Kate Berridge (33 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

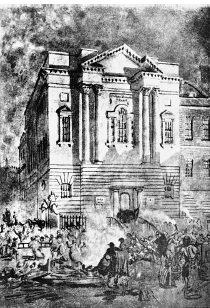

The trouble broke out on the evening of Saturday 29 October, when Sir Charles was at dinner in the Mansion House. Rioters broke in and ran amok, looting the cellars, causing an affray, and then

making off over the rooftops. During the next few days an orgy of looting and destruction ensued, with the administrative buildings of the city as prime targets. The jail was stormed, and many private homes were ransacked and set on fire. Signs of official retaliation were slow to materialize, as fear seemed to paralyse the authorities.

One can all too easily imagine the horrors that particular incidents recalled for Marie: the siege of the local prison; the scaling of the equestrian statue of King William by a man waving a tricolour and shouting for liberty; flaming torches; drunken gangs; the threat and menace of rioters at her door. The past was suddenly storming the present, and her immediate fears were magnified by powerful memories. Marie's ordeal was later reported in the

Bristol Gazette

. As gangs of rioters worked their way along Princes Street, warning residents of their intention to set their premises ablaze, it was clear that the exhibition was in jeopardy. âDuring this awful state of suspense, Madame Tussaud and her family experienced the most painful anxiety. It was stated among other places that the assembly rooms were marked out for destruction containing at that time, their invaluable collection of figures. These, at an imminent risk of injury, were partly removed as hastily as circumstances would permit.' This dramatic salvaging was captured by an eyewitness, the young artist William Muller, whose sketch made on the spot shows the vulnerable wax figures being carried to safety amid lashing flames and a chaos of smoke, water-carriers and people in panic. Marie's lodgings were also affected. As the paper reported, âThe house in which Madame Tussaud lodged on the opposite side of the street was among the number which became ignited from the firing of the West side of the square and we regret to hear that the lady's constitution has received a very severe shock.'

If the wax figures were saved, many humans were less fortunate. There were stomach-churning reports of charred heads without bodies, trunks without limbs, dismembered remains, and entire bodies reduced to cinders being âsuccessively exposed to the public gaze'. Some rioters died horribly slow deaths on the molten-lead roofs of blazing buildings. Although accurate casualty figures were difficult to gauge, apparently when the 11th Infantry Regiment eventually arrived it was ferocious and merciless, sabreing incendiaries to death and mutilating many more.

Charles Kingsley, who was twelve at the time, witnessed the riots from his boarding school on St Michael's Hill, and later likened the sight to Dante's

Inferno

. He was haunted by the noise, the moaning and wailing, and âdull explosions down below mingled with the roar of the mob, and the infernal hiss and crackle of flame'. Press reports of the riots were a shocking compendium of carnage and anarchy that fixed in the minds of the anti-reform movement enduring images of the hellraiser lurking within Everyman. Rather than sympathy for the rioters, there was widespread indignation. Marie upheld the show-business axiom, though her show did not go on in Bristol but moved on to Bath, ten miles away.

The chaos of the aftermath, while looters buried their spoils and the smell of smoke hung heavy, was hardly a conducive time for people to venture out and have fun. But the Tussauds opened in the Masonic Hall in Bath to good reviews, and a semblance of normality helped them to put their traumas behind them. While Bristol burned, in Bath the quadrille band played on.

They stayed in Bath until December, and then in the new year began a slow drift back to London, via Oxford and Reading in 1832, with four months in Brighton in 1833 followed by an extensive tour of Kent encompassing Canterbury, Dover, Maidstone and Rochester. En route they maintained their topicality, responding quickly to the biggest news stories, such as the âassassination attempt' on William IV in the spring of 1833. In reality Dennis Collins was an old sailor fallen on hard times, and the stone he threw at the King was much more of an insult than an injury, but the supposed near-death of the monarch was a good news tag and pretext for airing his likeness.

During their 1833 run in Brighton, another triumph for their publicity was a visit by the King's sister Princess Augusta, along with her nephew Prince George of Cambridge. Writing to Marie via her lady-in-waiting, the Princess conveyed her enjoyment of the show: âLady Mary Taylor is commanded by her Royal Highness the Princess Augusta to acquaint Madame Tussaud with her Royal Highness's approbation of her exhibition, which is well worthy of admiration and the view of which afforded her Royal Highness much amusement and gratification.' After her early days on the road, when she had resorted to embellishing her advertisements with self-generated lists of royal

patrons, Marie must have savoured the unsolicited approval of a member of the royal family. Before she had even reached the capital, in another sense she felt she had arrived.

