Kate Berridge (29 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

From a faded and fragmented paper trail of handbills, exhibition ephemera and provincial newspapers, an impression of Marie's progress can be assembled. Her itinerary encompasses the fashionable resorts of Cheltenham, Bath and Brightonâcities whose fortunes were founded on the leisure industryâand significant trading ports such as Bristol, Portsmouth and Yarmouth. It covers the burgeoning manufacturing conurbations like Birmingham, and the industrial engines of urban growth that were Liverpool and Manchester. Outside London, Manchester was the city to which she returned most often, visiting it six times between 1812 and 1829. But her success was not confined to the smoke-choked industrial north. In Oxford in 1832, as she moved ever closer to London, her exhibition was âvisited by thousands' and, as if describing works at the Villa Borghese rather than wax mannequins,

Jackson's Oxford Journal

enthused about her stylish presentation and the overall impact of her skilful design that combined âbeautiful freshness of painting, bold relief of statuary and the actual effect of dress and ornament united'.

The elements common to the different-sized communities that Marie visited were an affluent middle class and the presence of a local press through which she could communicate with her target audience. Marie was clear about her audience, and it is evident from her publicity that it was the queen bees, not the worker bees, she wanted to attract. âNo improper persons will be admitted' was her cautionary warning in the

Bristol Mercury

in the summer of 1823. Her preferred clientele was that which she evidently attracted in Chelmsford in 1825, when, reviewing her newly opened exhibition there, the local paper reported the attendance of âmuch genteel company'.

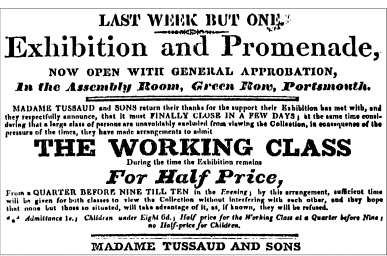

âMadame Tussaud respectfully acquaints the gentry' became the standard opening in her publicity notices that announced the arrival of her exhibition. A notice in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in June 1811 went one rung higher up the social ladder: âMadame Tussaud Artist respectfully informs the nobility and gentry of Newcastle and its vicinity that the Grand Cabinet of Sixty Figures, which was lately exhibited in Edinburgh with universal approbation, is now open for inspection at the White Hart Inn, Old Flesh Market.' She showed almost no interest in wooing the working class. One notable exception is evident on a poster that she had pasted around Portsmouth towards the end of her touring years in 1830:

Considering that a large class of persons are unavoidably excluded from viewing the Collection, in consequence of the pressure of the time, Madame Tussaud and Sons have made arrangements to admit THE WORKING CLASS during the time the exhibition remains for half price, from a quarter before nine till ten in the evening. By this arrangement sufficient time will be given for both classes to view the collection without interfering with each other, and they hope that

none but those so situated will take advantage of it, as if known, they will be refused.

This rare notice hints at a norm of social segregation that is incomprehensible today when mass-market interest is the focus of popular culture. It also betrays a certain cynicism on Marie's part in thinking that the âgentry', so dear to her, would be inclined to pass themselves off as workers and cheat their way into her exhibition like cheapskates. For the workers, even the reduced rate of sixpence was still prohibitive in the context of the standard penny charges at fairs for everything from topical peep shows that were a prized form of news for the illiterate to the unconvincing waxworks that were a staple of the âraree-show' scene.

In the small print of local papers, the growth of the exhibition can also be monitored. The core collection of around thirty figures with which she arrived in 1802 had already doubled by 1805, when the

Waterford Mirror

commended her âsixty capital figures' and âseveral uncommon objects' to âall admirers of real genius and talent'. In 1815, when she was weaving her way around the coast of Cornwall, the

Taunton Courier

and the

Western Advertiser

were advertising her âunrivalled collection of figures as large as life', comprising â83 public characters lately exhibited in Paris, London, Dublin and Edinburgh' and nowâsomething of a comedownâat âMr Knight's Lower Rooms, North Street, Taunton'. By the spring of 1819 the

Norwich Mercury

was alerting the public to their chance to see âNinety Public Characters' at the Large Room in the Angel Inn. In the winter of the same year the

Derby Mercury

referred to âone hundred figures of personages of different periods and nations, illustrious for their rank, talents or virtues; remarkable for their personal appearance, misfortunes or sufferings, or of notorious celebrity for their crimes and vices'.

As the wax figures multiplied, an impressive growth spurt was also evident in the number of illustrious patrons. Whereas before she announced her own exhibition, now on her publicity material there was a fanfare of royal connections preceding her arrival. In Taunton, in 1815, her handbills boast the patronage of âtheir Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of York and Monsieur Comte D'Artois'. In

January 1819 she trumpets the arrival of her collection in Norwich by highlighting the patronage it has received from âhis most Christian majesty Louis XVIII, the late Royal Family of France, their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of York and Her Grace the Duchess of Wellington'. By the spring of 1826, when she opens in the assembly room in Lincoln, she is styling herself as Madame Tussaud, Artist, niece to the celebrated Curtius of Paris, and artiste to her late Royal Highness Madame Elizabeth. (The degree to which she capitalized on her early life in France is evident in a poster from 1816 in which she announces herself as âMadame Tussaud, lately arrived from the Continent', even though, having been in the country for thirteen years, she was hardly packet-ship fresh.) By giving herself an air of social superiority, she adds another dimension of interest to her collection that helps to distinguish her from rival touring waxworks. In fact later on there is legitimacy to her claims of distinguished patrons, but on tour the alleged noble connections and associations that feature in her publicity are all part of the licence with the truth that is the showman's prerogative.

