Kate Berridge (36 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

It was a successful strategy, and it shows the Tussauds spanning a gap that was becoming more serious in the minds of the moral crusaders on both sides. On the one hand the British Museum had for years showed a stubborn reluctance to admit the general public at all, but when it did it was adamant that it was not going to cater to their comfort. On the other, the moral crusaders had become more evangelical throughout the 1840s in their efforts to suppress the fairs. Unbridled pleasure such as Dickens found at Greenwich Fair and described as âprimitive, unreserved and unstudied' was in his mind part of fairs' appeal. But his view of the fun of the fair was a minority one. Killjoy propaganda escalated at this time. On one poster, the answers to the rhetorical question âWhat harm is there in going to the fair?' leave the reader in no doubt of the moral and physical dangers: âAsk at the workhouseâfairs promote idleness. Ask at the hospitalâfairs are the haunts of vice: vice produces disease. Ask at the penitentiary or any other asylum where poor girls with ruined characters find a shelter from reproach and shame. Ask at the madhouseâdrunkenness is a common vice at the fair. Ask at the prisonâfor fairs lead to felony.'

Marie instilled into her sons the importance of catering not just for the interests of customers, but also for their comfort. Their attention to giving visitors an enjoyable experience helped to cement their

reputation. Cultivating the public's regard in this way may seem obvious, but it was not to the National Gallery, the British Museum, Westminster Abbey and St Paul's. The idea of public relations was anathema to these national institutions. For years, even getting into the Zoological Gardens in Regent's Park meant a rigmarole of advance planning, requiring the backing of a member of the Zoological Society, and people joked that going to see a boa constrictor on a Sunday was almost as difficult as getting a box at the opera. The snooty stance of the learned fellows paved the way for some commercial competition in the form of the resoundingly successful Surrey Zoological Gardens. Here the general public could roam freely in expansive surroundings, and were fed and watered and given plenty of stimulating activity besides the very real pleasure of looking at the animals. Entertainments included regular pyrotechnic displays and such sensational acts as the wonderful Russian air voyagers, performing daredevil aerobatics while strapped on to the sails of a windmill.

The proliferation of these sorts of enterprise was in no small measure due to the obstructive attitude of the previous decade. Sir Humphry Davy had fired a warning shot in a letter to the

Literary Gazette

in 1836 about the woefully inadequate management of the British Museum. He urged a rethink in everything to do with âthis ancient, misapplied and I may almost say useless institution. In every part of the metropolis people are crying out for knowledge, they are searching for her even in corners and byways and such is their desire for her that they are disposed to seize her by illegitimate means if they cannot obtain her by fair and just ones.' Before the word existed, and the concept had been properly grasped, one can see the germination of the market for educational tourism, or infotainment as the trade term it. Marie showed a visionary understanding of the dynamics of mass-market entertainment that continues to keep the exhibition she founded one of the most famous tourist destinations in the world.

Her nineteenth-century rivals were not so enlightened, and class prejudice was rife. The title of an article in the

Literary Gazette

in 1819 exemplified deeply engrained prejudice: âAdmission of the Lower Orders to Public Exhibitions'. Cultural apartheid prevailed until the 1840s, and Marie and her sons may be said to have been enlightened trail-blazers. At one point the National Gallery even proposed that

admission of the public should be contingent upon literacy, with tickets given on proof of visitors' ability to write their nameââIt may safely be affirmed that fine pictures can afford no instruction to those who cannot.' At the British Museum, admission in the pre-reform dark ages was determined by dress, the dress code being, one imagines, a highly subjective interpretation of âdecent appearance'. In a debate about whether to admit the general public on national holidays, one member of the British Museum committee objected that âPeople of a higher grade would hardly wish to come to the museum at the same time with sailors from the dockyards and girls whom they might bring along with them.'

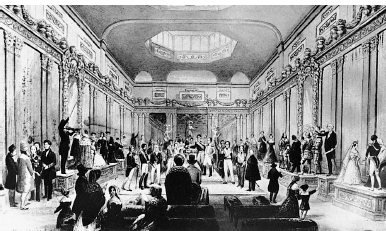

Ottomans, an orchestra, and unrivalled customer comforts, interior, Madame Tussauds

Even post-reform, although it no longer restricted visitor intake to 120 a day, the Museum was almost defiant in the degree to which it refused to consider the comfort of its customers, and it almost prided itself on the lack of facilities. No indoor water closets or refreshments, no browsing without an official guide, an insistence on Latin classificationâall were part of the mantle of obscurity and elitism seen as necessary to protect its assets from philistines. These deficiencies were all absent at Madame Tussaud's exhibition, where an informative catalogue, refreshments, plentiful ottomans to rest on, and background

music all enhanced the visitor's experience and encouraged repeat visits. Although the British Museum was free, visitors felt short-changedâwhich was seldom the case at Tussaud's. She also compared favourably to Westminster Abbey and St Paul's, which came under fire for taking a commercial and exploitative approach to visitors, hustling them around at great speed, and charging fees for all the separate historical sights within. In fact Madame Tussaud was invoked in an article which expressed violent objection to the rip-off that was a trip to St Paul's.

This tariff [twopence admission, but with successive fees throughout a tour adding up considerably] it is manifest has been arranged with a shrewdness that would not discredit Madame Tussaud, nor any other adroit manager of an exhibition, the entire spectacle being distributed into parts none of which affords the visitor too much amusement for his money, whilst each decoys him onward from the previous sight to fresh wonders and expenditure.

To have become a byword for commercialism was a back-handed compliment. But Marie did not really do compliments. When requested to use her considerable talent to restore some of the more decrepit wax figures of historical interest at Westminster Abbey, which many would have regarded as an honour, she was quite huffy. Her great-grandson had it that a favourite family anecdote of their famous forebear was her tart reply when approached by a crusty cleric with this request for renovation: âSir, I have a shop of my own to look after and I do not look after other people's shops.'

