Kate Berridge (40 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Increasingly there was a sense of entitlement to access to information about figures in public life. How telling that in the final years of Marie's life Victoria and Albert took legal action in an unprecedented way as a result of infringement of their privacy when family etchings were reproduced without their knowledge for the commercial market. That was a whisper of what would become amplified many times over in the next century, when there would be virtually no escape from the lens and the click that could make a million copies of a private moment. The press that Dickens satirized in

Martin Chuzzlewit

ââHere's this morning's New York Sewer!â¦Here's this morning's New York Stabber! Here's the New York Family Spy! Here's the New York Private Listener!â¦Here's the New York Keyhole Reporter'âwas both a nightmare and a prophesy.

A pertinent comment on our present-day relationship to the stars was made in a book about American cinema by Margaret Thorp, who said, â[The] desire to bring the stars down to earth is one of the trends of the times.' If gods are substituted for stars, then the statement fits Marie's achievement: she helped to bring the gods of her day down to earth. These gods were first of all the royals, and Establishment figures: then they diversified to include entertainers and performers, anticipating current attitudes. Now we don't want merely to bring the stars down to earth, but to wear the same trainers as they do. Some fans treat their bodies as temples to the various stars they revere, eating and drinking the same foods, carrying the same bags. The first stirrings of consumer imitation were happening in Marie's last years.

Her primitive form of virtual reality has entertained without pause for a great many years, and for this alone she deserves far more credit than she has received to date. In so much of what she did can be seen the faint outlines of phenomena that are immense today, and her life remains highly relevant to how we live now, illuminating and reflecting aspects of human nature that are unchanged. In the twenty-first century it is said that if you ask the average teenager

what they want to be the reply is âFamous.' But the craving for renown was evident as early as 1843, an article in the

Edinburgh Review

makes clear:

In short there is no disguising it, the grand principle of modern existence is notoriety; we live and move and have our being in print. What Curran said of Byron, that âhe wept for the press and wiped his eyes with the public,' may now be predicated of everyone who is striving for any sort of distinction. He must not only weep, but eat, drink, walk, talk, hunt, shoot, give parties and travel in the newspapers. The universal inference is that if a man be not known he cannot be worth knowing. In this state of things it is useless to swim against the stream, and folly to differ from our contemporaries; a prudent youth will purchase the last edition of âThe Art of Rising in the World', or âEvery Man his own Fortune-maker', and sedulously practise the main precept it enjoysânever to omit an opportunity of placing your name in printed characters before the world.

But Marie's life also shows us how we have changed. Hers was a labour-intensive as well as artistically complex way of rendering likeness. People enjoyed the results communally, in person. Today ubiquitous camera lenses make instant likenesses for consumption by a global anonymous audience. She lived on the cusp of the coming of photography that Baudelaire felt was sacrilegious, as he witnessed society ârushing as one Narcissus to contemplate its own trivial image in the plate'. Fascination with our own likeness became bound up with changes in the expression and focus of our regard for others. Instead of the solidity of bronze and marble, wax, print and photographs are more fitting media for our more ephemeral allegiances. On two days in 1843, 100,000 people queued to see Nelson's colossal statue when it was on the ground, before it was erected on its giant plinth in Trafalgar Square and that is the biggest difference. Marie's audience still lived in the shade of heroes, whereas we live dazzled by the glare of celebrities, and measure fame in column inches.

Until shortly before she died, in her ninetieth year, Marie was frail but healthy. She had a remarkable constitution. Well into her eighties, she was described as âas hale to appearance as when at the command of the National Convention she took the portraits in wax from the faces of Hébert, Robespierre and the other heroes of the

Reign of Terror which now figure in what she calls her Chamber of Horrors'. As meticulous a housekeeper as she was accountant, she would often personally inspect the linen and lace on the figures to ensure that they were well turned out. She remained, if not a front-of-house presence, an important force backstage, and was certainly party to the proposed expansion of the exhibition in readiness for the Great Exhibition of 1851, for which planning had already begun in earnest. Asthma had been a weakness, but old age was the reason her lungs finally stopped breathing on Monday 15 April 1850. A perfect copperplate hand recorded in the ledger, âMadame Died.'

When she was still a novice with a lot to learn, she had been so excited when in Edinburgh, with the ambitious entry fee of two shillings, she had taken £314

s

on her first day. Advertising then was mainly a matter of handbills. In the week that she died, 800 copies of the catalogue were sold, and takings were £199 9

s

., despite the exhibition being closed on the day of her funeral, the Friday. Advertising now spanned twelve newspapers andâindicative of interest in train touristsârailway guides. Marie's own journey from the Boulevard du Temple to the comfortable surroundings of 58 Baker Street (the address given on her death certificate) had been pretty epic: two countries, hundreds of towns and cities, the drama of near-death, human disappointments. The woman who had arrived with a few packing cases and moulds nearly fifty years earlier, and fretted about her young sons' security, was leaving a priceless collection, a world-famous landmark that meant Messrs Tussaud were set fair for the future.

Beyond her material legacy, prestigious proof of her achievement was evident in numerous obituaries in the national press, including

The Times

, the

Pall Mall Gazette

and the

Illustrated London News

, which also published an engraving. Given the taint of institutional prejudices at this time these were notable laurels. The pages of the

Illustrated London News

tended to be stiff with titled men, people whose family trees had long and royal rootsâ

les vieilles riche

sâand dusty clerics like Reverend Casaubon. That a waxwork proprietor, let alone a woman with a French background and a long history of travelling with a commercial exhibition, and all without a husband, should be included in the pages entitled Eminent Persons Recently Deceased was a substantial form of acknowledgement.

