Kate Berridge (35 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Dickens gives us enough material to infer what he thought of Madame Tussaud: enterprising certainly, astute for sure, pretentious undoubtedly. There is even a hint of duplicity suggested in his account of how Mrs Jarley recycles certain figures: âMary Queen of Scots, in a dark wig, white shirt collar and male attire, was such a complete image of Lord Byron that the young ladies quite screamed when they saw it.' Yet the overall tone is of wit and warmth rather than waspish character assassination. What Marie and her family made of Dickens's character of Mrs Jarley is another matter. Given their rigorous attention to including the leading figures of the day, his omission from their wax gallery when he was unquestionably the

most talked about and widely influential mass-market author is telling. It was not until his death, in 1870, that the man who in different ways had done so much to publicize the exhibition became an effigy in it. He would never know about the honourâand more to the point, long dead, nor would Marie.

âThe Leading Exhibition in the Metropolis'

I

N THE

1840

S

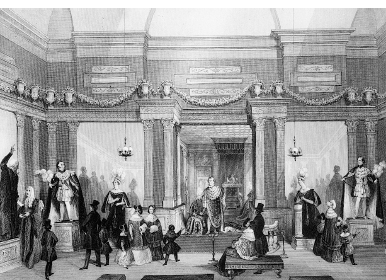

public interest in the royal family was not dissimilar to the avid following of the various part-works that were the nineteenth-century equivalent of soaps, and in which Charles Dickens was the market leader. Madame Tussaud and Sons were quick to capitalize. Queen Victoria's marriage to Prince Albert in 1840 led to a climate of growing affection for the royal couple, and each event in their lives became a popular tableau. Royalty was good for takings. The Queen's face graced a catalogue, her wedding dress of Honiton point lace was copied, and, as a nursery-full of royal progeny came along, cradles with wax princes and princesses were cooed over. Then there were the unscripted dramas of assassination attempts. Advertisements reflect every twist and turn of what would be a long-running storyline, their abbreviated format a succinct summary of royal reportage. âMARRIAGE GROUPâHER MAJESTY, with the Archbishop of Canterbury performing the august ceremony', March 1840. âThe Monster Oxfordâa full-length model (taken from life) representing him in the act of attempting the life of Her Majesty Queen Victoria', 23 July 1840. âThe Prince of Wales and Princess Royal in their splendid cot', 30 May 1842. This was royalty as rallying point for fellow feeling, and the Tussauds developed a type of theme-park patriotism in which they came to excel.

The annual Smithfield cattle show which took place below Madame Tussaud's every December literally beefed up their vision of patriotism. This national event was no mere stroll through a farmyard, but a display of the very best of British livestock from some of the finest estates in the landâEarl Spencer's short-horns, Prince Albert's bulls. It was all about breeding, and the publicity it attracted and the

style of reporting exuded patriotic pride, with an underlying emphasis on the desirability of preserving pedigree, the finest specimens being awarded prestigious prizes. This assertion of the superiority of long lines and skilful husbandry, although referring to animals, correlated with a growing concern in wider society at this time, as an altogether new breed was making its presence felt and causing consternation: the self-made middle classes. The bovine stock downstairs, within smell range of the genteel vision of civility upstairs, was emblematic of separate worlds encroaching on one another. While Madame Tussaud probably didn't much care for the smell of the cattle stall, the dukes and earls certainly found the whiff of new money offensive.

Thackeray coined the present-day usage of the word âsnob' at this time, and in so doing he gave a name to a force that was gathering strength, and which influenced the trajectory of the Tussauds' own success. Snobbery smacks of insecurity, but it is not surprising that the newly wealthy were insecure. With each rung they ascended on the ladder their fear of sliding down increased, and there was also a sense that the ladder was only ever precariously perched against the impenetrable wall of the old order. This insecurity instilled an inferiority complex which powered a quest for acceptance. Self-improvement and material acquisitions were the perceived routes to achieving this, and these were the preoccupations of the vast majority of people who helped Marie and her family to increase their fortune in the 1840s. Her customers were precisely the sort of people Dickens would give life to as the Veneerings in

Our Mutual Friend

, âbran-new people in a bran-new house in a bran-new quarter of town'. In a world where ostensibly many more doors were open, the Establishment would never be âat home' to receive them. They were somehow shut out, no matter how much their money.