In the first half of the 1840s, while the exhibition went from strength to strength, Marie was ambushed by a communication from her seventy-two-year-old husband. Age had not curbed his opportunism, and evidently the phenomenal success of his wife's exhibition in London had filtered back to him. So far as we know she had had no news of him since 1808, and he wrote to Marie using a London-based French colleague, a widow called Madame Castile, as a courier to get the letter to her. His pretext was breathtakingly audacious, given the silence between them, for he wanted to pursue the legitimacy of his claim, as Marie's legal husband, to the inheritance that Curtius had been chasing all that time ago and which had never been resolved. In order to pursue this claim, he needed from Marie a

renewed power of attorney. Madame Castile made it clear that his suit had not been well received: âShe appears to hold against you certain very grave reasons for dissatisfaction since in the first place she seemed not at all pleased to hear from you and told me that she had transferred all her possessions to her sons.'

To say that Marie was not pleased to hear from her husband must have been an understatement, for presumably his approach raised the much more worrying threat of other claims he might make in the future, the most alarming being his potential claim on the profits of the London exhibition. If he had not already thought about this, then he was given an indication of the sheer scale of his wife's success when Madame Castile informed him, âYou can write to her at this very short addressâMadame Tussaud's, as your wife is very well known in London. It is impossible to describe the beauty and richness of this exhibitionâin all my life I have never seen anything more magnificent.'

Joseph and Francisâby now whiskery middle-aged gentlemenârallied to their mother's defence and gave their father short shrift. In a curt reply, they jointly informed him that any further correspondence would be unwelcome, and to deter him from future badgering they asserted their ownership of the exhibition. They were all too aware that if Marie predeceased François (which was fairly likely, given her eight-year seniority to her husband) there would be legitimacy in any claim he made to inherit the London exhibition. To secure their position, Marie resorted to the legal profession she loathed and signed articles of partnership between herself and her two sons.

In December 1844 the family friction is all too evident:

You left mother in debt and difficulty in London, all of which she overcame by hard work and perseverance, without asking from you one sou from your own pocket. Up to the present time you have not sent any money to help her. On the contrary you have sent her no details of her business, and the profits from that business, of which you alone have had the benefits for many years. We believe, with mother, that she has no reason to have any regard for you, who have treated her in such a way. I can assure you that every time you write, mother becomes ill and above all when you write that you will come and see her. It is too ridiculous for words.

But there was no graceful retreat from François: he remained a thorn in the family flesh until his death. Until then, letters continued to cross the Channel with requests and pathetic demands for moneyâall being met with stern refusal.

Anger at François was tempered with filial concern, however, and before his death, in 1848, they relented and loaned him some money. They also visited him in Parisâmuch to Marie's irritation. According to family history, Marie's opposition was so great that Joseph dared not venture into the same room as his father, and satisfied himself with a furtive glimpse of the frail old man from behind a screen. Marie's apron strings were long, but it was also with her purse strings that she attached her two sons.

Behind-the-scenes family feuding did not interrupt the prodigious productivity at the exhibition. In

Lectures on Heroes and Hero Worship

, Thomas Carlyle had in 1841 described history as âbut the biography of great men'. Proving that they were ever attuned to the Zeitgeist, the Tussauds had launched one of their most ambitious historical displays. Topping the bill for Christmas 1845 was the âHouse of Brunswick at one view', a chronological pageant of monarchs and historical figures from George I to William IV, as a sumptuous context for the coronation robes of George IV. Adding a further dimension to the pageantry of the past were the insignia of âThe British orders of the Garter, Bath, Thistle, St Patrick'. While the House of Brunswick boomed, however, the House of Tussaud was feeling the strain, especially the materfamilias.

Her sons' contact with their father had exacerbated Marie's distress at hearing from him again. There was new pain in old wounds. One of the most revealing likenesses of her is a powerful portrait in chalks from this period. Owned now by the National Portrait Gallery, it stands out from other portraits commissioned for public display for its unflinching and unflattering portrayal of an old woman's face. She has a fierce frown. Her mouth is downturned; her cap droops around her ears; her top lip has disappeared like a sulk. It is all downbeat. These are not the glass eyes of Madame Tussaud's wax self-portrait, but expressive eyes. Unlike the bespectacled matriarch at her desk in the famous Paul Fischer work of 1845, this face feels private. This is not a formal composition but an unguarded study, and seems to capture

the vulnerability behind the tough exterior. The beady-eyed money-counter, the brilliant eye of the artist are not here; instead there is disappointment. The eyes convey lack and loss. Interpreted in light of what we know about Marie's life, this single image is a stark reminder that she was a woman who never knew who her father was, a motherless woman who never saw and never mentioned her mother from the moment she left France, a woman who lost a daughter and left

behind an infant son. Most telling is that this portrait is by the man that the abandoned child becameâas a character study of his mother, it is tough matron, not soft mother, and reminds us of the pain behind her professional success, of pain she caused and suffered. Possibly exploited by Curtius, who had relied on her more and more in running the exhibition, she was certainly exploited by her husband and by Philipstal. Her sons' visit to their father who had treated her so shabbily must have felt like disloyalty that was all the more painful for someone unused to loyalty inspired by love. In fact the overarching feeling is that Madame Tussaud, having been deprived of experiences of loving and giving, was probably not very loving or forgiving herself. And she had been soured by exposure to the worst depravity of man, having experienced the slip-slop of human carnage beneath her feet during the Revolution, and in Bristol having witnessed wild-eyed anarchy and arson. Though the work of love seems not to have come easily to her, the impersonal hard graft that led to a long-standing and successful rapport with her public seems to have been different.