The year 1833 ended with the exhibition's return to the centre of London, where Marie hired a large room attached to a bazaar in Gray's Inn Road. She lost no time in capitalizing on her royal endorsement: âPatronised by the Princess Augusta and Prince George' was emblazoned on her publicity announcements. Apart from a visit in 1816, when she had set up the exhibition near the West End, in premises that sounded more like the name of a showmanâthe Magnificent MercaturaâMarie had favoured the custom of the provinces to the greater competitive challenges of the capital.

Both London and her exhibition had changed immeasurably in the intervening years. The latter was evolving in size and scope into something more substantial than a travelling show supplying colourful flashes of topicality in improvised surroundings. Display was becoming more sophisticated, with elaborate mirrors, rich costumes and lavish use of gilding, and her sonsâby now in their mid-thirties and established showmenâwere starting to invest in

objets d'art

, paintings and relics. Gradually their exhibition was assuming the character of a museum and gallery, topicality being anchored in history, with material objects lending weight. Some of the early reviews in London reflect this leaning towards learning. âA high intellectual treat' was how one described it; another declared, âWe recommend those who have young persons to take them to see this exhibition, as the view of so many famous characters must make them desirous to open the pages of history.'

Between 1833 and 1835 the radius of travel for the exhibition shortened. Movements within London were interspersed with forays to Blackheath, Camberwell and Hackney, where in 1834 the Mermaid tavern's rooms were filled to overflowing. The local paper proudly reported, âThis is as it should be as it plainly shows that the inhabitants of Hackney can appreciate merit and reward it.' In spite of healthy returns and profitability, the policy of temporary stays determined by attendance figures and takings was relentlessly maintained. Not even Marie's age and the arduous lifestyle prompted them to settle. Even in the spring of 1835, when they hired a particularly

well-proportioned room on the upper floor of a handsome building known as the Bazaar in Baker Street, near Portman Square, they negotiated a short-term lease.

If assembly rooms had provided the perfect milieu for the exhibition in the country, then the bazaars that had proliferated in London since 1816 were similarly suitable. The forerunners of arcades, they mixed retail with recreational facilities, but their chief attraction was as sanctuaries of respectability. They had originated as a philanthropic employment scheme for widows of the Napoleonic wars, who were encouraged to run retail outlets. Character references and strict supervision were all part of creating the right tone. The combination of propriety and a great diversity of hand-made and high-quality merchandise, from haberdashery to household items, was a spur to browsing, and passages were permanently thronged with an affluent, elegant crowd. Catering to a captive audience, recreational attractions were installed in suites of rooms on the same sites. (Before Marie's wax figures, a display of automata had been shown.)

The site chosen by the Tussauds had originally belonged to a regiment of the Royal Life Guards, and from here, in a clatter of hooves and with shiny uniforms and stout resolve, troops had set out to play their part in the Battle of Waterloo. Now the mess room was a pantheon for a wax homage to the heroes of that conflict, and the tableau of the Great Men of the Late War was one of Marie's first installations. While there was no visible sign of the earlier military connections, the equine links were still strong, for the vast ground-floor area still had stabling for 400 horses. There were still occasional horse sales, but when Marie and her family arrived the main trade was in carriages and harnesses, together with the products of the Panklibanon ironworksâa well-known ironmonger's whose range of merchandise included the newly fashionable domestic innovation of a bath (an âabsurd new-fangled dandified folly' in the minds of detractors, who felt that they could manage without water as well as had their ancestors). Rather than a disadvantage, the commercial stature of her neighbours and their extensive advertising was a boon for Marie's own business.

