Kate Berridge (38 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

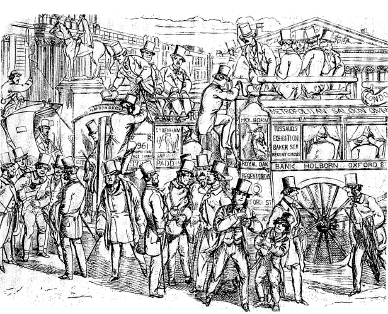

Visitors from the country go to see these waxworks if they go nowhere else; tradesmen living in the neighbourhood put âNear Madame Tussaud's' on their cards; the omnibuses which run down Baker Street announce that they pass that deceased lady's door, as a means of getting customers; and there is scarcely a cab horse in London but would make an instinctive offer to stop as he went by the well known entrance to âTissards' [

sic

].

It was a much-loved institution, so closely identified with London that it defined tourist itineraries. To âdo' London was to visit Madame Tussaud's. A charming story is told of a first-time Russian visitor to Victorian London whose entire stock of English comprised nine words: âSt Paul; Evans, chop, song, supper; Thames Tunnel; Tussaud'. (Evans was a famous music hall, as renowned for robust English food like chops and kidneys as for songs.) Of these attractions, only St Paul's and Madame Tussaud's remain. Madame Tussaud's exhibition had become cultural wallpaper.

Bringing the Gods Down to Earth

M

ARIE DID NOT

merely chart the fame of others: in the final phase of her life she herself attained a new level of recognition in the public arena. Publication of her memoirs, immortalization by Dickens, the commissioning of her portrait by Paul Fischer (whose other subjects included members of the royal family) and a famous Cruikshank cartoon, âI dreamt that I slept at Madame Tussaud's', helped to increase her public stature. References to her on the London stage, songs such as âMadame Tussaud's, or a Row Amongst the Figures', and an almost perpetual presence in the pages of the pressâmost frequently in the new generation of illustrated periodicalsâall paved the path to her becoming a national institution.

She herself was the focus of public interest and increasingly identified with the exhibition, while her large family unobtrusively assumed their place in the wealthy middle class. They dwelt in self-consciously impressive suburban splendour, but lived for their work. Joseph and Francis provided their children with expensive educations in unquestioned preparation for them to join the family business, with the aim of furthering the fortunes of an entrepreneurial dynasty that was already outstandingly successful by the time Marie died. They were upright members of society and supporters of good causesâincluding the temperance movementâand they inspired loyalty in the few employees who were not family members. How proud Marie must have been when in 1847 her sons became naturalized British citizens, with the sponsorship of Admiral Napier, the MP for Marylebone, a distinguished naval officer whose wax figure was on display. This was a ringing endorsement of the family's respectability.

An undated family group in silhouette, made by Joseph, has them standing apart in a formal arrangement, with Elizabeth, his wife, in

the centre playing a harp, as Francis looks on, the tailoring of his frock coat lending him elegance. But it is not him as the paterfamilias figure who is the kingpin of the piece: it is the redoubtable matriarch on the left-hand side, a small well-rounded figure in her trademark bonnet and lace collars, her hand extending an exhibition catalogue to a graceful womanâpossibly her other daughter-in-law, Rebecca. Silhouettes use darkness for definition, and so it is with the family. There is virtually no material that allows us to penetrate their private lives. Even in this picture the background drapery, pedestals and bust of Napoleon suggest the interior of the exhibition; even this is not the family at home. We only ever see them in the outline of their public achievementâespecially Marie, who, approaching her eighties, showed no sign of relinquishing her control of the business.

Before the family photograph album: silhouettes by Joseph Tussaud

Fortunately we have a good eyewitness description of what she looked like in her London years from Joseph Mead, author/publisher of

London Interiors

: âShe possesses a small and delicate person, neat and well-developed features; eyes apparently superior to the use of a pair

of lazy spectacles, which enjoy a graceful sinecure upon her nose's tip. Line upon line, faintly, but clearly drawn, display upon her forehead all the parallels of life. Her manner is easy and self possessed and were she motionless, you would take her to be a waxwork.' Age did not dim her eye for business, and, from improvements and additions to advertising, nothing in the day-to-day running of the exhibition happened without her sanction. Her sprightly manner was remarked on by the

London Saturday Journal

: âThough nearly 80 years of age, being born in 1760 [Marie, whether forgetfully or not, always gave the wrong year for her birth], she does not look more than 65 and bids fair in this respect to rival her maternal ancestors who she tells us were remarkable for their longevity.'

She made a lasting impression on visitors. Enveloped in what one of them called âher veritable black silk cloak and bonnet', bespectacled and sitting from dawn until dusk at the cash desk with a pile of catalogues by her side, she became part of the exhibition, a permanent display. She was the first person whom people encountered when they came to the anteroom at the top of the stairs.

An American visitor whose recollections were published in a memoir,

What I Saw in London

, wrote:

We entered the saloon in Baker Street through a beautiful hall richly adorned with antique casts and modern sculptures, passed up a flight of stairs magnificent with arabesques, artificial flowers and large mirrors and halted at the entrance door to deposit our fee into the hands of the veritable Madame Tussaud herself, who sat in an armchair by the entrance as motionless as one of her own wax figures. It was well worth the shilling just to see her.

Another visitor reported, âHere sat the venerable Madame Tussaud herself, at the receipt of custom. Having paid our shilling she beckoned to a door of a looking glass and on opening it what a sight presented itself. Figures of the size of life, of all ages and of all countries were grouped about the roomâsome of them of such intense resemblance to life as to be quite startling.' Another visitor recalled her âbowing to the company as they came in and out'.

Elsewhere it was her conversation that was remembered, accented in a distinctive Germanic-Gallic mix. She never spoke more than

broken English. Before her memoirs came out, many people commented on the fact that âMadame Tussaud often talked about her life in France.' The stories of her life at Versailles, teaching Madame Elizabeth, her time in the Terror and meeting Napoleon were all trotted out. The claims she made in conversations with visitors to the exhibition percolated into the papers. A

Times

reporter recalled her account of how Curtius and she had been resident in Paris during the horror of the Revolution and, âas the lady herself declares, employed by the authorities of those days to make many of the likenesses now exhibited'.

The London where Marie was nearing the end of her life was frantic with change and unrecognizable from the city she had left to embark on her travels all those years ago. Gaslight and gilding, acres of glass, particularly in the showrooms of shops, all vied to attract consumers. These changes did not go unremarked by the press. In âA Paper on Puffing [i.e. advertising]', an anonymous writer for

Ainsworth's Magazine

of July 1842 asked, âIs the transition from the barber's pole to the revolving bust of the perruquier, nothing?âThe leap from the bare counter-traversed shop to the carpeted and mirrored saloon of trade nothing? Are they not, one and all, practical puffs intended to invest commerce with elegance and to throw a halo round extravagance?'

In

Past and Present

, in 1843, Thomas Carlyle railed against the rise of advertising:

The Hatter in the Strand of London, instead of making better felt-hats than another, mounts a huge lath-and-plaster Hat, seven-feet high, upon wheels; sends a man to drive it through the streets; hoping to be saved

thereby

. He has not attempted to

make

better hats, as he was appointed by the Universe to do, and as with this ingenuity of his he could very probably have done; but his whole industry is turned to persuade us that he has made such. He too knows that the Quack has become God.

As the art of selling became more sophisticated, Victorian advertisers rose to the challenge. The tailors Moses and Sons took copywriting to new heights: âWhen ever I'm in want of dress, I always buy at M&S.' Others took a more literary approach:

To eat or not to eat,

That is the Question.

Whether 'tis better to be unprovided at routs,

Assemblies or pleasure parties,

Or to obtain Hickson's Prepared Anchovies

And have the choicest sandwich.

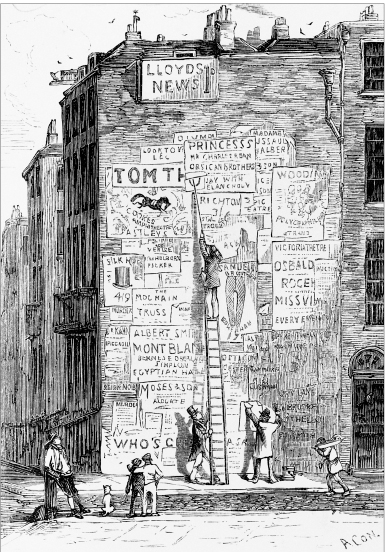

If culverts and cuttings for the railway were disfiguring great chunks of London, other defacements were to be found on walls. Because taxes on newspaper advertising were still prohibitively high, handbills and posters were the preferred medium for those wanting to promote their wares. Advertising mania became a pet topic in

Punch

: âThey are covering all the bridges now with bills and placards. They will be turning the bed of the river next into a series of four-posters.' It was as if Marie was being caught up with, for she had always advertised heavily. Her advertisements were among the first to adorn the sides of London's first mass-transit service, Shillibeer's horse-drawn

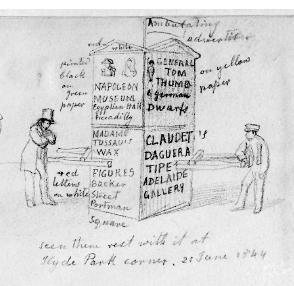

omnibuses, and a sign of her prolific publicity is that in prints of the streets of London from this period you can nearly always discern her name on heavily covered walls. From giant hats and balloon bombardment of flyers to sandwich men and bill-stickers, more attention than ever was being paid to publicity, and London in particular was in the grip of an aggressive advertising boom.

âThe Ambulatory Advertiser', drawing by George Scharf

As Marie was slowing down, life around her seemed to be speeding up. Society seemed to be hurtling towards the future. The accelerated rate of technological innovations affected the mobility of people, things, information and ideas, and all these developments were a catalyst for radical developments in how people enjoyed themselves, and the forms their pleasures took. With the penny post, penny-a-mile travel by third-class rail, and the proliferation of affordable reading matter, there was a growing bank of shared information.

Regional differences began to dwindle, traditional class barriers weakened, and a common cultural frame of reference emergedâsubstantially as a result of the rise of the press, but also influenced by popular fiction, the most influential mass medium of the Victorian age.

Dickens had blazed the trail in this regard. In 1847, writing on Dickens's fame, a contemporary noted, âIt started into a celebrity, which for its extraordinary influence upon social feelings and even political institutions and for the strength of regard and even warm personal attachment by which it has been accompanied all over the world, we believe is without parallel in the history of letters.' Thackeray also enjoyed the fruits of fame, writing to Lady Blessington, âI reel from dinner party to dinner party. I wallow in turtle and swim in claret and shampang [

sic

]'.