Following the same wheel ruts as Marie's wagons were numerous entertainments whose proprietors similarly puffed up the credentials of their exhibits. The proud presenter of the Scientific Java Sparrows challenged all prejudices about the brain power of birds:

Having finished their education at the University of Oxford, where they met with the greatest approbation from the Vice-Chancellor, the Collegians, and the Mayor and Inhabitants of that learned city, the birds now presented to the particular notice of the nobility and public have required no less than three years to complete their education. They are now perfect in the following seven languages: Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Russian and Spanish.

Often it was the singularity of the size of an animal or human that was the bait to customers. Aged fifteen and allegedly âeight feet around', Miss Holmes, a native of Prescot, Lancashire, was billed as âthe most extraordinary phenomenon of nature, a Gigantic Fat Girl'. Working people and servants could see her for threepence, tradespeople sixpence, and ladies and gentlemen a shilling. Double bills highlighting contrast were also popular. The Devonshire Giant Ox and Tom

Thumb's Fairy Cow were a popular pair, and Miss Hales the Norfolk Giantess went down well alongside the âsmallest person in creation'. Of course, lest punters feel discomfort in gawping at their fellow creatures, a growing trend was to couch voyeurism in terms of educational value. In the case of Miss Hales, her proprietor resorted to verse:

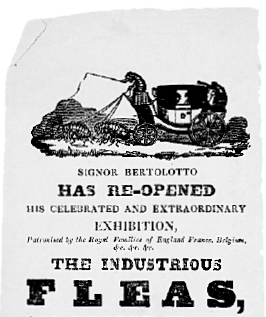

Flea MailâSignor Bertolotto's Flea-drawn Mail Coach

Exhibitions like this may to us be of useâ

What a contrast of creatures this world can produce!

From such wonders eccentric presented to view

We now may our study of Nature pursue.

The smallest performers on the circuit were the those in the flea circuses, whose popularity moved one reviewer to poetry:

No more from our blankets with hop, step and jump

With bloodthirsty purpose you dart on ourâ¦

With other performances now you delight us,

And prove you can do summat better than bite us.

These tiny stars were one of the oldest traditional attractions. Flea-circus purists made a distinction between flea performers that were actually wired together in intricate metal harnesses and those that were an optical illusion.

It is unclear which of these categories Marie's flea circus fell into, but, before her upward mobility meant such frivolities were anathema to her, her fleas had had their fans. The

Worcester Herald

had enjoyed seeing the French imperial coach âpulled by one of those sable-coloured blanket harlequins commonly called fleas'. But her troupe was outclassed by a rival's rendition of âFlea Mailâan accurate representation of England's Pride, her dashing Mail featuring a Flea Coachman who handles his whip in the most approved style and a flea-guard who flourishes his horn.'

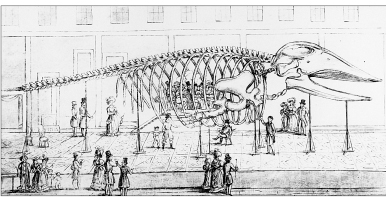

At the other end of the scale was an immensely popular touring show that gave a novel literalness to the concept of a whale of a time. The skeleton of a giant whale was the basis of a hands-on entertainment which packed in people of all ages. It was arranged in such a way as to form a series of carriages, which created an extensive gallery âthrough which hundreds can pass beneath the massive vertebrae and between the giant ribs of this once mighty inhabitant of the Northern deep'. In Liverpool a party of junior Jonahs entered the whale. The local paper marvelled at how many of them could be fitted into the mouth cavity aloneââthe capacious mawâ¦could fit in with ease

one hundred and fifty-two human beings in the shape of tender juveniles of the infant school standing within its mouth at one time.'

This was the richly textured world of popular entertainment that Marie inhabited, and the passing of which Dickens mourned in

The Old Curiosity Shop

. In the time that Marie toured, she was witnessing the twilight years of the traditional travelling shows, and she herself was germinating the new style of recreation for a different generation. The longer she toured, the more her exhibition grew in size and scope, attracting bigger crowds. Her return visits with new material were an important facet of her marketing initiative, which was designed to cement her reputation as a reliable purveyor of educational entertainment, like a public-information service, on what was an increasingly competitive circuit. Impressive attendance figures start to appear in her publicity. For example, in advance of her arrival in Liverpool in the spring of 1821 she states in her publicity that 30,020 people have just visited her in Manchester. In the

Bristol Mercury

of 18 August 1823 the numbers are even more impressive: âHer celebrated collection of figures [was] lately viewed in Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham by upwards of 100,000 people.' In January 1826, her advance publicity before opening in Bury St Edmunds alludes to earlier success on tour by stating that in the cities of Oxford and Cambridge alone 18,000 people had visited her collection.