To help register their arrival, the Tussaud brothers deployed considerable monetary and imaginative effort to rig up their new

site. A team of specialists was commissioned to design what was trumpeted to the public as a Golden Corinthian Saloon, at a cost exceeding £1,100, with âwalls hung with the richest crimson velvet; papier-mâché ornaments by Mr Bielefield; gilding by Mr Jennings; the truly superb and unique Imperial crown, sceptre, orb and orders by Mr Bellefontaine; the carpentry by Mr Hine, designed and got up under the direction of Messrs J. and F. Tussaud. The whole of British manufacture, being the only display of the kind and may in all probability be the only one.' The press was impressed: âThere is a profusion of rich drapery, the sides of the apartment are decorated with pilasters with Corinthian capitals gilt in burnished gold and the whole appearance on entering, more especially in the evening when the whole is brilliantly illuminated, is peculiarly imposing and splendid.'

Madame Tussaud and Sons rapidly distinguished themselves as an oasis of civilized calm. The musical accompaniment, which now included a harp, enhanced the viewing pleasure. Successive improvements and additions were enthusiastically reported, and their status received a great boost when they achieved the considerable accolade of visits by some of the most famous dignitaries in the country. Even Marie's inscrutable features must have registered some satisfaction when the

Morning Herald

of 31 August 1835 reported, âHRH the Duke of Sussex has honoured Mrs Tussaud's exhibition at the Bazaar, Baker Street, with a visit on Friday in addition to the Duke of Wellington on Wednesday.' To have this in-person vote of approval (particularly the patronage of the Duke of Wellington) reported by the press trumped Princess Augusta's fanmail by proxy.

âAn Inventive Genius': Mrs Jarley, Madame Tussaud and Charles Dickens

M

ARIE SHOWED NO

sign of slowing down or handing over the reins to her sons. Neither acts of God nor man-made dramas had daunted her. Though savage seas and lashing flames had tested her nerves and threatened to destroy her work, she treated all such events with equanimityâas interruptions to business, but no more. It was never her dwindling stamina that redirected the exhibition.

The eventual decision to commit to permanent premises came at the end of 1836, and was influenced by a celebrity death that proved a particularly valuable business opportunity. The sudden tragic demise of the popular opera singer Maria Malibran, while she was in Manchester, elicited a great wave of sadness. Rather as the wax likeness of Princess Charlotte had served as a focus of public sorrow, in December 1836 the Malibran figure was a mourner's magnet, and people queued to pay their respects to the pretty diva. Family correspondence between Victor Tussaud and Marie's great-grandson John Theodore Tussaud relates the impact of the tragedy, which touched the public all the more because the singer's husband, a famous violinist, was so traumatized that he fled, leaving others to arrange a funeral. âThe sensation created was immense and the newspapers in England and on the continent were full of various accounts and for a time little else was talked about. It was then that your grandfather modelled a most excellent likeness of the cantatrice, I think in the character of Lucia di Lammermoor. The attraction was so great that the rooms were thronged for many months.' The ledgers show that takings doubled during this time, and this perhaps was the spur for Marie and her sons finally to draw their caravans to a halt.

For over thirty years Marie had never allowed herself to be complacent about public interest and, no matter what the laurels and

triumphs, money was always put back into the exhibition. Now a combination of circumstances persuaded them to commit to London. The valuable acquisitions the sons were making (notably Waterloo spoils, including the personal standard and carved eagles of Napoleon) were reason enough to remain in one place. Beyond logistical concerns that made touring less appealing than formerly, proof of the power of public interest that they could generate where they were and recognition from the Establishment both helped them decide that London, and the Baker Street site in particular, represented the perfect conditions for them to thrive. The coming of the railway had made London a very different place from the city in which Marie had arrived from Paris. The hay market at Paddington, once a vital food supply for the horses of the capital, was becoming a distant memory, as the first generation of Victorians associated the same place with the new railway terminus, and the thrill of the locomotive that fed their appetite for travel.

At the age of seventy-five, Marie installed herself as it were over the shop, in an adjoining house that faced Baker Street. Echoing her childhood, she was in a prime position at the very heart of a city pulsating with change and teeming with comfortably well-off customers hungry for her palatable blend of culture and current affairs. The rigours of the road were over and from now on, instead of conveying her wax figures to her customers, she would let carriages, horse-drawn omnibuses and the new trains bring the customers to her.

In the wider social arena as well there were signs of one era coming to a close and another beginning. The youth and girlish vitality of Princess Victoria was in contrast to her aged uncle King William IV, and brought the buzz of novelty to the prospect of her reign. The clearing of land for the railways was so dramatic, in both physical and psychological impact, that Thackeray among others would refer to a demarcation point between the pre-railroad world and the start of a ânew era'. The sound of the navvies at work was like the death knell of the coaching age. By 1836 the rise in newspaper production was a matter of note, and in that year John Stuart Mill wrote about the growing power of an âinstrument that has but lately become universally accessibleâthe newspaper. The newspaper carries the voice of the many home to every individual among them.' In 1836 too the

printer George Baxter perfected the colour printing process that would transform commercial illustration and bring a new pictorial element to the Victorian home. If the Victorians would be the first generation with greater scope to visualize the world around them, at a more profound level their world view also changed. For 1836 was also the year in which Charles Darwin returned from the voyage of the

Beagle

, and the subsequent publication of his findings, twenty-three years later, would shatter the Victorian perception of how the world worked.

But long before the bombshell of evolution precipitated a crisis in theology, advances in geology were chipping away at core beliefs, challenging existing views of time and history. The preoccupation with the composition of the physical world happened in tandem with the realization that social strata were unstable, and that, by either a dynamic or a gradual process, the landscape of society could be radically recast. Marie had not only weathered the violent upheavals of revolution in France, but on tour in England she had lived through the eruptions of Peterloo and the violence of the Bristol riots. During this time she had also witnessed the cumulative quieter build-up of people power. The passage of the Reform Bill marked a time of mounting tension, with democracy challenging the status quo politically, socially and culturally. In her old age in London she would witness a further destabilizing of traditional thought patterns as the growth of scientific inquiry began to challenge traditional religious beliefs.

In 1836 all branches of science were still bound up with religion, and election to the chair of geology at the newly established King's College, London, was in the hands of theologians, including an archbishop, two bishops and a couple of doctors of divinity. Even the Zoological Gardens in Regent's Park were promoted as a place to observe God's purpose. But old certainties were under threat from new interests. Not far from the zoo, Marie's exhibition was a place to see a vision of worldly achievement and a compelling representation of the enticements of renown.

She and her sons were establishing themselves at a time when there was a premium on visual information. A plethora of pictorial entertainmentsâgigantic paintings and endless panoramas and dioramas, which used immense scale and light respectively to produce realistic

representations of battles and other dramatic events from recent historyâenjoyed impressive audiences. Two of the most popular were on Marie's doorstep. At the Colosseum down the road in Regent's Park spectacular panoramas were shown in a building designed by Decimus Burton, and in Park Square East Daguerre's diorama was housed in a building designed by Pugin, where throughout the 1830s what one might term âdisasteramas' were extremely popular, including representations of an avalanche that had buried a Swiss village in 1820 and a fire that had razed a Roman church in 1823. Instead of watching flat screens there was a through-the-looking-glass dimension to how people experienced representations of events. Optical illusion took on a different dimension at the waxworks, where proximity to people rather than drama was the draw, and the public were enthralled. Not that Marie had this market to herself, although none of her rivals posed a real threat. For example, unlike Marie's salon, Dubourg's Saloon of Arts in Great Windmill Street promised to ârepay the visit of that numerous class that hunger and thirst after the horrible' with its âeffigies of giants, dwarfs, murderers, patriots, and pirates', and emulating the Chamber of Horrors was a âselect crypt or den for more than usual villains'.

Marie's rise to national fame coincided with that of the precociously talented young man who did so much to propagate her renown. The publication of

Sketches by Boz

and the simultaneously produced

Pickwick Papers

catapulted Charles Dickens to being one of the most famous figures of the day, In many ways Madame Tussaud and Dickens complement each other. If Dickens enabled people to see the contemporary world afresh via his work, Marie enabled people to learn about the contemporary scene and to feel in the know when they saw her creations. They were both accurate thermometers of public feeling, enabling one to gauge the psychological temperature of their times, to understand people's preoccupations. They were both marketing family entertainment, and in their different media they shared the relatively new phenomenon of cross-class appeal.

Tussaud and Dickens were both self-made and, allying hard work to talent, were immensely productive. They attained a level of recognition for their achievements that was unprecedented: household names at home, their fame rapidly became international and enduring. The

familiarity of their work also seeped into the national consciousness in such a way that each of them came to characterize a particular vision of Englishness that crystallized the topical interests and tastes of their Victorian audience.