Many tributes, including that in the

Annual Register

, reproduced the biographical details that Marie had always fed her public. But as well as Madame Elizabeth, her class of pupils now included âthe children of Louis and Marie Antoinette'. Apart from this, there were the usual repertoire of

Ancien Régime

and Revolutionary anecdotes, including her imprisonment with Joséphine and, of course, the heads: readers were told how âshe had been employed to cast or model the guillotined heads of those she had known or loved, or those whom she had detested.'

But somehow, notwithstanding all the attention she received, acceptance of her exhibition was never quite there. While money had given her muscle, which she had flexed with serious investments and acquisitions for the business, her mass-market success had mired her for cultural purists. The rising tide of information from print, pictures and travel was for many people a peril. Packaging knowledge into forms that were particularly popular with the expanding middle class had been Madame Tussaud's aim and achievement, but many were dismissive. She still suffers from the snob's sneer. This prejudice is evident in âa visit to Madame Tussaud's' as written for the

Illustrated Family Newspaper

in 1854: âDuring a late sojourn in London, one of my first expeditions was to Madame Tussaud's, a place that everybody sees, or has seen, but which nevertheless it is the fashion in London to laugh at, as being the delight and resort of all the wonder-seeking, horror-loving country bumpkins who visit town.'

Something of the same ambivalence resonates in the initial response to one of the greatest hits for the Tussauds, a painting they commissioned from Sir George Hayter in 1852:

The Duke of Wellington Visiting the Effigy and Personal Relics of Napoleon

. This representation of the greatest living Englishman contemplating up close the greatest dead Frenchman (whom many Victorians thought the greatest man the world has ever seen) was a sensational success. But the

Illustrated London News

qualified its praise:

At first the notion of associating the greatest living man of his age with an exhibition of waxwork may savour of somewhat questionable taste; but when we recollect that it was the only mode by which the two generals, historically connected as they were, could be brought together upon canvas, and when we know that the incident

so embodied was one of actual occurrence, the force of prejudice on this point is weakened.

The longer Madame Tussaud's was around, and the more popular it became, the more the gulf between a worthy gallery visit and fun at Tussaud;s widened in people's minds. Thackeray conveys this succinctly in his novel

The Newcomes

, describing his visitors' reaction to the sights of London: âFor pictures they do not seem to care much; they thought the National Gallery a dreary exhibition, and in the Royal Academy could be got to admire nothing but the picture of âM'collop of M'collop' by our friend of the like name; but Madame Tussaud's interesting exhibition of waxwork they thought to be the most delightful in London.'

But off the pages of novels, in life, Madame Tussaud's left some people cold. The American visitor Benjamin Moran was unimpressed: âSo much for Madam Tussaud's exhibition of wax figures, the resort of the curious, and a sham to please or alarm. It is without misrepresentation, the most abominable abomination in the great city, and the very audience hall of humbugs. Barnum ought to have it.'

It seems more than a little ironic that on Marie's death certificate, dated 18 April 1850, under âOccupation' is stated, âWidow of François Tussaud'. Even in death she was shadowed by a man whose sole contribution to her signified no real giving at all. The funeral took place a few days later at the Roman Catholic chapel at the corner of Cadogan Gardens and Pavilion Road in Chelsea. One imagines plumed horses and a sufficient display of black bombazine and sombre trappings to convey just the right amount of respect, neither too ostentatious nor too frugal to put in question the family's solid middle-class propriety. It is somehow fitting with this maddeningly elusive dynasty that missing from the public domain are any references at all to Marie's passing other than funeral costs. Figures not feelings. Sixty-three pounds, four shillings and sixpence covered mourning dress for staff, six black suits for male staff, four black silk bonnets and six grey straw (âfor domestics'), and an allowance for a cab for servants on the day of the funeralâall being itemised.

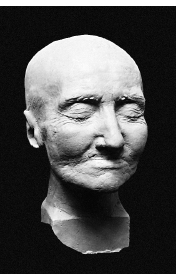

When Marie died, instead of their standard hangman's harvest, it was their mother's sunken features that Joseph and Francis had fixed

in white plaster. The death mask survives. There is also an unobtrusive memorial tablet on the wall of St Mary's Church near Sloane Square, the new Roman Catholic church to which her bones were removed, into a vault, when the old church was demolished: âOf your charity pray for the repose of the soul of Madame Marie Tussaud who departed this life April XV MDCCCL aged XC years, Requiescat in pace. Amen.' But to get beneath the surface to the loves and hates, the foibles and fears of Madame Tussaud is another matter. All we have is fragments of character. But these reveal a strong one. According to a family anecdote told by her grandson Victor, Marie was persistently entreated by a neighbour in Portman Square to come and admire his own valuable art collection. Many people would have indulged an elderly man's pride and even appreciated the opportunity for aesthetic reasons, but Marie is said to have dismissed him by saying that she never visited gentlemen, and when they visited her they always paid a shilling. More telling, she is also said to have rebuked Joseph for his tears when she was on her deathbed, and asked him if he was afraid to see an old woman die. Her aversion to lawyers

was evident in the fact that she left no will, but instructed her sons to share everything. They had, of course, a formal partnership arrangement for the business.

Madame Tussaud's death mask, by her sons

In some ways they were liberated when she died. She had apparently been a hard taskmistress, and, irrespective of the money coming in, practised life-long frugality. Victor Tussaud once wrote to his nephew about the fiscal rules that she insisted the family lived by: