marie her chance. Whether a quick hour's handiwork or a more lengthy and leisurely study was involved, the story of Marie modelling in the Madeleine does not stem from the memoirs, but seems to have originated in the London exhibition some time during the nineteenth century. A 1903 catalogue lists the head of Marie Antoinette with the following description: âTaken immediately after her execution by order of the National Assembly of France, by Madame Tussaud's own hands.' Like the death head of the King, that of Marie Antoinette mysteriously appears in 1865. Compared with her appearance in David's tragic sketches, made en route to the guillotine, the wax Queen looks remarkably wellâmore like someone catching up with her beauty sleep than someone recently decapitated.

In contrast there does seem to be evidence that Curtius went to cemeteries to source celebrity heads. In December 1793 Palloy, the âBastille entrepreneur', was greatly impressed by his friend's death head of Madame Du Barry. The popularity of this exhibit was directly related to the hatred of the former mistress of Louis XV. Her howls of fear at the scaffold had distinguished her from other victims, and one can imagine the sans-culottes voyeurs at the waxworks revelling in replaying her performance as they got up close to her head. Palloy was informed that it was such a good likeness because Curtius had been to the cemetery to inspect the real thing. There seems no reason for Curtius to lie to his friend about this. The writer de Favrolles corroborates the account. He relates how Curtius obtained permission to memorialize the features of Madame Du Barry and âexecuted this project in the Madeleine cemetery. You can see this very well-modelled head at his exhibition in the Boulevard du Temple.'

The lack of evidence for Marie's ghoulish pursuits in the Madeleine has not stopped the myths. In the twentieth century a popular tableau in the Chamber of Horrors showed her tiptoeing through the corpses by lantern light, looking for celebrity heads as if she were on a mushroom-picking expedition, but, as with many of her claims, the truth was probably rather different.

Hardship and Heartache

I

N

1794

MARIE

was a woman of thirty-two, but she had already witnessed a spectrum of experience that would have been exceptional in a much longer life. The strictures on commercial entertainment were now even more oppressive than during the

Ancien Régime

. The theatre was in the stranglehold of a patriotic agenda, with censorship every bit as strict as the days of monarchical authority. From 1792 to 1795 the stage was more like a lecture podium than a place of escapism. The propaganda on offer included a disaster-drama-cum-fantasy in which a giant volcano erupted and all the kings of France were lost in the lava, and another box-office hit was a play in which the hero was a husband who grassed on his own wife, who was then sent to the guillotine. As the grip of political correctness tightened, even the business of having fun became deadly serious.

A puppeteer was sent to the guillotine for showing a marionette of Charlotte Corday, and large numbers of actors from the various theatres were imprisoned. One actor from the Comédie-Française called Dazincourt, smarting from the injustice of his incarceration at the Madelonettes, said he could understand why his thespian friends had been locked up, because they had played emperors, marquises, and kings. Yet he had only ever played footmen and valets and poor, simple sans-culottes. But he was lucky: some actors and actresses were beheaded for performing in plays considered anti-republican. In this context most theatres played safe by churning out anodyne patriotic works that could neither enrage nor excite. If the plays were bland, however, the audiences were boisterous. Grace Elliott was unimpressed by the new type of theatregoer: âThe playhouses were filled with none but Jacobins, and the lowest set of common women. The deputies were all in the best boxes, with infamous women in red caps

and dressed as figures of Liberty. In short Paris was a scene of filth and riot.'

Given the restrictions and the increased sense of risk, Curtiusâas ever with an eye for an opportunityâsold some of the dated figures of royals and

Ancien Régime

characters for export. Under a showman called Dominick Laurency, they cropped up in Calcutta and Madras. How the wax was conserved in the Indian climate is unclear, but the touring show was of great interest. The

Madras Courier

of 12 August 1795 announced its opening âin the large commodious airy house and garden of his Highness the Nabob'.

From March until the end of July 1794, under Robespierre's dictatorship, the guillotines in Paris were so busy that Marie relates that there was a perpetual stream of gore running from the Place de la Révolution through the nearby streets. Whereas formerly the papers had printed daily lists of those condemned to death and their crimes, as the victims grew more numerous there was no space for any other details but their names. A wry comment on this was made in one journal, which announced, âToday a miracle has occurred in Paris.

A man died in his own bed.' In the scorching summer, the smell of baked blood was so offensive to residents in the Rue Saint-Honoré that, on the grounds that it was a health hazard, they persuaded the authorities to relocate the guillotine; but it was soon moved back. In the Champs-Elysées toy guillotines were best-selling items, and behind closed doors in select circles the guillotine became a chic accessory. Miniature mahogany guillotines were placed on the table, and ladies took turns to play executioner by placing under the blade doll-shaped bottles whose heads were portraits of the current enemies. The heads were cut off and red liquid flowed from the neck. This lurid liqueur was then poured into glasses, and the assembled guests could toast the victim. There was also a trend for guillotine jewellery. A Dutch-born resident of Paris, in his

Recollections of a Republican

, recalled how âwomen and girls wore golden and silver guillotines in pins and brooches and combs, even in earrings.'

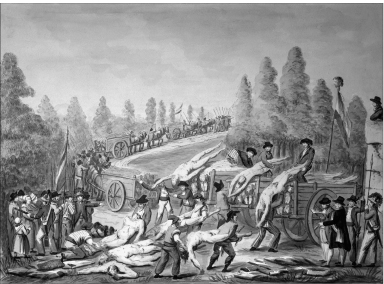

Everyday horrors, carts of corpses became a familiar sight

Further guillotines were installed at the Barrière du Trône and the Place Saint-Antoine. But the prime sight remained the Place de la Révolution, where a restaurant with a particularly good vantage point even put the names of the victims on the menusâthe daily special and a blood-thirsty splat du jour. So blasé had the public become about blood and butchery that it would not put them off their food. A young shop assistant described how they became so inured to the daily horrors that they didn't even bother raising their heads at the tumbrils taking people to the guillotine, or the carts of corpses and baskets of heads that came back. As heads rolled, the famous

tricoteuses

didn't drop a stitch. But indifference angered the authorities, so to intensify the theatre of cruelty they then insisted that victims be driven through the most busy and highly populated parts of the city, with detours through neighbourhoods where they were known. They also took to cranking up the emotional pain by staging executions in such a way that members of the same family would be compelled to witness their relatives being beheaded before them.

Madame Elizabeth, whom Marie always claimed was her erstwhile employee, friend and pupil, met her end in the same way as her hapless relatives, on 27 May 1794. In her memoirs Marie states only how her attempt to preserve Elizabeth's dignity in death was thwarted when âher handkerchief, having dropped, left her bosom exposed to the gaze

of the multitude.' Marie fails to mention whether Elizabeth's head was ever salvaged by Curtius and put into their display.

For the bumper crop of heads included some rich pickings for the waxworks. Marie relates how she was summoned, once again by the Assembly, to make a model of Hébert. In one of her catalogues in Georgian England, she describe the extremist journalist as âfriend of the monster Marat' and a man who was âproductive of much mischief and in many respects resembled the character of Tom Paine'. Hébert was followed in quick succession by Danton and Desmoulins. But in a profession where, then as now, novelty was the life-blood of their business, Marie and Curtius must have been starting to worry that their death heads and a model guillotine were old hat, and could not possibly compete with the thrill of real blood spurting into the front rows of a crowd.

Marie relates how at about this time she herself came perilously close to the block and blade of the guillotine. Her memoirs describe how, denounced as royalists by a grimacer from a neighbouring theatre, she, her mother and a mysterious unnamed aunt (whose antecedents and relation to Marie are never clarified, but who is mentioned several times and was presumably part of the household) received the dreaded knock at the door in the middle of the night and were forcibly removed from their home to La Force, one of the most infamous prisons of the Terror. Their plight was worse for the fact that Curtius was out of the country, and so could not come to their aid: Marie states he was at the Rhine with the army. They found themselves crammed in a cell of twenty or so women, including Joséphine Beauharnais and her young daughter. The future empress of France was apparently a paragon of courage: âMadame Beauharnais did not give way to despondency. On the contrary she did all in her power to infuse life and spirit into her suffering companions, exhorting them to patience and endeavouring to cheer them up.' Just how close to the guillotine Marie came is apparent from her and her cellmates having their hair closely cut every week in preparation for the block. Their turn in the tumbril seemed imminent.

However, the prison episode as remembered by Marie is at odds with other records. In fact Joséphine was never imprisoned in La Force: she was at Les Carmes, a former convent in the Rue de

Vaugirard, having been admitted there on 19 March 1794. Far from being stoic in her captivity, she wept copiously and, according to the account of one of her cellmates, Delphine de Custine, her emotional incontinence made her a total embarrassment. The unisex arrangements at Les Carmes and perhaps the frisson of imminent death resulted in bouts of partner swapping. Joséphine's husband fell madly in lust with Delphine, while Joséphine fell for a general, Lazare Hoche. No mention is made of Marie Grosholtz. Whether Marie was ever at La Force is also hard to confirm. She is not in any official records, but apparently prison officials were often bribed to keep inmates' names out of the records. Given that Collot d'Herbois, reportedly one of Curtius's well-connected friends, was by now even more powerful within the Assembly, it is conceivable that strings could have been pulled if she had had any sort of trouble with the authorities. However, one can't help feeling that Marie's prison claims are yet more strands of her embroidery of the truth, furthering the victim

image that was guaranteed to engage public interest and sympathy in her later career.

Certainly, if Marie was ever incarcerated alongside Joséphine, she was on day release on 8 June 1794 for the Festival of the Supreme Being, for her eyewitness accounts of this event conflict with the dates of her alleged incarceration. It was another of David's great republican extravaganzas and, although no one knew it at the time, it was a spectacularly grand finale. Marie relates how Robespierre rose to the occasion. âHe had decorated himself with peculiar attention. His head was adorned with feathers, and like all the representatives, he held in his hand a bunch of flowers, fruit and ears of corn; his countenance assumed a cheerfulness very foreign to its usual expression.' That day there were an estimated three hundred thousand people processing and singing and making their way to the vast Champ de Mars, where a colossal figure of Hercules, as heroic as papier mâché permits, dominated the arena. Standing on the summit of a vast plaster mountain further elevated by a fifty-foot plinth, Hercules held a tiny figure of Liberty in his hand, like Fay Wray in the grip of King Kong. Marie would have seen the ceremonial burning of a succession of symbolic figures: Atheism, Ambition and finally Egoism. The idea was to reveal one final figure left behind, the inflammable and invincible representation of Wisdom, shining clearly for all to see. But the smuts of Egoism besmirched Wisdom and flecked Robespierre's finery, and with a completely different symbolic meaning the smoke of ego got in his eyes. As Marie relates, these unintentionally comic rather than heroic stage effects âdrew upon Robespierre many sneers'. But six weeks later sneers were replaced by jubilant cheers as Robespierre's tyranny of terror ended with his execution on 28 July 1794.

His dramatic death head, the jaw still bandaged from his suicide attempt, is one of the most gruesomely realistic in the collection. It is this head that Marie refers to many times as having been taken immediately after execution by order of the National Assembly. It is one of the few death heads that she claims to have cradled in her lap. In her memoirs, after relating how Robespierre called her a pretty patriot when he broke her fall at the Bastille, she goes on to say, âHow little did she then think that she should, a few years after, have his severed

head in her lap in order to take a cast from it after his execution.' Elsewhere in the memoirs a second reference is made to her âtaking a cast from his mutilated head'. But she also claims to have made a full-length portrait of him from life at his request, and at his suggestion this was dressed in his own clothes, âto afford additional resemblances'. For maximum effect, in England Marie displayed his death head in isolation. A catalogue for Cambridge in 1818 stated, âThe enemy of the human race we have put by himself as undeserving of a place amongst men.'

On 26 September 1794, Curtius died at his second home, in Ivrysur-Seine. His death is reported in Marie's memoirs, but there is no revelation of her feelings or any details about the last months of his life. Always one for intrigue, she suggests that the circumstances of his death were suspicious, stating that after a post-mortem âit was fully ascertained that his death had been occasioned by poison.' (The official death certificate states natural causes, although it does have alterations and crossings-out.) Curtius is never fleshed out in Marie's memoirs. In what is virtually the only reference she makes to him, she tries to excuse his republican leanings by claiming that he was at heart a royalist, affecting his allegiance to the Revolutionary cause so as to ensure the safety of his household. However, his profile in public life as one of the most successful showmen in Paris and his civic duties mean that he does appear in official records, and from these one can form a character sketch.