The trajectories of their respective rises to fame have more in common than is generally supposed. Published as a part-work between April 1836 and November 1837, the Pickwick series became a publishing phenomenon, rising from 4,000 to 40,000 circulation by part 15. Marie was among those who climbed aboard the bandwagon and, like those plugging Pickwick polkas and chintzes, she capitalized on the opportunities for promotion. Her exhibition soon appeared in the

Pickwick Advertiser

, the advertising leaves that were sewn into each issue.

Towards the end of Pickwick's run, in June 1837, King William IV diedâa king who had not ascended the throne until the age of sixty-four. His death, while mourned, ushered in the promise of youth in the shape of his niece Victoria. In the pages of the

Pickwick Advertiser

, among the notices promoting india-rubber canvases as endorsed by John Constable, the virtues of âKirby's ne plus ultra pins for the hair' were endorsed by the soon-to-be-crowned Princess Victoria. (âWith immovable solid head'âone feels that that is how the nation liked its monarchs as well as its hairgrips.) The new Queen also topped the bill in the advertisement for Madame Tussaud's exhibition: âHer Majesty Queen Victoria the First, Her August Mother the Duchess of Kent, His late Majesty King William IV, the Dowager Queen Adelaide, the King of Hanover, the Duke of Sussex and the Duke of Wellington, with all the leading characters of the dayâthe whole taken from lifeâare now added to Madame Tussaud and Sons' Exhibition.' The name of the mysterious and innocuous-sounding âSecond Room' gave no clue to the darker treats in store for an extra sixpenceâsuch as the heads of murderers, the shirt in which Henry IV was stabbed, and the Revolutionary relics. But their common audience in print is but one facet of the intersection between Madame Tussaud and Charles Dickens.

Dickens happened to shadow the exhibition where he livedâfirst of all when he lived in Furnival's Inn and Doughty Street he was but a stone's throw from the Gray's Inn Road site the Tussauds first rented when they came back to London. Then when he settled in Devonshire Terrace he was on the doorstep of their Baker Street site.

It was here that he wrote

The Old Curiosity Shop

. In this novel the character of Mrs Jarley, the socially ambitious proprietor of a wax-works, is one of his most fully realized portraits of an entertainer. It is also a thinly disguised caricature of his famous neighbour.

Through the output of the ageing Madame Tussaud and the thrusting man of letters we can watch the Georgian era turning into the Victorian one, with a quickening pace and louder volume. We can sense the growth of the mercantile classes made rich by the Industrial Revolution, and can feel a confidence that is almost a swagger as the spirit of Empire fuels patriotism. The anticipation is palpable in the preparations for the coronation of Victoria in 1838. The columns of

The Times

reflect mounting excitement. It became a commercial free for all. There were Royal Victoria pianofortes, coronation medals, facsimiles of the first autograph of Victoria R., and even coronation bonnets. The closer to the day, the greater the number of advertisements offering rooms with views along the route: three windows in Pall Mall were twenty guineas, which made Marie's wax alternative a snip at a shilling. There was an appeal for a Fine Fat Ox weighing not less than 150 stone for a celebratory coronation roast, but the spirit of fatted calf and festivity was apparent in many guises. The Bayswater Hippodrome racecourseâthe poor man's Goodwoodâinvited show-people to take up booths during coronation week, and a large fair at Hyde Park would bring the usual line-up of gingerbread stalls, giants, Punch and Judys, stilt-walkers and waxworks. There was to be a new crown, which

The Times

described as âmuch more tasty [i.e. in good taste] than that of George IV and William IV which has been broken up', and also bigger and better fireworks.

Besides the standard advertisements for her exhibition was the announcement of the publication of Marie's memoirs on 7 May 1838. Over the years she had told visitors âqueer tales' of her time in France, but now, perhaps as part of a ploy to generate more interest in her exhibitionâall publicity for the book stated it was available thereâMarie launched her official biography, containing, as the advertisement in

The Times

stated,

an account of her long residence in the Palace of Versailles with PRINCESS ELIZABETH (sister to Louis the Sixteenth); likewise a

description of the Manners, Etiquette and Costumes adopted at the court of Versailles, and an accurate delineature of the most distinguished personages who formed its brightest ornaments. Also records of conversations in which Madame Tussaud was personally engaged with NAPOLEON, and most of the remarkable characters who figured in the FRENCH REVOLUTION; all of whom were more or less known to her, and with whom she was required to communicate during that eventful period.