By contrast, at the waxworks they were always welcome and would meet people like themselves. More potent still was the way that this gleaming salon encouraged them by supplying proof of the power of individuals to rise in the world through their own efforts. If in classical history a pantheon signified a hallowed space for the worship of immortal gods, then Marie's version operated on a secular rather than a sacred plane, and in the last decade of her life the criteria for

inclusion started to change. The contentsâalways biased in favour of public opinion, not Establishment valuesâreflected an infiltration by men who had made money, singers and showmen. Military heroes could be found in perturbing proximity to assassins and serial killers. Anticipating the exhibition's future format was the prominence of personalities whose success was self-made, and entertainers enjoying commercial success. By the time Marie died, public taste was moving away from bishops to actresses.

Madame Tussaud and Sons was a place that helped one get one's bearings in a society that was in flux. The railways were but one facet of accelerated living that gave a new consciousness of time.

Past and Present

, a highly influential work by Thomas Carlyle, described a split between nostalgia and novelty that was central to the wax-works, as well as being a preoccupation in wider society. The Tussauds' tableaux of the Kings and Queens of England and noble bards were a reassuring interpretation of English history, but other

of their beeswax figures catered to the buzz of novelty, providing brand-new attractions for the likes of the Veneerings.

The Times

described the mix:

Here are monarchs, nobles, ignobles, the pious and impious, the glorious and inglorious, mingled and mixed together in most strange yet not altogether discordant community. There are the Queen, Prince Albert, and the rest of the Royal Family. The predecessors of her Majesty, Kings George I, II, III and IV and King William IVâhere are the Kings of the Stuart line; Oliver Cromwell and the great men of his time; the great, the middle and the little men of modern timesâ¦

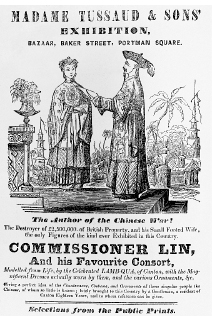

The diverse line-up of contemporaries of interest included some who enjoyed only a relatively short time in the limelight. These included Commissioner Lin and his wife, who came over on a diplomatic visit concerning the Opium Wars and whose elaborate costumes and jewels enthralled their English hosts; Father Matthew, a temperance-movement pioneer; and George Hudson, the railway magnate. As visitors queued, it was less in the spirit of respectful pilgrims, or loyal

subjects, and more as curious fans. Instead of feeling humility before their idols, and awe, they were in many cases looking on them as role models for the power of ambition. But most of all they were simply sight-seeing.

Between 1840 and 1845 Marie, ever astute in gauging what her public wanted, oversaw the restyling of the exhibition with fine art works on a scale that would lend the gravitas of a gallery. Getting away from synthetic pageantry, the Tussauds established themselves as serious collectors, investing in museum-quality pieces of genuine historical interest. Just four words in their ledger, âSet up George IV', describe their largest investment, though the acquisition of his original coronation robes generated a torrent of words from the press. In May 1841 the

Morning Herald

vividly conveyed the splendour of the set:

The liberality of Madame Tussaud has been largely shown in this addition, for she has not only contented herself with costuming the figure in mere mimic apparel, but has actually possessed herselfâand she must have done so at no mean costâof the identical robes worn by that monarch at his coronation festival, robes which cost a generous nation upwards of £18,000! And truly they are vestitures fit for royal shoulders. The figure of the king is exceedingly well modelledâ¦. the effect of the sweeping robes about the figure, the ermine and velvet alternating in large masses, is very striking and combined with the other brilliant furniture of the recess, presents a coup d'Åil not easily to be matched. In addition to the procession robes there are two othersâthe purple and parliamentaryâlying in careless and graceful heaps on a pair of settees, and beside them may be seen superb models of the regalia and of various other insignia of royalty. The walls of the apartment are decorated with sumptuous hangings and a profusion of gilt devices and richly chased tripods support candelabra, which transmit a mellow tinted light over the scene. The general effect is grand and lustrous and embodies to the eye the dreamy impression we have of eastern luxury and magnificence.

But some regarded the way Marie marketed the monarchy as dubious. Dickens for one questioned whether her coronation tableaux did not demean: âIs there not something compromising to the dignity of royalty in the sale of such wares, and their exhibition in this place?' Thackeray was similarly underwhelmed: âMadame Tussaud has got King George's

Coronation robes: is there a man now alive who would kiss the hem of that trumpery?'

Punch

objected to the Tussaud acquisition of important royal portraits. As âpart and parcel of a shilling show' they felt the context degraded the image of royalty to the level of pub-sign vulgarity, showing âno more reverence than the daub of any King's Head that swings and creaks in the doorway of an ale-house'.

Another contentious point was that Marie was not shy about mentioning money: the cost of certain prize exhibits was cited in banner headlines on handbills. To many this confirmed their prejudices that a preoccupation with cost was a proof of her coarseness and inability to gauge the true cultural and esoteric value of an object.

In-house Anglo-French rivalry became more intense in the early 1840s with a concentrated spree of buying Napoleonic relics. A substantial number of these were sourced from the Emperor's brother, Prince Lucien, culminating in the opening of a dedicated room at the exhibition. The memorabilia on show ranged from the mundane, such as the Emperor's underwaistcoat, drawers and Madras handkerchief, to the magnificent, such as a bust by Canova and the Jacobe cradle made for Napoleon's son. Highlighting the difference between a conventional display of

objets d'art

and the human-interest spectacle that Marie knew wowed the crowds, a wax model of Napoleon's infant son copied from a portrait by Gérard was placed in the cradle. The Napoleonic nativity was complete. Reviewers singled out for praise the cloak worn by the Emperor at Marengo and which had served as his shroud, on St Helena. Others were prompted to comment on the relic phenomenon: âBehold little more than twenty years after the wearer's death the cloak of Marengo becomes a curiosity in a show!' And the opportunity was taken for a jibe: âThe first impression of the visitor is how plain and even rude most of the furnishings are, showing how far the French workman of thirty years ago was behind the English one in such matters, as we believe he is still.' Rather than knocking the French, Marie and her sons published some posters in French advertising the Napoleon collection, in a spirit less of entente cordiale than of astute marketing of an attraction that was likely to be of great interest.

The addition of

objets d'art

and relics and the emulation of a museum setting were a calculated move upmarket, helping to assert the Tussauds' authority as leaders of that tier of entertainment that

bridged the gap between the stuffy formality of glass-case culture and the frivolity of the fair. Exemplifying the difference was their prize exhibit in the Napoleon rooms, the coach that had been captured at Waterloo. It was a comeback career for this carriage, which had been so phenomenally successful when William Bullock had taken it on a national tour. Happily it had lost none of its appeal, and Dickens was one of those who took the chance to test-drive it at the Tussauds'. He conveyed the great appeal of climbing into Napoleon's travelling carriage to âplant one's own humble posterior in the seat of greatness'. âIt is a noisy jingling process though, the getting into this conveyanceâand is not done without attracting the attention of everybody in the room; so let all modest and embarrassed persons think twice before they attempt it.' This hands-on element was a key part of the Tussauds' magic, and one of the most striking things about their rooms was how lively they wereâa far cry from the hushed, hands-off culture of dusty and dismal museums, with officious guides making visitors feel small.